Dutch Prime Minister, Mark Rutte, recently announced that his country is unlikely to give the green light to the EU Association’s agreement with Ukraine, following an improvised civic campaign against the deal. The Dutch government is faced with a difficult choice between sacrificing a treaty with immense geopolitical significance and defending it to its own political detriment, thus adding more fuel to the Euro-sceptic fire in the country.

The Ukraine-EU Association Agreement is a comprehensive integration instrument that lays the groundwork for a free trade area, visa liberalisation and the gradual harmonisation of laws across a number of areas. Beyond prying open Ukraine’s notoriously fickle trade regime, it also intends to lend crucial support to Ukraine’s efforts in institutional change, including much-needed judicial and anti-corruption reforms, while reasserting Europe’s commitment to Ukraine’s reorientation to the West.

Despite its breadth, the Association Agreement is part of the EU’s longstanding outreach to the east and similar agreements have been signed, in the past, with other post-Soviet states. Some of them, such as the Baltics, have eventually joined the EU. Others, such as Georgia and Moldova, have only recently entered the path of European integration and are currently harmonising their regulatory systems with those of the EU. The agreement with Ukraine has also been applied provisionally, following its ratification by all the EU Member States, including the Netherlands.

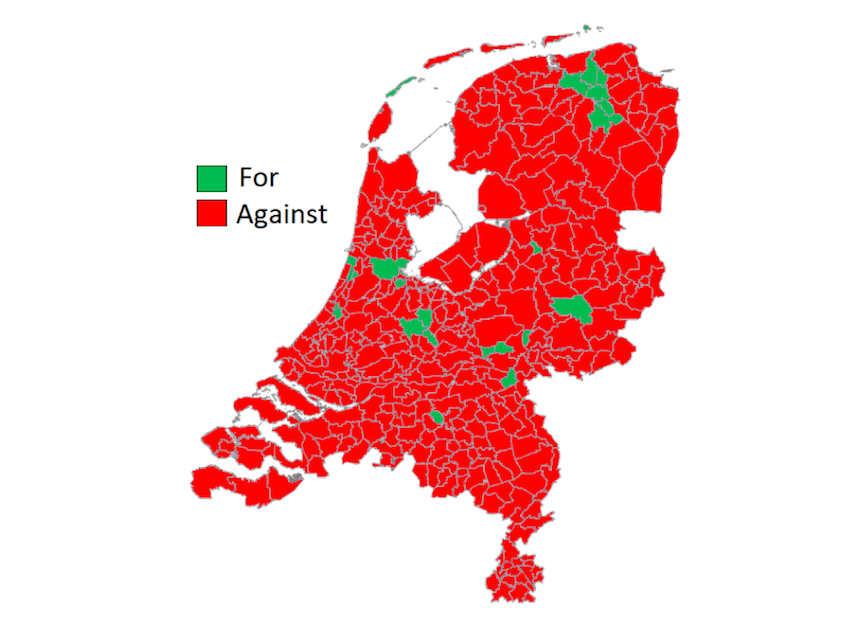

The deal has been unpopular, however, with the Dutch people: revealing that the country is not free from isolationist sentiments. A quickly convoked coalition of civic initiatives, under the name GeenPeil, managed to collect 428,000 signatures: considerably more than the 300,000 required to organise an ex-post non-binding referendum.

In the actual referendum, over 60 per cent of the voters expressed their disagreement with the ratification, while the turnout of 32 per cent meant that the government had to officially reconsider the Act of the Association Agreement. Along the way, the bid for non-ratification became a platform, for GeenPeil and similar movements, to spearhead a civic campaign against the politics of the EU, seen by some as irresponsible and out of sync with national interests.

Although the conservative-liberal Dutch cabinet is aware of the agreement’s significance to the Ukraine and Europe, it also realises that an uncompromising push for ratification might do more harm than good, politically. The Netherlands is preparing for parliamentary elections which should take place in March 2017, and Geert Wilders’s populist Party for Freedom is leading the early polls.

If Mr. Rutte does not want to provide his political and ideological adversaries with extra firepower, he must walk the fine line between defending the agreement and taking heed of the public mood. For the past few months, he has appeared rather under pressure, limiting himself to vague statements about “ongoing negotiations in Brussels”, even as national media were brimming with comments on “the government’s ignorance of the people”. Mr Rutte has now pledged to take a final decision by November.

For the EU, coming on the heels of Brexit in the UK and the continuing drift into populism in Hungary and Poland, the Dutch disagreement is a reminder that no country is immune to Eurosceptic contagion, not even one as stalwarts such as the Netherlands. For Russia, the use of a major EU treaty to express domestic frustration serves as further proof of Europe’s division and vulnerability to external pressures.

However, the stakes are even higher for Ukraine. The Association Agreement is the very same deal that Viktor Yanukovych, Ukraine’s former President, unexpectedly withdrew from, in late 2013. Yanukovych’s defection set the country afire and paved the way for the Euromaidan Revolution, provoking Russian military intervention in southern and eastern Ukraine. In this sense, a European abandonment of the deal, three years later, would be at least as painful symbolically as it would be practically. Undoubtedly, the Dutch prime minister is aware of this fact, but he has to decide whether his own political survival is worth the sacrifice.

_______________

The views expressed in this opinion editorial are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Emerging Europe’s editorial policy.