New research suggests that migration patterns in at least some countries of the Western Balkans are more circular than previously believed.

While the Western Balkans as a whole remains a region that is suffering from the negative impact of external migration, or “brain drain”, a recent study from the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw) reveals that Serbia, Montenegro, and North Macedonia are – at least among the highly-educated – experiencing the reverse: what has been dubbed “brain gain”.

Migration away from the Western Balkans is not new. For both political and economic reasons the region has long been net exporter of people, especially when it comes to the young.

- International trade policy has the opportunity to lead the digital transformation

- Freelancers in Serbia renew protest over status, tax burden

- Are Bosnia and Herzegovina’s borders back on the international agenda?

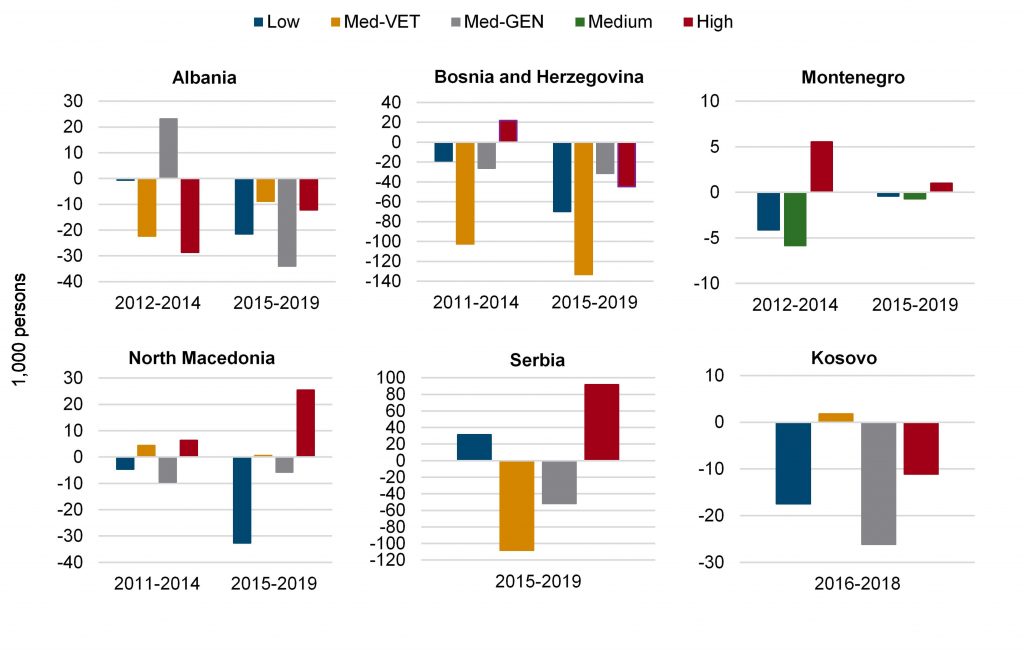

But as the wiiw study reveals, the structure of this emigration is not uniform across all six countries of the region, nor across all education levels.

Unsurprisingly, the study confirms that emigration is highest among young people.

In addition to young people in the region typically having fewer responsibilities and more willingness to engage in the potentially risky move of leaving their home country, they also face some of the highest youth unemployment rates in the world. This is especially true in Bosnia and Herzegovina and in Kosovo, where the current unemployment rates among young people rates are 40.2 per cent and 46.9 per cent respectively. As the wiiw study looked at data from 2011 onward, it should be mentioned that historically the rates have been higher – 2012 saw youth unemployment in Bosnia and Herzegovina at 63.43 per cent.

However, what is somewhat surprising is the breakdown of migration according to education levels. In the region, net emigration happens mainly in the low and medium-educated groups, with Albania being the only outlier – here, net emigration is highest among the well-educated.

Brain drain, the emigration of highly-skilled and educated workers, is high in three of the six Western Balkan countries — Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Kosovo.

It’s especially pronounced in Albania where 40 per cent of the cumulative outflow in the analysed period (2012-2019) were highly-educated people. What’s more, in Albania and Kosovo, brain drain happens primarily with people in the their early to mid-twenties, indicating that many leave as soon as they finish their tertiary education.

Far more interestingly, the other three Western Balkan countries — Serbia, Montenegro, and North Macedonia — have actually recorded “brain gain” in the observed period.

This net immigration is also most pronounced among people in their twenties. In all three countries, emigration of those with medium-level education is highest among the youngest cohort. Therefore, the study authors conclude that the brain gain is the result of people coming back to their home countries after finishing tertiary education abroad.

In the case of Serbia, however, brain gain is also the result of an increasing number of students from surrounding countries who come to attend university in the country. In recent years, Serbia has become a regional hub attracting foreign students.

According to data from the study, between 2015 and 2019, 90,000 highly skilled people moved to Serbia, as well as 30,000 low-skilled workers.

Circular migration

While for the three countries, and especially Serbia, the data pointing to “brain gain” of the highly-skilled is encouraging, the fact remains that all Western Balkan nations are net losers of people. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 665,000 thousand people have left Serbia since 2000.

Youth unemployment remains a one of the biggest challenges for the region — even in Serbia and Montenegro which have the lowest rates, almost a third of those between 15 and 24 that are officially unemployed. High emigration rates among those who don’t belong to the highest skilled groups may point to the fact that people are emigrating just to be able to survive: minimum wages in the Western Balkans remain among the lowest in all of Europe.

Still, the study shows that there is perhaps more circular migration happening in some countries of the region than previously thought.

Overall, however, the policy implications the study authors point out for the region ring true — countries must work on lowering youth unemployment and create quality and fairly paid jobs for the young, many of whom are engaged in temporary work, often in the informal economy.

Those countries who are experiencing brain drain need to make sure there isn’t an oversupply of graduates in some fields and deal with the mismatch between skills attained in universities and the skills that the job market needs.

Those with brain gain should make sure their advantage is put to good use: with policies that guarantee the imported knowledge and know-how actually benefit local economies.

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.

[…] Source link : https://emerging-europe.com/news/brain-drain-in-serbia-montenegro-and-north-macedonia-… Author : Publish date : 2021-04-19 23:00:17 Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source. Tags: 039brainbraindrainemergingEuropegain039MacedoniaMontenegroNorthSerbiasigns Previous Post […]

[…] educated young people have been returning to the former Yugoslav republic on the Adriatic Sea, according to Emerging Europe, a London-based news […]

[…] Brain drain? In Serbia, Montenegro, and North Macedonia there are signs of ‘brain gain’ […]