The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw) has published its new growth forecasts for economies in CESEE up to 2021.

The main conclusion of the report is that the boom experienced by much of the region in 2017-18 is over, and that growth rates will mostly trend lower in the next two-three years. Weaker global growth, US protectionism, Brexit and ongoing problems in the eurozone represent a serious threat to CESEE’s export-reliant economies. Increasingly severe labour shortages are pushing up wages, and this in turn is driving fairly strong private consumption growth. However, this could also threaten external competitiveness and see foreign investors look elsewhere.

“In the short term labour shortages are not necessarily a negative factor – they are behind a lot of the strong wage growth that we are seeing in the region, and therefore driving private consumption growth,” Richard Grieveson, an economist at wiiw told Emerging Europe. “But shortages are getting worse, with more and more firms struggling to find qualified labour to fill open positions, and ever more reporting labour as a constraint on current production. For the big foreign owned firms at the productivity frontier, this is not necessarily a big deal – they can pay the higher wages in the end. But for the rest of the economy, and especially smaller domestically owned firms, this is a real challenge. And even for a lot of the foreign-owned firms in the region, this could affect future expansion plans.”

Growth in much of CESEE is still at or close to its best level since the global financial crisis, reflecting a confluence of highly supportive factors. The fastest-growing economies in the region last year were Poland (5.1 per cent) and Hungary (4.9 per cent), in both cases shrugging off negative political noise. Serbia also had a good year, posting its best growth for a decade (4.4 per cent). By contrast, a sharp slowdown was observed Romania in 2018 (4.2 per cent, down from over seven per cent in 2017), a result of overheating.

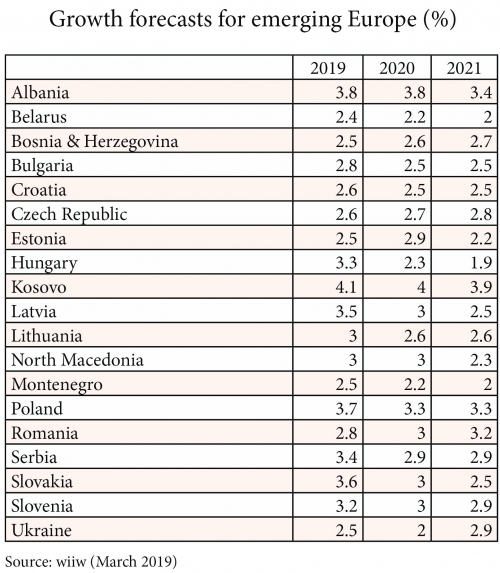

According to wiiw, the fastest-growing economies in emerging Europe in 2019 will be Kosovo (4.1 per cent), Albania and Moldova (both 3.8 per cent), while the slowest will be Belarus (2.4 per cent).

In the long run, wiiw believes that CESEE faces a host of formidable challenges.

Demographic projections indicate a collapse in population that is unprecedented outside times of war and famine. Authoritarianism, state capture and interference in the independence of institutions are all on the rise. Generally low educational standards, levels of network readiness and ICT capabilities (in comparison with Western Europe) could hamstring CESEE’s ability to integrate into a digitalised global economy. The level of automation in almost all countries is well below the frontrunners in Western Europe, North America and Asia.

The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies now believes that policy-makers and firms must act fast to ensure that the region is not condemned to a low- or zero-growth future. First, for a region facing such unprecedented demographic decline and with a high reliance on industrial exports, rapid automation is a priority. Second, governments must strengthen and support the quality and independence of institutions. In EU member states where institutions are under attack, Brussels should play a stronger role in upholding EU standards. Third, higher and better-targeted investment in education and training will be crucial to prepare CESEE for the new digital economy.