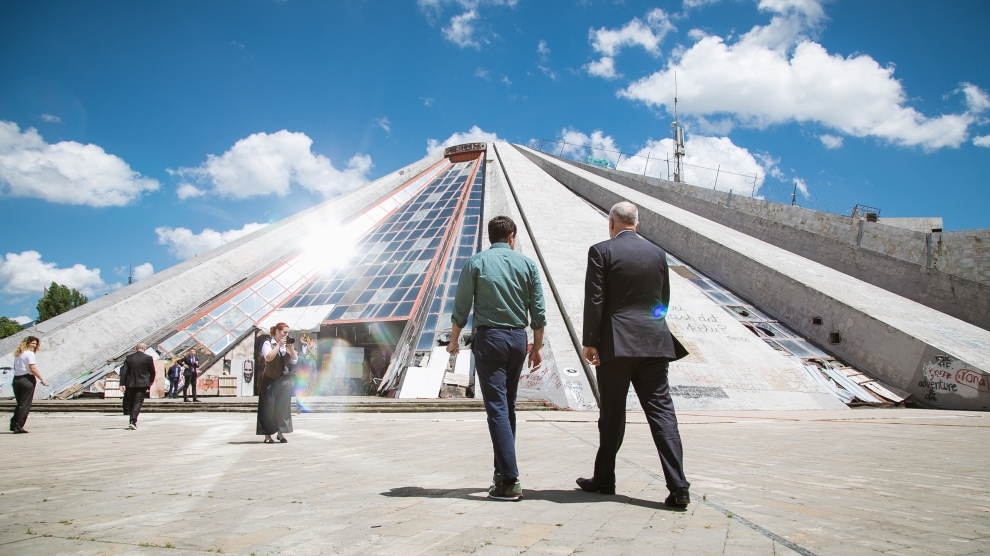

For many years a symbol of the Albanian communist regime, Tirana’s iconic pyramid is stepping into the future. Having served as a museum, a temporary NATO base and a nightclub it is now being transformed into a modern multi-functional centre for technology, culture and art.

The building first opened in 1988 as the Enver Hoxha Museum, a place celebrating the former Albanian communist leader Enver Hoxha, who ruled the country from 1944 until his death in 1985. Mr Hoxha’s daughter, Pranvera Hoxha, and her husband, Klement Kolaneci, were among its architects. And they took liberties which, during the strict communist regime, would have otherwise been unheard of. One of these was the use of what were defined as capitalist materials, imported from the United States to attach marble tiles to the façade. Those tiles were unfortunately removed during the tumultuous period of 1996-97. Originally, the Pyramid was topped by a red star, which has also now been removed.

The museum didn’t last long. In 1991, after the fall of the communists, the Pyramid became a cultural centre, named after Pjeter Arbnori, an Albanian gulag survivor and a victim of the regime. And for a decade, it was Tirana’s most famous nightspot.

During the 1999 conflict in Kosovo, NATO set up a humanitarian headquarters inside the building and in 2001, Albanian television station Top Channel moved in.

Its presence became controversial in 2011 when the monument became the bone of contention between the two main parties of Albania (the Socialists and the Democrats). Former prime minister Sali Berisha wanted to demolish the building, in order to make way for a new parliament.

Civil society opposed the move fiercely. While other countries tore down former communist monuments, the fact that the pyramid had been built relatively recently meant that the majority of people associated the building with Tirana as a city rather than with the communist regime or with Enver Hoxha.

“For many years, the pyramid was a symbol of the city and during the 1990s people used to spend summer in its gardens,” says Klejd Këlliçi, professor at the University of Tirana. “Furthermore, Berisha’s decision to demolish the building seemed authoritarian, which led to reactions and demonstrations to protect the monument.”

“Albania is different from other former communist countries. Those were the years of nostalgia, a wave that current prime minister Edi Rama caught, creating other buildings like the Bunkart, Shtepia and Gjetheve museums. Also, many restaurants and pubs recall the communist period,” he tells Emerging Europe.

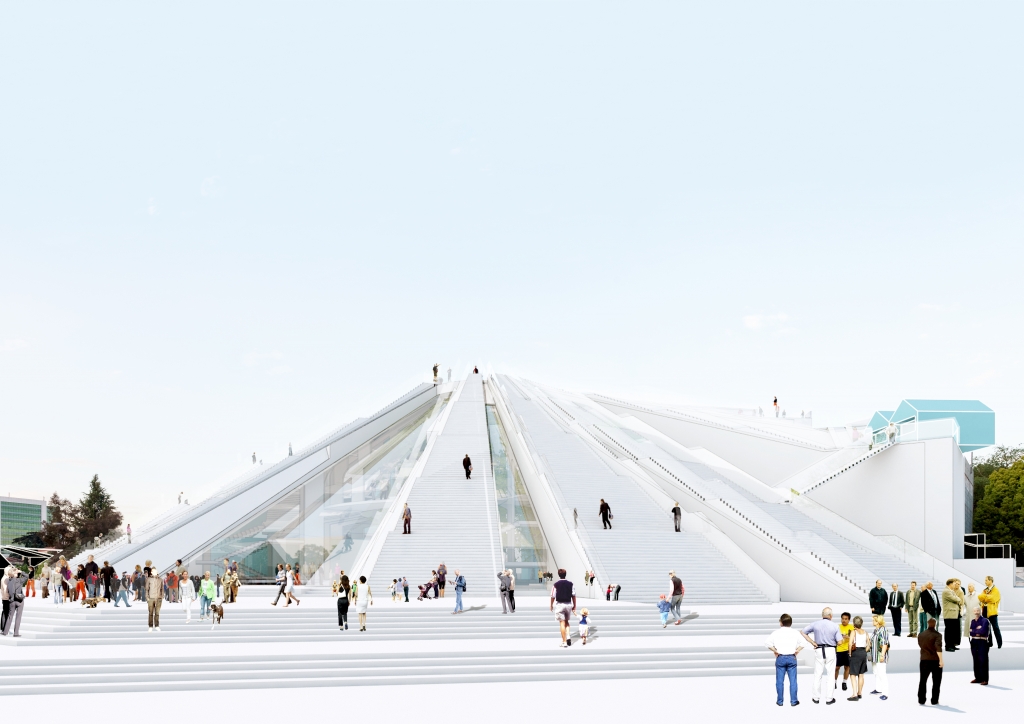

The project belongs now to the Dutch design company MVRDV, which expects to finish the building’s transformation by the end of this year.

According to MVRDV, the project aims to give the building back to the public. The ground floor will be open up on all sides, inviting the public to participate in its diverse educational programmes. By making the façade and roof accessible, the building will also be integrated into the urban fabric affording the public a new perspective of the city. The same logic is applied to the interior, which, through the artful introduction of landscape elements and greenery, is integrating seamlessly with the surrounding square.

“I am not sure there will be any protest against this new project,” Mr Këlliçi adds. “Many of the people that demonstrated to protect the pyramid eight years ago are now working for the government. A government that is affecting a lot the cultural heritage of Tirana. Dozens of villas from 1930-40 are disappearing and the city centre has been completely distorted, with modern tall buildings. Mr Rama, a former mayor of Tirana, even planned to build a skyscraper within the National Museum’s courtyard. I am sure people are susceptible when it comes to the pyramid. They want to preserve it, but also change it, even if many anti-communist intellectuals would still like to see it demolished.”

—

Photos: © MVRDV