Money makes the world go round, and in Central and Eastern Europe – where most countries have yet to adopt euro – there’s huge range of variety in the design of banknotes.

We’ve picked five of the best – contemporary and historical – most of which are likely to be worth far more than their face value at some stage in the future.

Some already are.

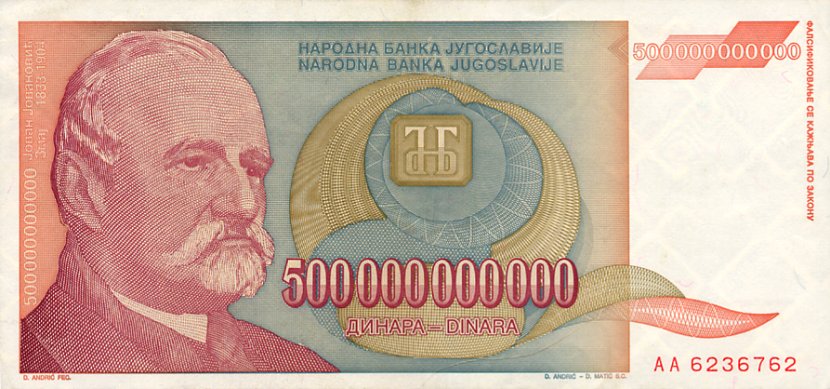

The Serbian 500 billion dinar note

In 1993, Serbia’s economy collapsed due to a combination of the war in the Balkans and accompanying economic sanctions. Its currency began to depreciate rapidly, so rapidly in fact that the dinar-Deutschmark exchange rate was being updated on an hourly basis.

The state responded by printing money, and as it lost more and more of its value, higher denomination banknotes had to be created. This culminated with the now infamous 500 billion dinar note, bearing the likeness of the Serbian poet Jovan Jovanović Zmaj.

Nevertheless, in just a fortnight, as Tim Judah writes in his history of the period The Serbs, the bill lost its value.

Today, you can find it at any souvenir stand around Belgrade, where it goes for around two to four euro: many times over what it was worth when it was in circulation.

Interestingly, this bill, while probably the best known hyperinflation banknote in the region, is does not boast the highest nominal value. That dubious honour goes to the Hungarian 100 million billion (that’s 10 to the power of 21) pengo, printed in 1946 during Hungary’s own period of hyperinflation.

The Macedonian 10 denar note

Most banknotes in Central and Eastern Europe follow a similar symbolic pattern: a worthy person from history on the face, an interesting piece of architecture (in the Western Balkans often a monastery) on the reverse.

But Macedonia decided to break with this pattern for its 10 denar note, first printed in 1996 and then updated in 2018.

Here the face bears an image of the Egyptian goddess Isis and the reverse is a representation of the famous peacock mosaic found in the ancient Macedonian city of Stobi.

Given North Macedonia’s love for all things ancient, the motifs are not surprising. At the very least, they’re a welcome break from tradition.

The Czech 500 koruna

Women are in the minority globally when it comes to being featured on money. In the countries of the EU that still haven’t switched to the euro, at least five – Bulgaria, Croatia, Romania, Hungary, and Poland – don’t have any standard notes featuring women in circulation.

Bulgaria did, briefly, on the 20 lev note feature Desislava Sebastokrator, a 13th century noble and patron of the Boyana Church in Sofia. But in a 1999 currency reform she was replaced by the poet and revolutionary Stefan Stambolov. Poland has also in the past featured women, Dobroawa of Bohemia and Marie Curie, on commemorative issues of the 20 złoty note.

When looking at the bills currently in circulation, Czechia does better than most: it has not one but two women gracing the face of its banknotes.

We are choosing the 500 koruna bill, featuring the writer Božena Némcová.

Némcová was an important literary figure in the Czech National Revival movement of the 19th century, penning the influential novel The Grandmother.

The Romanian 2,000 lei commemorative note

Another banknote breaking with tradition, this time in commemoration of the 1999 total solar eclipse that was visible from much of Eastern Europe. The eclipse itself had whipped Europe into a frenzy with many going out into the streets armed with special goggles to observe the once in a lifetime phenomenon.

The Romanian National Bank commemorated the event with this 2,000 lei note, featuring an eclipse chart on the face and a stylised map of the eclipse’s track over Romania. It was also the first polymer note in Romania’s history (today, all the country’s banknotes are polymer).

Following a currency reform of 2005, the note is no longer in circulation but remains a lovely way to commemorate this cosmic event. And you too can have one, as the note sells for around three US dollars on E-bay.

The Bulgarian 20 lev commemorative note

In recent years, many countries have decided to update their notes to more modern designs. Euros are one such example, with their shiny and bold designs, while the most recent redesign of the Swiss franc is emblematic of this shift. It features a fetching and ultramodern vertical design with bold primary colours.

But most countries in Central and Eastern Europe are keeping it traditional. Bulgarian lev notes still look much the same as they did 50 years ago.

This 20 leva commemorative polymer note, issued in 2005, highlights the best of this traditional style into one single bill. The washed out colours, the architectural drawing style lines, the focus on statues and old buildings. It’s all here, and it’s all quite old fashioned: indeed, the back of the banknote features a replica of the first Bulgarian 20 leva note, issued in 1885.

And that’s exactly why it’s so fascinating, and one of the more valuable on this list: it sells for around 25 euros.

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.