The School of Slavonic and East European Studies, or SSEES as it is commonly known, is a research and education institution focused on the central and eastern European region. Part of University College London (UCL) since 1999, its history stretches far deeper, and the school retains its original aims of spreading knowledge and understanding about a region that is all too often misunderstood.

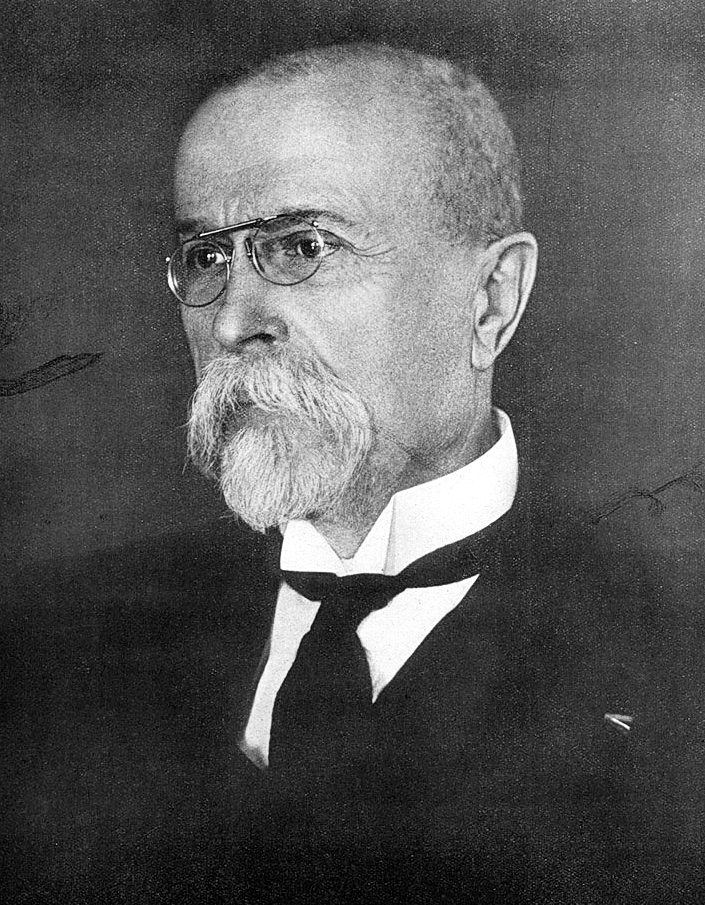

The school was founded in the midst of World War I by statesman Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, who shortly afterwards would be one of the founding fathers of Czechoslovakia, and become the country’s first president. As Dr Tomáš Cvrček, a professor at the school, tells Emerging Europe, “it’s important how institutions are founded for their later development, it’s where you set the DNA.” Masaryk was a defining example.

The future Czechoslovak president had an American wife, Charlotte Garrigue, and during the war circumnavigated the globe. On his return from a meeting with Woodrow Wilson in Chicago, Masaryk stopped over in London to found SSEES, along with a group of scholars studying the region, such as Robert Seton-Watson and Bernard Pares.

This was a stepping stone in Masaryk’s efforts to steer scholarship about the region away from the then German-centric discourse. Instead, he wanted to establish contacts with the western powers of Britain and France. Of course, this fitted in well with the British agenda at the time, which was more than ready to have intelligence on a region far from the filter of German scholarship.

After Masaryk became Czechoslovak president, the school aimed to keep his legacy alive; the notion of developing understanding rather than adhering to hegemony. “The way to deal with bias is to diversify the methodologies and to then extract something from underneath, something that is leftover once all the bias is subtracted,” says Dr Cvrček.

During the 20th century, the school’s speciality made it the subject of a number of key interests. In the 1930s, SSEES was granted funds from some of the region’s governments, including Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Romania. During the Cold War, the UK government seeded positions that were recognised as supporting national priorities. Since then, the school has distanced itself from offering language courses for UK diplomats, now mixing these with social sciences, cultural studies, and humanities.

These days, the school aims to remain faithful to its Masaryk-inspired roots, particularly in honouring his international flair. As the school’s director, Professor Diane Koenker tells Emerging Europe, a third of the school’s students are from the UK, a third European, and a third international. It is this vibrancy that, according to the school’s professors, makes SSEES so unique.

“At SSEES you can find people like myself who are from the Czech Republic, or who are from Poland or Romania, they are ex-pats, but at the same time you will find people from America or England who have an outsider interest,” explains Dr Cvrček. “This mixture is part of what makes SSEES work. You have people who have a stake in the region, and people who are looking at it from a distance.”

This allows the school to at least partly rid itself of unspoken assumptions. However, while diversity in academia does aid in counteracting a cultural filter of bias, it is impossible to cancel it out entirely. Nevertheless, the school aims to produce and aid graduates who understand the importance of the region interdependent of objectivity. “Since coming to SSEES, my perspectives on the region have altered and been challenged a thousand times and from multiple angles,” explains Giulia Guerrini an undergraduate specialising in economics.

Other students feel as if the region has been overlooked entirely by their home country.

“Coming from Australia, people often view my choice to specialise in the region as irrelevant,” says Isabella Ross, a politics and sociology undergraduate. “People are often shocked to discover that not all of the region is democratic, for example, and fail to understand this significance within the broader global context.”

According to Professor Koenker, the school aims to build on the foundations of the grounding methodologies of politics, economics and history that then allows students to pursue both disciplinary and interdisciplinary studies backed by training in languages and culture. “We can see the value of this kind of research and education in the trajectories of SSEES graduates, who have moved on to careers in government, security, media, academia, and business, and in the close relationship with government and nongovernment organisations to provide briefings and insight into our part of the world today.”

The region will always remain relevant, producing new challenges as one chapter closes and another opens, and schools like SSEES will always have a place in academia and beyond.

“Throughout SSEES’s history, the geographical focus has stayed the same, but the region always comes up with enough new things happening creating a new demand for expertise,” says Dr Cvrček. And now, he explains, with the resurgence of nationalism and social conservatism, along with a divided stance over the future of the European Union, research about the region is as important as ever.

Masaryk’s bust symbolically keeps watch over the school’s library. As long as he is there, SSEES will continue to preserve his agenda of peace through knowledge and understanding alive and well.

—

Top photo: UCL/SSEES

—

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.

[…] the help of émigré intellectuals and politicians such as the Czech Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk and the Slovak Milan Rastislav Štefánik, they grew into a force of over 100,000 strong. They […]