In a somewhat surprising move, the European Council did not agree to give the green light for the official opening of accession talks to Albania in 2019. That was unexpected, because the European Commission and most of EU countries recognised the progress of reforms in the country and supported an opening of – usually lengthy – negotiations.

Officially, France asked for a reform of the complete EU enlargement process, before the European Council should take any further concrete decision in the case of Albania or North Macedonia. However, some other countries – such as the Netherlands and Denmark – were also a bit sceptical of Albania’s progress on the path of reforms. In any case, a more cautious line was discernible regarding Albania than for North Macedonia. Nevertheless, Germany was in favour of opening negotiations, but only after Albania has fulfilled a long and stringent list of conditions, including the reformation of the constitutional court, the high court, electoral reform, the establishment of an investigation bureau and anti-corruption structures, amongst much else.

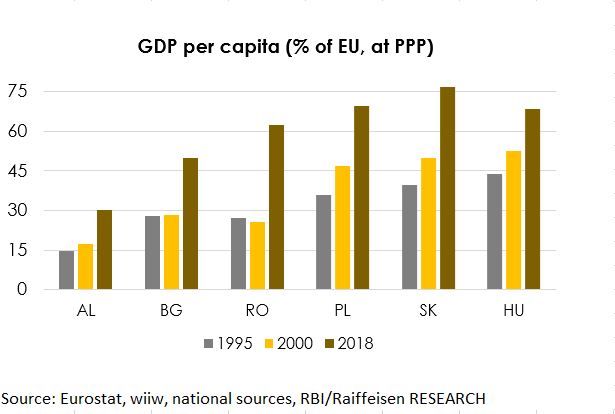

On the ground, the decision is seen in a somewhat less differentiated way. Here the narrative is clear: Albania was not allowed to advance in the EU integration process due to the idea of changing the whole enlargement process and not because of its failure to perform its duties. But scepticism is also appropriate from a superordinate perspective. The French push is alienating in that it is otherwise a pleasure for French politicians to play the geopolitical claviature; but in the case of Albania there are apparently also important domestic political factors (e.g. Albanian labour migrants in France). For purely geopolitical or economic reasoning, the EU could simply be as courageous as it was in the 1990s, when it offered accession perspectives to countries with roughly the same level of socio-economic development as Albania (or other candidates) today.

Albania left in the cold – where’s the vision?

Up to now there has been little clarity on how and when the EU will come to a new concept for enlargement. Therefore, Albania is left without any concrete date, when the question on opening accession talks could be put on the agenda once again. What has happened at the EU level was a blow to the Albanian people’s hope that they have a realistic future as full members of a large European family. The key question after this disappointment is now who the reform driver in the country should be and how reforms can become a winning political strategy for politicians on the ground. Without a clear prospect of EU accession, the door is possibly more open to populism and reform backsliding.

Many senior EU officials and leaders of EU member states have described the failure to open accession talks with the two Balkan countries as a mistake, as they had both met key requirements. In addition, many years of experience with EU members of previous enlargement rounds have shown that laggards in the accession process (e.g. Slovakia) can certainly develop into “model pupils” in some areas, while in countries that were very developed at the time of accession, setbacks can take place (e.g. Hungary). In this respect, Albania, together with the other EU candidates from the Western Balkans, should be given a fair chance in the accession process. Moreover, in recent years the EU has certainly gained new competences through eastern enlargement, as the appointment of a Romanian candidate for the European Public Prosecutor’s Office shows.

The failure of starting EU accession negotiations, regardless of the reason, may also have strong effects on foreign investors in Albania.

Firstly, foreign investors might be shy of taking new engagements. Investors traditionally present in the Balkans will possibly not be deterred too much by the delay in accession negotiations. However, a clear EU perspective and then accession is important to attract new investors (who want to scale business models precisely with the rules of the internal market).

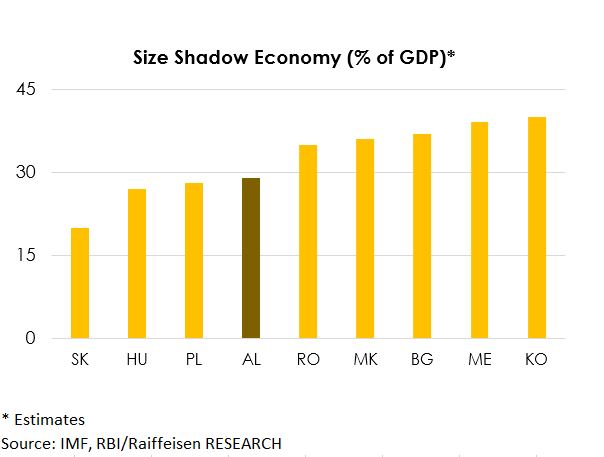

Secondly, from a near-term perspective the delay of accession talks may still lead to a more cautious stance among foreign investors already present in the country. Like people on the street, investors must also assess how committed policymakers will remain to reform – and stability-oriented policies. Businesses currently working in Albania will monitor closely whether the government will be advancing on reform path. The main reforms that are of relevance here are in the following areas: improvement of the judiciary system to ensure a higher legal certainty (by making the constitutional and high courts functional), fight against informality and support for fair competition, fiscal consolidation, transparency in private public partnerships (PPPs). Moreover, emigration may continue, motivated by exactly the ambiguity of the EU, leaving businesses exposed to the increasing lack of skilled labour.

Can Croatia and Germany pave the way?

In order to make progress on the EU enlargement front, relevant bodies and actors must first address the scepticism of France and its proposed reform of the accession process (with the option of breaking off the negotiations). In contrast, it seems rather unfair to link the enlargement process with general EU reform.

That said, there are some signals that the question of opening accession talks with Albania and North Macedonia will be revisited again under the Croatian EU presidency in the first half of 2020 and during the Zagreb Summit (May 2020) in particular. Croatia could at least provide the modalities, which would then be finally fully exploited under the German presidency in the second half of 2020. On a positive note this could put Albania in a shorter test phase, where performance counts. Until then, at the very least Albania must show a committed attitude towards meeting the conditions required by the German Bundestag.

—

This opinion editorial was co-written by Valbona Gjeka, market research senior officer at Raiffeisen Bank Albania, and was first published at Discover CEE.

Add Comment