Since the end of the 1980s, when the centrally planned Soviet economic system entered the final phase of its agony, at least five rounds of region-wide macroeconomic turbulence (which led to currency crashes) have been recorded. These include: the collapse of the Soviet monetary system (1989-1993), monetary instability and high/hyperinflation in the newly established successor states of the former Soviet Union (FSU) (1992-1995), the Russian and Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) financial crisis of 1998-1999, fallout from the global financial crisis of 2007-2009 and the most recent crisis of 2014-2016. Furthermore, some countries have experienced individual currency crises, such as Belarus in 2000 and 2011.

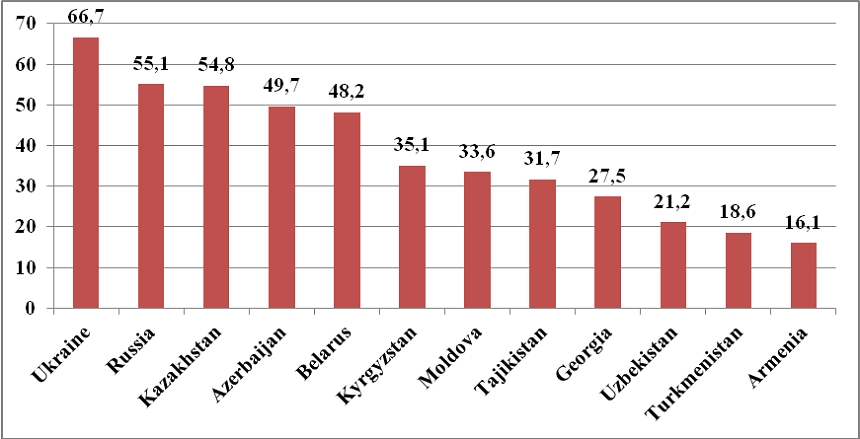

In a similar manner to the 1998-1999 and 2008-2009 crises, the most recent crisis of 2014-2016, which affected nearly the entire region (Figure 1), was caused by a combination of global, regional and country-specific factors.

The global factors included tighter US monetary policy, slower global growth and declining commodity prices – especially oil.

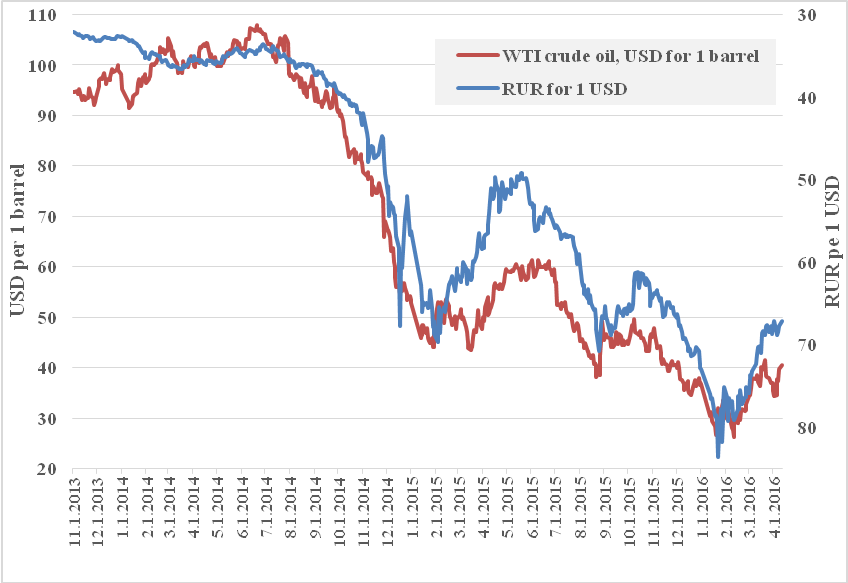

Many analyses focus on the close interrelation between the price of oil and the exchange rate of the Russian rouble (RUR) (Figure 2) and stop there. Indeed, the fact that oil prices more than halved, in the second half of 2014, generated a huge shock to growth prospects, the balance of payments and the fiscal accounts of hydrocarbon exporters such as Russia, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. This list also included Belarus, which had benefited from the transiting, processing and reselling of Russian oil to Western Europe, on preferential terms, for a long time. In addition, the simultaneous collapse of metal and agricultural commodity prices also hit Russia, Kazakhstan, Ukraine and several other FSU countries.

Nevertheless, the size of the depreciation of FSU currencies and the GDP decline were considerably larger when compared with other net oil exporters. This means that other region-specific factors were in play. Amongst the geopolitical factors, the Russian-Ukrainian military, political, and trade conflict and, consequently, the Western financial and economic sanctions against Russia and the Russian counter-sanctions against the European Union and the United States, caused considerable damage, not only to Russia and Ukraine but also to their neighbours—in particular, Russia’s partners from the Eurasian Economic Union.

However, this is not the end of the story. One may ask why the FSU is so vulnerable to various external economic and financial shocks (as in 2008-2009). Especially given the relatively prudent fiscal and macroeconomic policies of oil producers after the 1998-1999 crisis which were reflected in an increase in the central banks’ international reserves, the development of sizeable sovereign wealth funds (during periods of high oil prices) and positive current account balances.

The right answer should point to a legacy of past financial crises which undermined the credibility of national currencies, domestic financial systems and, more generally, state institutions. When an adverse shock hits a highly dollarised economy that has deeply entrenched devaluation expectations, domestic economic agents abandon the domestic currency and immediately withdraw deposits from domestic banks. This is exactly what happened in 1998-1999, 2008-2009, and 2014-2015.

FSU economies also suffer from numerous microeconomic rigidities; structural distortions; insecure property rights; poor business and investment climates; an absence, or weak rule, of law and widespread corruption. To protect themselves against these vulnerabilities and weaknesses in governance, large domestic companies (owned by the so-called oligarchs) remain in close ownership relationships with their foreign subsidiaries or parent companies. This, in turn, helps with capital outflow whenever economic and political uncertainty increases.

To overcome the current crisis, and to prevent new crises, FSU nations must embark on deep structural and institutional reforms. This would allow them to improve their business and investment climates, to eliminate macroeconomic vulnerabilities and to diversify their economies. More specifically, helpful policy changes should lead to the elimination of the administrative “red tape” that discourages business activity and increases business costs.

Law enforcement agencies (which currently act as parasites on business rather than protecting it) should be overhauled; an independent, impartial and more professional judiciary should be instituted and the privatisation of state-owned companies should be returned to. The country should be genuinely opened up to foreign investment; the market should be allowed to price domestic energy supplies; social entitlements (particularly the early retirement age) which are unsustainable in the context of a rapidly ageing population should be reviewed; public investment projects and military expenditures should be rationalised and measures to fight corruption should be legislated.

On the macroeconomic front, a true independence of central banks and constitutionally determined balanced-budget rules are sorely needed, to boost confidence in domestic currencies and domestic financial systems.

The Russian-Ukrainian conflict, which has played a major role in triggering and deepening the current macroeconomic crisis in Russia, Ukraine and the entire region, requires a rapid resolution based on respect for international law and the territorial integrity of each country. A peaceful and sustainable solution would yield high economic pay-offs to each side.

The transition experience of Russia and the former Soviet Union will be discussed during the Special Session on “Russia: A Transition Success or Failure? Or Both?” at the CASE 25th Anniversary Conference The Future of Europe, which will be held from 17-18 November 2016 in Warsaw, Poland. Emerging Europe is a media partner of the conference. Click here to register for the conference.

See Marek Dabrowski, Currency crises in post-Soviet economies — a never ending story?, Russian Journal of Economics, Vol. 2, Issue 3, September 2016, pp. 302-326,

_______________

The views expressed in this opinion editorial are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Emerging Europe’s editorial policy.