As this article was being written, Romania’s death toll from the novel coronavirus stood at 133, easily surpassing Ukraine’s 27 victims, Hungary’s 32, Poland’s 71 or the Czech Republic’s 56, despite comparable numbers of infections in the latter two countries.

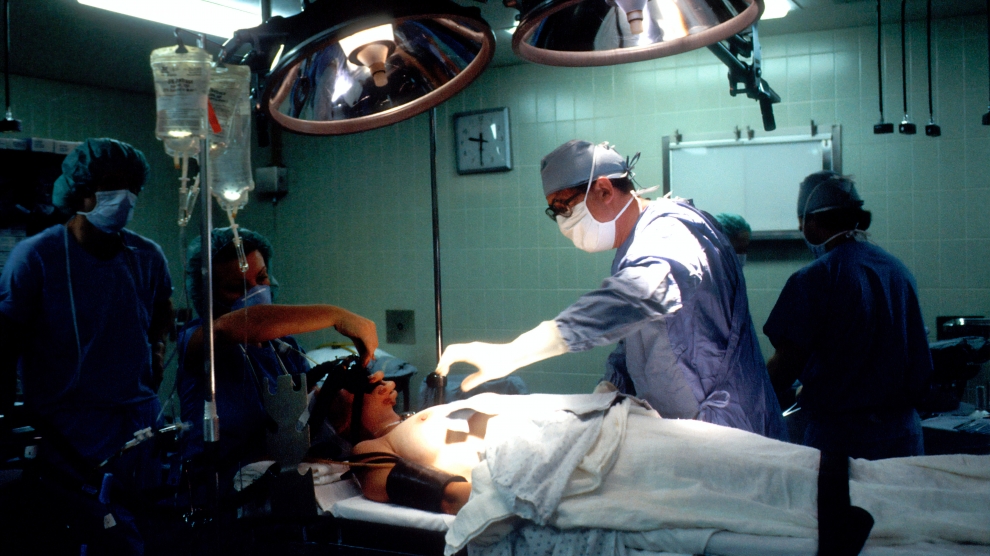

Unlike those in Italy, Spain or New York, hospitals are not overcrowded – so why is Romania seeing more than double the number of deaths than its neighbours?

It’s because another plague stalks the country, joining hands with the coronavirus. That plague is corruption, and unlike Covid-19, it is anything but new. Corruption has long been festering in Romania, and hospitals are hotbeds of infection, something which has become ever more clear during the current pandemic.

An unhealthy practice

On February 26, Romania confirmed its first case of Covid-19. Three days later, the general manager of the emergency hospital in the northwestern town of Baia Mare, Sorina Pintea, was arrested. A former minister of health, Pintea was accused of taking a bribe of 35,000 euros in connection with renovation works carried out in the hospital she managed.

On hearing news of the arrest, Romanians collectively nodded, unsurprised. Corruption in the medical field is nothing new. Almost exactly a year ago, in an initiative that did anything but age well, Pintea – then the country’s health minister in a government led by the notoriously corrupt PSD – announced a new anti-bribery campaign targeting Romanian hospitals after a series of corruption scandals rocked the health system.

Working under politically-appointed cronies in an under-financed sector, many Romanian doctors are known to either directly ask for money from patients or their families, or to require patients to purchase their own medicine and the equipment needed for their care. Others direct patients who can pay towards the private clinics in which they work, an indirect form of bribery.

Ask anyone who has had the misfortune to spend any time in a state hospital in Romania, and they will admit that it is a lottery, even if you factor in the bribes. The prize in this lottery is adequate medical assistance and the avoidance of nosocomial – hospital-borne – infections.

The lottery is rigged against the patient. In 2016, a scandal revealed that a Romanian disinfectant manufacturer, HexiPharma, had been diluting the products that it sold to state hospitals up to two thousand times, reaping massive profits and causing medical equipment everywhere to be sprayed with little more than water. Unsurprisingly, four years later a survey revealed that 60 per cent of Romanians had little or no confidence in state hospitals.

Such is the environment that the novel coronavirus found in Romania, and its spread only further highlights the failings of a corrupt and politicised medical system.

In the northeastern county of Suceava, the most infected part of the country, prosecutors uncovered that officials managing the county hospital, in tandem with the directory of public health, preferentially tested certain individuals even if that meant hospital workers and caregivers in direct contact with infected patients went untested. Suceava currently accounts for 27 per cent of all Covid-19 infections in Romania and for many of the deaths caused by the virus. The entire region has been quarantined and its main hospital placed under military administration.

Rotten at the top

Suceava is not an exception, but the first broken link of a corroded chain.

Romania’s forty-two regional directorates for public health – one for every county – serve as the front line in the battle against Covid-19, running epidemiological investigations to track down those infected and those with whom they have had contact so as to prevent further contamination of the population. Moreover, the same institutions decide who and when gets tested and handle quarantined individuals.

But it is these directorates that have repeatedly shown themselves to be the main weakness in Romania’s current efforts to counter the pandemic, with poor management of resources, faulty communication, a lack of transparency and the endangerment of medical professionals who were forced by their superiors to work without the necessary equipment.

Appointed by whoever was and is in power, as many as 60 per cent of the people running the directorates obtained their jobs without going through a competitive, transparent application process. Almost half have no medical background whatsoever.

No one claps for doctors here

Other nations clap for their doctors, but Romanians do not. It would be too much like clapping for the indifferent accomplices of a system that was deadly even before the coronavirus pandemic. Accomplices who are now quitting or “retiring” en masse so as to avoid the consequences of an environment they know to be non-sterile, equipment they know to be faulty, disinfectant they know to be little more than tap water, colleagues they know to have obtained their degrees from the shady private colleges that abound in Romania, and managers they know to be politruks.

Combined with a testing capacity limited to around 2,000 tests a day nationwide, the medical realities in Romania mean that half of those who died of Covid-19 up to March 31 were diagnosed with the virus after their death or the day they died.

So bad are things in Romania that the dying cannot even be sure that they are dying of Covid-19. They can at least by certain that they are dying of corruption.