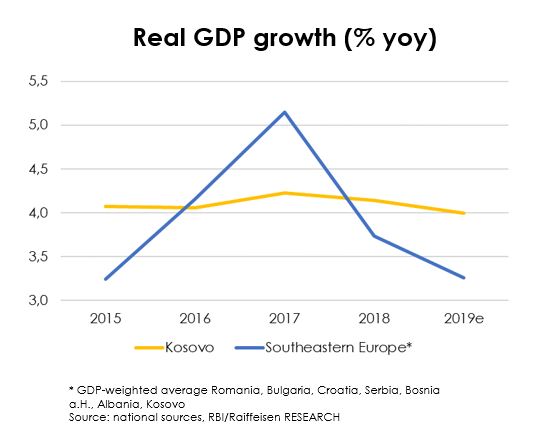

The economy of Kosovo has shown solid and stable real GDP growth of about 4.1 per cent year-on-year on average from 2015-2018, being one of the economies with the highest growth level in the region of Southeastern Europe. However, even an average growth of 4.1 per cent has not been enough to lower the elevated unemployment rate of about 30 per cent. In addition, growth of around four per cent in Kosovo is also well below the average GDP growth of other low and middle-income countries (which stands around 5.5 per cent year-on-year).

It is therefore not surprising that, according to official figures, there has been no measurable convergence of income and wealth levels in recent years. In Purchasing Power Parities, the GDP per capita in Kosovo is well below 30 per cent of the EU average and is thus even lower than in Albania and only slightly higher than in Ukraine.

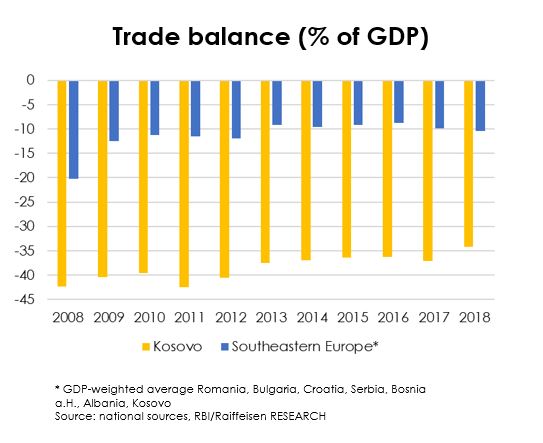

The growth model of Kosovo’s economy has relied chiefly on remittances (which regularly amount to some 15 per cent of GDP), translating into sturdy household consumption. The latter is also the driving factor behind a stunning structural trade deficit. The chronic trade deficit has been well above 30 per cent of GDP in recent years and should be just under 30 per cent this year. But recently growth has started to be supported also by public and private investments, a development that may help to promote a more sustainable (internally-driven) economic development.

Nevertheless, there is a long way to go to boost the sophistication in the economy, to boost the international competitiveness and to lower the external vulnerabilities (including the chronic trade deficit). In this respect increasing export capacities and a stronger private sector would be helpful.

Politics as a drag on growth and EU integration

At present, the signs for growth are not so bad – if it weren’t for politics. Strong economic growth of 4.06 per cent was also reported in the first quarter of 2019, with the support of investments (7.4 per cent), consumption (five per cent) and a lower negative contribution from net exports. The economy of Kosovo has performed well with industrial production on the rise, while exports increased due to a solid performance in goods exports and tourism. Moreover, the banking sector is ready to lend due to a healthy liquidity position and a low level of NPLs. In fact, at below three per cent (the NPL ratios we currently see in markets like Czech Republic and Slovakia) the NPL ratio in Kosovo is among the lowest in the whole CEE region. Higher FDIs and remittances as well as a solid tax collection are also supportive for economic growth.

Although we expect real GDP growth at around four per cent in 2019, supported by public investments (railway and regional road projects financed by IFIs) and private investments (driven by favourable lending conditions and by FDI in the energy sector and in real estate), the risks to this positive outlook are on the rise. The main risks to the economic outlook stem from a mix of slower growth in the EU, delayed public investments and domestic political uncertainty.

The political environment has been rather volatile in recent years, and not all governments were able to finish their four-year mandates. This political volatility is mainly due to fragile governing alliances. After two years, Kosovo is going to hold early parliamentary elections in October after the resignation of the prime minister, Ramush Haradinaj. Kosovo-Serbia relations (including a possible territory swap) were one of the central points of the most recent political controversy. This also includes punitive import duties (at 100 per cent) imposed on Serbian products in November 2018 by the outgoing government. It goes without saying that this move has disrupted the dialogue between Kosovo and Serbia. Bilateral trade between both countries has declined considerably, but this failure can apparently be easily substituted. This is probably due to the low level of sophistication of economic relations. Hence, the macroeconomic effects of the bilateral (or trilateral) trade conflict have up to now been very limited.

Since November 2018, due to the 100 per cent tariffs for Serbian and Bosnian products, the import volume from Serbia has dropped dramatically. From being the largest importer partner country with about 450 million euros of imports a year (14.8 per cent of total imports in 2017), imports from Serbia dropped to 388 million euros or 11.8 per cent of total imports in 2018. As of July 2019, total imports from Serbia amounted to negligible 3.7 million euros or 0.19 per cent of total imports. Imports from Bosnia and Herzegovina (that had a share of 2.7 per cent in total as of 2017) also collapsed, down from 82 million euros in 2017 to 1.8 million euros by July 2019. Meanwhile, total imports have increased to 4.9 per cent year-on-year by end of July, an indication that overall import volumes seem to be hardly affected by the trade conflict.

As already stated, total imports from Serbia and Bosnia were quickly offset by imports from other countries. EU countries were among the main beneficiaries, which from an economic point of view is very reasonable. The EU as a whole is Kosovo’s most important trading partner (import share at around 40-50 per cent, export share at some 25 per cent). Germany (with a share of 12.6 per cent in total imports) is now the most important importer country for Kosovo. Turkey takes second place, then follows China, North Macedonia, Albania, Greece and Italy. In fact, Greece seems to be the largest beneficiary of the tariffs against Serbia, followed by North Macedonia, Turkey and Albania. The realignment of import flows is supposed to have raised the consumer price index from levels around one per cent in 2018 to about 3.3 per cent in the first half of 2019.

Overall, Kosovo remains a net importer country, running a deeply negative bilateral trade balance with nearly all trading partners. However, due to the trade frictions with Serbia and Bosnia, Kosovo now has a trade surplus with both countries. But this is certainly not the way in which a sustainable reduction of the chronic trade deficit can and should take place. And the EU is by no means happy with the trade conflict, despite opportunistic opportunities for some of its members like Greece.

New government will have to do relationship work

Even if 100 per cent import duties on products from Serbia (and Bosnia) sound dramatic, the effects on the Serbian economy – as in Kosovo – are very manageable. The trade volume with Kosovo is estimated at a maximum of 2-3 per cent of Serbian foreign trade. However, the negative political effects are significant. Important political partners of Kosovo (such as the EU or the United States) are very sceptical or even upset as far as the local trade dispute is concerned. There has been little progress in Kosovo’s relations with the EU over the past year. The EU clearly expects efforts to be made towards friendly neighbourly relations between (potential) candidate countries. And without an end to the trade conflict, there will be no material progress in EU integration efforts. So far, Kosovo has fulfilled EU requirements to grant visa-free movement, but the European authorities have not yet come to a decision on the matter.

As the volume of trade with Serbia and Bosnia is of moderate but not of exuberant importance in macroeconomic terms, one could easily start a “trade war”. However, it should also be ended quickly, as the most important trading and political partner by far – as outlined above – takes a very negative view. Therefore, the new government/coalition which will emerge from the early parliamentary elections on October 6, will have to discuss tariffs as soon as possible. Resolving the (trade) conflict, that certainly does not serve the overriding goals of Kosovo and Serbia, will be a key aspect to support Kosovo’s interests in the EU rapprochement process. In addition, political circles in Kosovo should understand, using Bosnia-Herzegovina as an example, that political instability (partly motivated by domestic populism) is not at all conducive to the EU accession process.

—

This article was co-written by Gutner Deuber, head of the economics department at Raiffeisen Bank International, and first published at Discover CEE.