The government may have pulled a controversial ‘foreign agents’ law but Georgia’s decline continues. For those of us who adore the country, this is a deep shame.

In this week’s column I originally planned to write about the Georgia Investment Forum held earlier this week in London, focusing on the investment opportunities the country offers.

But this column is not about the forum — I was invited to chair a session but eventually opted out. It is about Georgia.

- The West must not give up on Georgia

- NGOs at risk as Georgia takes another step back from EU values

- Transit deals are complicating Georgia’s balancing act

I remember my first trip to the country almost a decade ago — a Wizz Air flight to Kutaisi and a welcome bottle of Saperavi wine offered by a border guard officer saying ‘welcome to Georgia’ with a rushed smile on his face.

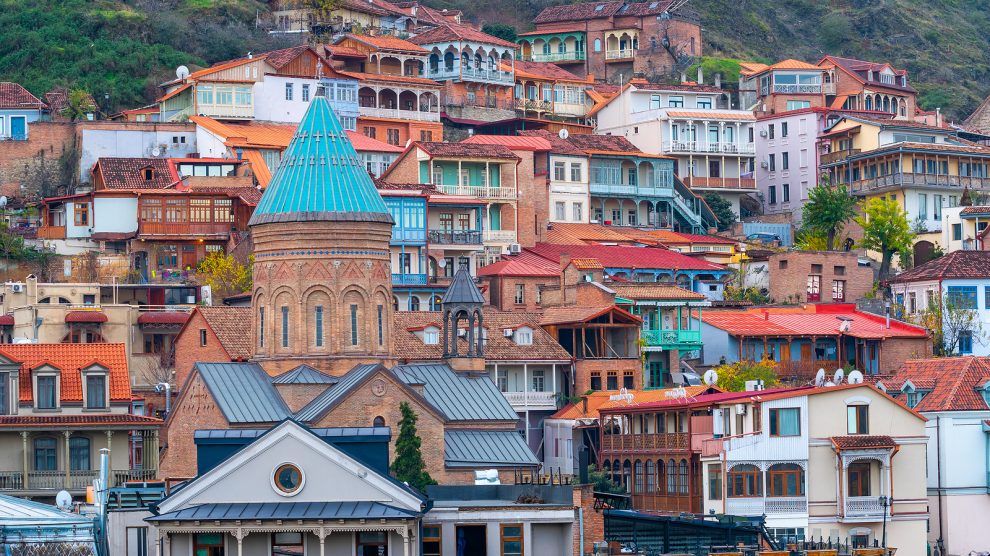

I also remember the incredible number of European Union flags – almost outnumbering national flags – and my hospitable bed and breakfast host learning English from BBC World that played throughout the day in her small grocery shop located close to Tbilisi’s sulphur baths.

I fell in love with the country, its people, its food and wine at first sight. I have visited Georgia many times since and once even stayed in Tbilisi for almost a month, shortly before the Covid-19 pandemic.

Just a few weeks ago, after meeting the Georgian Ambassador to the UK, I spotted a brand-new Georgian restaurant located close to the embassy and just couldn’t refrain from trying my favourite mushroom khinkali — I do not eat meat so traditional khinkali are not an option — and a glass of Saperavi wine. I am always happy to see Georgian food served in Europe and beyond.

‘European’ Georgia?

“Do you think that a staged rally dedicated to Georgia’s presidency of the Council of Europe, with thousands of state employees brought in from the regions to Tbilisi by bus was really necessary?”

I posed this question to Georgia’s then foreign minister David Zalkaliani in December 2019. What he said in response was that, “the European dimension has enormous support in Georgia”.

It does indeed. No wonder the country witnessed massive demonstrations following the announcement of a so-called ‘foreign agents’ bill. If adopted, the bill — dropped as a result of the protests — would have required non-governmental organisations and media outlets to register as “agents of foreign influence” if they receive 20 per cent of their funding from abroad.

Previously, Reporters Without Borders (RWB) had reported that official interference undermines efforts undertaken to improve press freedom in Georgia. In 2021, RWB emphasised, the country saw an unprecedented number of physical assaults on journalists.

The ‘foreign agents’ law was condemned not only by the Georgian nationals but also by the US and the EU.

There is “a feeling of deep concern because of the potential implications of this draft law,” said US State Department spokesman Ned Price at a press briefing.

European Union High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Josep Borrell said the law was a “very bad development” for the country and could seriously affect its ties with the EU.

While 85 per cent of Georgians either ‘fully support’ or ‘somewhat support’ the country’s EU integration, in June 2022, unlike its peers — Ukraine and Moldova — Georgia was not granted European Union candidate status and was given a list of 12 priorities to implement in order to catch up.

‘Neutral’ Georgia?

Shortly after the launch of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine the Georgian government announced that the country did not intend to join any sanctions effort against Russia. Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili said Georgia would hold firm to what he called Tbilisi’s “pragmatic policy” amid a widening international response to Russia’s attack on Ukraine.

“I want to state clearly and unambiguously, considering our national interests and interests of the people, Georgia does not plan to participate in the financial and economic sanctions, as this would only damage our country and populace more,” Garibashvili said.

“While [the government] would sometimes formally appease public opinion and say they are pro-EU, in substance and nature [the government is] a collaborationist regime with Russia that uses Georgians’ fear of war and Russia as leverage,” Giga Bokeria, leader of the opposition European Georgia party said back then.

Just a few days ago, Prime Minister Garibashvili accused Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky of meddling in his country’s political situation by commenting on the protests against the ‘foreign agents’ law.

“When a person who is at war… responds to the destructive action of several thousand people here in Georgia, this is direct evidence that this person is involved, motivated to make something happen here too, to change,” Garibashvili said in an interview with the Georgian IMEDI television station, referring to the Ukrainian president.

“The Georgian authorities are looking for an enemy in the wrong place,” Ukraine’s foreign ministry spokesperson Oleh Nikolenko responded.

A month earlier the Georgian authorities faced another backlash. The city of Tbilisi decided to move ahead with the purchase of new metro rolling stock from a Russian supplier and the perceived openness of Georgian officials to resuming direct flights to Russia also provoked criticism – both domestically and from Western officials.

Will that approach win the interest of foreign investors that Georgia is after? I don’t think so, based on my discussions at least.

‘Transparent’ Georgia?

The World Bank’s Doing Business ranking might be long gone but the country’s investment promotion agency still boasts about the country’s first place in Europe on its main page.

This reminds me of a chat I had years ago with the then Minister of Economy of Belarus Nikolai Snopkov. He said to me while puffing a cigar in his office that Belarus would go up by quite a few notches within the next couple of years. It did indeed — from 63rd in 2014 to 49th in 2020 — ahead of some EU countries such as Croatia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Cyprus and Italy.

It seems the Georgian authorities have a unique liking for international business rankings.

In 2019, a senior official responsible for economy and finance representing a local authority in Georgia reached out to Emerging Europe. They were interested in featuring Georgia in our Future of Emerging Europe Summit and Awards, part of our flagship programme, which acknowledges the region’s achievements. During a video conversation with one of our representatives, the official — probably used to making bets — proposed, openly, that his office would contribute financially if Emerging Europe made sure their location wins an award and he collects a trophy in an Oscar-like ceremony.

The offer was immediately rejected by our representative. We informed several senior government officials about the incident and asked them to take action. It does not appear that they considered it an incident.

What’s more, the authorities are quite selective about which rankings they want to highlight. Perhaps corruption, democracy and freedom matter less.

In Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index 2022 Georgia ranked only 41st. Freedom House says Georgia is only ‘partly free’ and ranks the country 58th globally. The Economist Intelligence Unit concludes that the country is a hybrid regime and places Georgia in 90th position. The level of political culture and how the government functions (both 3.75 points out of 10) contribute to how the country ranks.

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.