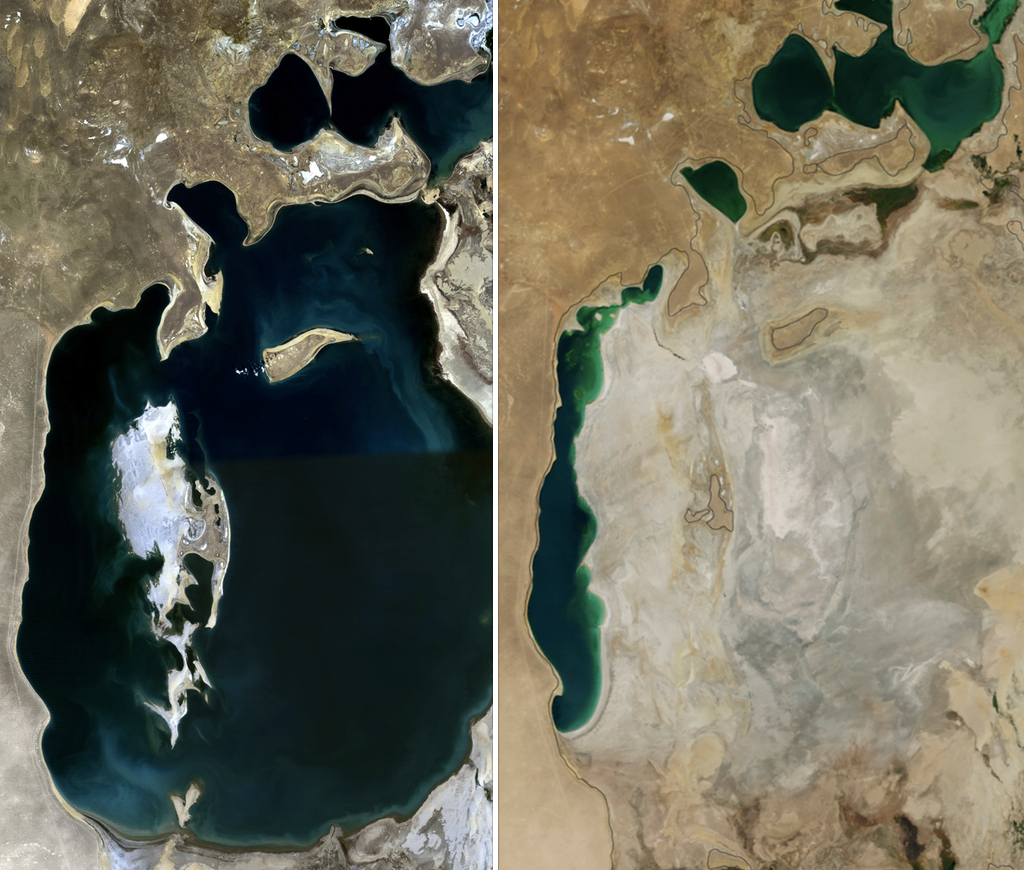

The shrinking of the Aral Sea has been called “one of the planet’s worst ever environmental disasters”. Is there any hope for its recovery? And is the Caspian Sea set to suffer a similar fate?

Stretching across Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, the Aral Sea was once the fourth largest lake in the world, similar in size to the island of Ireland.

For decades now, however, its size has been greatly reduced as a result of Soviet-era mismanagement, poor maintenance, and the worsening effects of the climate crisis. Its dusty remains serve as a grim reminder of environmental malpractice and a glimpse into an increasingly water-scarce future.

- The five Hungarian villages pioneering local solutions to climate change

- Mining companies need to adopt ESG principles

- Creative approaches to reforestation and afforestation: The Armenian experience

A former resident of Moynaq, in the autonomous region of Karakalpakstan, Uzbekistan, remembers a time when the Aral Sea meant bustling fishing villages and days spent by the sea’s shore. “I was five or six the last time I saw ships in the sea when we went swimming,” says Marat Allakuatov.

The ships are long gone, like much of the lake.

Soviet mismanagement

This is largely down to years of Soviet-era mismanagement on a truly monumental scale. In 1960, the USSR took the decision to use the vast, arid plains of the region surrounding the Aral Sea for cotton farming, a water-heavy crop. Lacking sufficient hydraulic infrastructure, the Soviet state began an immense plan to divert two rivers, Sir Darya and Amu Darya, through a 500 kilometre-long channel to irrigate the cotton fields. Diverting the rivers – which fed the Aral Sea – deprived the lake of much of its water flow.

By 1980 the damage had been done. Just 10 per cent of the original water flow from the two rivers was reaching the lake. By 1989, the lake had split into two, and by 1997 it was just 10 per cent of the size it had been 40 years previously. As much as 95 per cent of nearby reservoirs and wetlands turned to desert, and more than 50 lakes in the rivers’ deltas dried out. By 2014 the eastern part of the sea had completely disappeared.

While the surrounding desert did bloom for a while, the Aral Sea’s desiccation has had unprecedented, and tragic implications.

The sea became stuck in a negative feedback loop, where shallower water would heat quicker, causing it to evaporate faster, again and again. This then raised salt levels, and the water became polluted with fertiliser and pesticides. Dust storms now form in what was once the sea bed, degrading soil with salt and chemicals for hundreds of kilometres. Biodiversity has dwindled and the region’s entire climate has become harsher, without the regulating force of a large mass of water.

Decline in biodiversity

“Declining water levels and increasing salinity led to a major decline in biodiversity,” explains Professor Anson Mackay of University College London, who specialises in the impact of climate change on fresh water systems. “There were over 20 fish species recorded in the lake in the early 1970s, but these had all disappeared a few decades later. Of course, mammals, birds and other aquatic life were also decimated.”

However, as Professor Mackay tells Emerging Europe , the sheer scale of the destruction has been felt on a social and economic level too, affecting the populations of the fishing villages that once dotted the shoreline.

“This had knock-on effects for local and regional economies dependent on a once thriving fishing industry. The lake’s waters grew more toxic as pollutants became more concentrated, leading to increased disease amongst populations living in the region.”

In regions such as Karakalpakstan, the destruction of the sea, along with pollution and dust storms, saw extraordinarily high rates of death from respiratory disease, and also increased TB, typhoid and dysentery from increased bacterial contamination; cancer rates and anaemia increased, as well as, tragically, increased infant morbidity and mortality.

Many people have now left the Aral region entirely, where rusted boats lie in the middle of a desert, ghosts of fishing communities long gone. The local economy simply evaporated along with the sea.

“As the sea disappeared, the people staying there became unemployed,” says Mr Allakuatov. “The older generation lost their hope for the future.”

Obstacles to recovery

Cross border competition for water, continued mismanagement, bureaucratic impediments, as well as rapidly accelerating climate change now stand in the way of any hope for recovery.

“Management of the lake’s catchment certainly contributes to the continued demise of the Aral. As cotton plantations persist, especially in Uzbekistan, it’s doubtful that inflow via the Amu Darya will ever be enough to replenish the lake,” explains Professor Mackay, who believes that the further construction of gas refineries on the Uzbek side stand as proof that there is no hope of restoration.

As the fate of the lake became an infamous geographical case study in environmental malpractice, attention focused on how to mitigate its negative effects. The United Nations launched a programme in Uzbekistan called the Multi-Partner Human Security Trust Fund for the Aral Sea Region. However, the focus of the programme is on helping communities, reducing poverty, and enhancing resilience, which, while important, does suggest that there is no aim to rejuvenate the sea itself.

Kazakhstan has at least had some success at preserving what is left. In a last-ditch effort in 2005, the Kok-Aral project was launched with the support of the World Bank, which built a dam between the northern and southern parts of the sea, preventing water from flowing into the south and boosting water levels.

The programme has led to some fish and aquatic life returning to the northern part of the lake to such an extent that fishing has again become a viable industry for some.

Masood Ahmad, the World Bank team leader who launched the project, was surprised at the extent of its impact. “At that time, we were not expecting this much flow and the success has been astounding.”

However, this protection of the northern part of the Aral Sea has come at the expense of its southern section, which has continued to degrade. This merely highlights the need for cross-border political cooperation, as the worsening climate crisis catalyses its demise and reinforces the need for restoration.

This has led many to call on the international community to do more. Especially when the region surrounding the lake is transboundary and the Amu and Syr Darya rivers run though multiple countries, with all having a say in how its water is managed.

“But globally we need to pay attention as well,” argues Professor Mackay. “Is, for example, the clothing/textile/fashion industry doing enough to support the sustainable use of cotton? Undoubtedly not. Internationally, bodies need to keep putting forward initiatives to help people on the ground affected by climate change, and multinationals, along with our general capitalist society, need to do more to ensure that the goods we buy are sustainable.”

Is the Caspian Sea next?

As if the plight of the Aral Sea were not enough, the far larger Caspian Sea is also now in danger.

A report published in Nature magazine in December claims that sea levels in the Caspian Sea are projected to fall by nine–18 metres in medium to high emissions scenarios by the end of this century, caused by a substantial increase in lake evaporation that is not balanced by increasing river discharge or precipitation.

According to these new projections, twenty-first century Caspian sea level decline will be about twice as large as estimates based on earlier climate models. A decline by nine–18 metres will mean that the vast northern Caspian shelf, the Turkmen shelf in the southeast, and all coastal areas in the middle and southern Caspian Sea emerge from under the sea surface.

In addition, the Kara-Bogaz-Gol Bay on the eastern margin will be completely desiccated. Overall, the Caspian Sea’s surface area will shrink by 23 per cent if sea levels drop nine metres, and by 34 per cent if they drop 18 metres.

Decreasing Caspian sea levels will have geopolitical ramifications and an impact on the economies throughout the region, say the report’s authors, Matthias Prange, Thomas Wilke and Frank P. Wesselingh.

Shipping traffic inside and outside the Caspian Sea, which is connected to the World Ocean by the Volga-Baltic Waterway and the Volga-Don Canal, will be affected, with consequences for maritime trade and naval access. Coastal infrastructure including ports will become obsolete as waters recede. Shrinkage of the Caspian Sea might further affect future claims by the five littoral states on the coveted oil and gas reserves.

The need for global awareness

The lack of public and political awareness of the imminent Caspian sea level decline applies equally to the worldwide lake level changes driven or amplified by global warming.

The authors are therefore calling for a global awareness campaign concerning future climate-driven lake level changes.

“In particular, we propose to pay considerable attention to this issue in future Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports as well as in the next Global Assessment Report by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.

“We also call for scientific programmes to assess risks and vulnerability with respect to worldwide lake level decline and to provide guidance in decision-making. Finally, we suggest to establish a global task force to develop and coordinate transboundary mitigation and adaptation strategies, assisted by the recently launched World Adaptation Science Programme (WASP) hosted by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), which is envisaged as an interface between adaptation research and decision makers. International climate funds can offer an opportunity to finance projects and adaptation measures if changes in lake levels are attributed to climate change.”

If the Caspian Sea should, heavens forbid, suffer the same fate as the Aral Sea, nobody will be able to claim that they were not warned.

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.