The European Union is going through some very hard times. The European Commission’s White Paper, which puts forward five scenarios on the Union’s future, is quite eloquent about the tremors that are undercutting its foundations. However, in order to make good policy judgements about the future one has to keep history in mind. The last decade was quite momentous for Romania and it does pay to glance back at it.

The EU has been a powerful force for change in a weak institutional setting. This influence was being felt even before Romania’s accession to the EU in 2007. The acquis communautaire embodied a roadmap that helped to summon domestic resources and find a strategic purpose. There is now talk among local politicians and business leaders of finding a new anchor (e.g. Euro adoption).

This seems to be a sensible stance for a country that still has weak institutions and needs benchmarks for collective action. In addition, belonging to the core of the EU is a commendable aim. But, while EU benchmarks are relevant, they cannot put a country on automatic pilot when it comes to surmounting economic gaps and working out concrete public policies. Besides, the Euro area has institutional and policy arrangements that badly need overhauling.

There has been considerable progress during the past decade. Millions of Romanian citizens are travelling, living and working abroad; there has been a modernisation of organisational patterns and know-how transfers have taken place. Considerable productivity gains took place after EU accession, but there have not been enough of these to make an all-around and decisive breakthrough. It is also fair to say that things became increasingly blurred once the EU started to be buffeted by a series of crises.

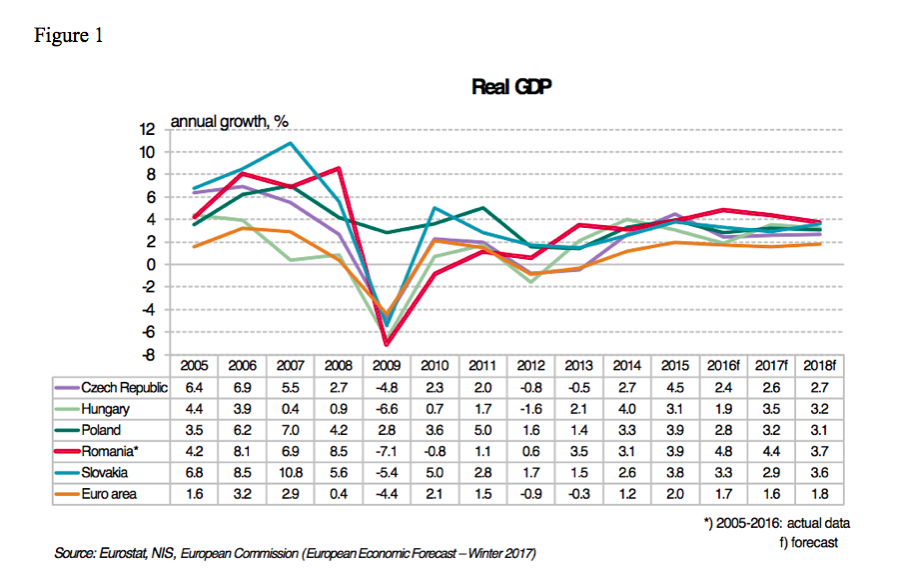

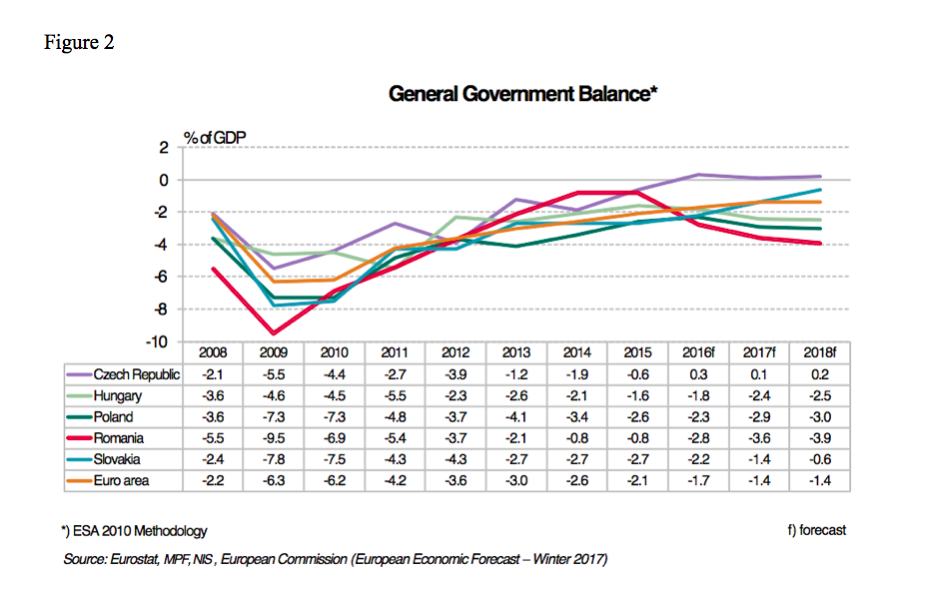

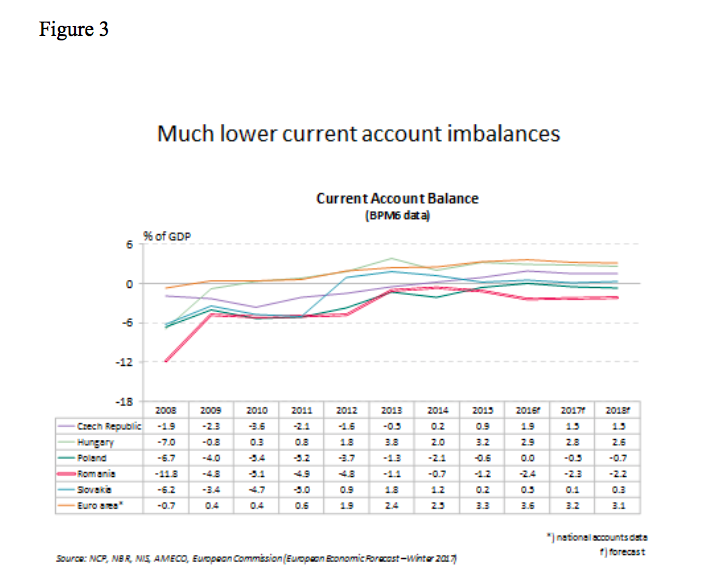

The liberalisation of financial flows and the huge differentials between Romanian prices/wages and those in the more developed states of the EU have invited troubles and volatility, as well as increased social polarisation. Pro-cyclical policies have played a role in this regard. Figure 1 shows how economic growth rates sank in Romania, and other EU emerging economies, in 2009 before a sort of catch-up process began again. A legitimate question is ‘how durable is this new upswing’. Massive corrections of fiscal and external imbalances took place after 2009 (see Figured 2 and 3).

Tied to the EU

There has been a dismemberment of more than a few industrial production chains, some of them presumably obsolete, with a subsequent exodus of human capital. Migration has become a big irritant over time, however much one values remittances as a source of balancing external accounts. About three-quarters of Romania’s exports go to EU markets and the local banking sector is heavily controlled by European groups. The persistent malaise of European economies, especially those in the Eurozone, is a handicap for Romania’s economic growth.

A Euro adoption hinges on two fundamental preconditions. One is a critical mass of real convergence as a means of withstanding the pressures within the Eurozone (Romania’s GDP/capita is currently cca 57 per cent of the Eurozone average in PPP terms). This is one of the major lessons of the Eurozone crisis. It is wishful thinking to believe that this precondition can be tackled in just a few years’ time. The second precondition is to have the Eurozone in a better shape institutionally and policy-wise by the time of joining it. Membership in the European banking union would make sense given the heavy local presence of foreign banks.

Efficiency reserves exist in all societies and one assumption could be that these are where massive productivity gains could easily be achieved. Nevertheless, moving towards the production possibilities frontier in a highly inefficient system is not easy, when the policies that foster economic growth are hard to articulate and institutions are weak. Mobilising internal resources implies, in most cases, the overhaul and upgrade of public administration. The functioning of public administration is crucial for an efficient absorption of European funds and for better public investment. Public policies should focus on the expansion of tradable sectors and upgrading output. The bottom line is that all these endeavours call for better-functioning domestic institutions and structural reforms, including superior management of state companies.

Mobilising domestic resources

Romania’s institutions would have to go from being ‹extractive› to being ‹inclusive›. This would also involve a taxation system that provided a sufficient amount of resources to the public budget to improve public services and keep social polarisation in check. Fiscal revenues are among the lowest in the EU as a share of GDP – about 26 per cent in 2016 against an average of over 40 per cent for the EU. Taxation policy has to convey a message of fairness to citizens, most of who have been severely battered by the financial and economic crisis. Fairness involves combating tax evasion and tax avoidance (profit shifting).

Industrial rejuvenation and the modernisation of agriculture depend on the development of infrastructure (highways, irrigation systems, upgrading the railroad network, the drinking water system, the sewage system, etc.), and this is where Romania is lagging considerably behind other EU countries. A poor infrastructure significantly offsets Romania’s labour cost advantage; EU funds could help to overstep this stumbling block.

There is a need to rethink the growth model. This does not mean that Romania should be less friendly to foreign inward investment. Economic also to be more inclusive and better underpinned by knowledge and innovation. A better resource allocation, more targeted on higher valued tradeable sectors and an efficient absorption of EU funds could increase potential growth by 1-1.5 per cent of GDP annually (from a current potential growth of around three per cent). A revamped growth model would help to overcome the middle income trap.

Going forward

How should public policies be improved in the years to come? Well, by strengthening institutions, setting clearly defined investment priorities, allocating resources on a multiannual basis, and by taking measures to insulate institutions from predatory vested interests. It is important to try to diminish the human capital exodus, to foster institutional values and professional standards, to allocate more resources to education for which expenditure should rise above five per cent of GDP. The country also needs to mobilise internal resources and to avoid pro-cyclical policies that worsen macroeconomic imbalances; the late fiscal policy slippage (see Figure 2) has to be reversed and the budget further consolidated.

It is essential to deal with budget sub-optimality, for it causes an insufficient amount of required public goods (too few resources for education and health care). For this to happen fiscal, revenues should climb above 30 per cent of GDP and nearer to the average of other NMSs. Romania needs to reform its education in conjunction with a significant rise in R&D expenditure and to foster more investment which should enhance domestic production of higher value-added goods and services. This should be followed by a strong push to develop infrastructure (EU funds have a major role to play in this respect), and the country should take industrial policy measures that enhance higher value-added production and tap into the huge potential of agriculture

The prospect of economic stagnation, over wide stretches of Europe, is looming while shifting economic power in the world complicates the global environment for Europe’s emerging economies. In such a context, Romania needs to mobilise its internal reserves, absorb EU funds on a large scale and efficiently, undertake extensive reforms in the public sector, while promoting entrepreneurship and innovation as the means of raising its economic growth potential and offsetting adverse shocks.

_______________

The views expressed in this opinion editorial are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Emerging Europe’s editorial policy.