The Polish prime minister’s agenda has more to do with eradicating his predecessors, Law and Justice, than restoring the rule of law.

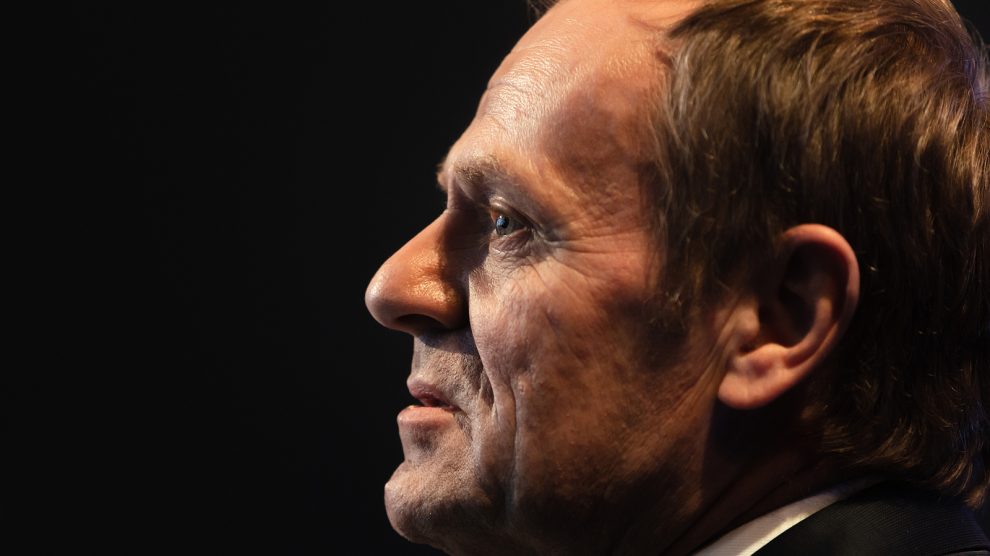

One month into his latest term in office as Poland’s prime minister, Donald Tusk has wasted no time to confront the controversial state apparatus that his predecessors, Law and Justice (PiS), had built over eight years. But the bold actions of his government appear to be focused on silencing the PiS opposition rather than making genuine efforts to strengthen the rule of law in Poland.

- No, Poland doesn’t have any ‘political prisoners’

- The EU has been very good for emerging Europe

- ‘Donald Tusk is one of few Europeans who knows how the EU works’

The Polish justice minister, Adam Bodnar, has put forward a bill that overhauls the National Council of the Judiciary (KRS), Poland’s constitutional body that protects the independence of courts and judges. Under Law and Justice, members of the KRS were appointed by the-then ruling nationalist-conservative party. Bodnar’s legislation aims to reverse this by reintroducing the selection of judges by peers. The overhaul of the KRS is necessary to restore the courts’ impartiality and unlock the billions of EU funds frozen when PiS were in power, according to the justice minister.

The same line of argument used by PiS

The legislative reform of the KRS comes amid a fierce backlash from Jarosław Kaczyński, the leader of Law and Justice, and his supporters over the radical steps taken by the new government. Since his return to office last December, Tusk has seized back control of the state-run media from PiS loyalists and detained two former ministers as they attempted to seek refuge in the presidential palace. This sparked a large anti-government protest in Warsaw led by Kaczyński, who told the demonstrators that Tusk posed an existential threat to the Polish state.

While Bodnar’s proposal may be justifiable in the case of the politically-compromised KRS, it nonetheless follows the same line of argument that Law and Justice used to explain its own reforms. The lengthy Round Table talks resulted in a negotiated outcome to Poland’s exit from communism in 1989, which meant that the former communist elite were left in positions of power. During its time in office (2015-23), PiS too faced criticism, but defended its judicial changes as essential to address the presence of corrupt, post-communist elites in state institutions.

The difficulty PiS faced with its reckoning of Poland’s unclean break from communism is not dissimilar to Tusk’s challenge to confront the nationalist-conservatism of Law and Justice today. The new Polish prime minister has vowed to press ahead with his removal of PiS appointees, including the governor of the central bank, Adam Glapiński. But Poland’s president, Andrzej Duda, has sided with the opposition after the arrests of the two former ministers and denounced Tusk’s actions as a violation of the law.

Despite the constitutional crisis its actions have created, the Tusk government’s reforming agenda has received support from the European Union. “Rest assured that the Commission stands by your side,” the European Commission president, Ursula von der Leyen, told Tusk as the Polish prime minister promised to act swiftly to reverse the judicial reforms enacted by Law and Justice. It is an unequivocal indication that the EU is prepared to support an overhaul of the judiciary, but only if it aligns with its political interests.

Double standards

The EU’s support of Tusk’s reforms inadvertently provides Law and Justice with a powerful argument to mobilise its voters. A central part of PiS appeal to more socially-conservative voters has been its staunch defence of Poland’s sovereignty and traditional Catholic values. The willingness of the Tusk government to take decisive action with little consideration for its constitutional implications may drive this section of the Polish electorate to rally behind PiS ahead of the local elections in the spring.

But perhaps more dangerously than PiS’s potential revival, the backing of the European Commission for Bodnar’s judicial changes risks exposing the EU to accusations of double standards over the rule of law. The EU invoked Article 7 of the Treaty on European Union against Poland under the Law and Justice government for putting the justice system ‘under the political control of the ruling majority’. However, despite the legislative intervention in the KRS to remove PiS appointees along with the possible cancellation of rulings, no such EU disciplinary measures have been taken.

Poland’s effort to strengthen its democratic system of government deserves to be applauded, but this does not mean giving Tusk or any other Polish government unconditional support. Tusk’s drastic actions have thrown Poland into a protracted constitutional crisis. To restore the rule of law and political stability, efforts should be made to find consensus rather than undermine the opposition.

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.