A post-war economic boom will not, alone, be enough to keep a majority of Ukrainians at home. Ukrainians want security, and will not accept anything less than Russia’s military defeat.

Even before the Russian assault on Ukraine began on February 24, our demographics were already very poor, with the population falling from 52.2 million in 1993 to 41.2 million at the end of 2021.

The natural decrease of the population (the difference between the mortality and birth rates) has cut the number of Ukrainians by 7.8 million since 1993, while the Russian occupation of Crimea and Donbas decreased the population of Ukraine by 2.3 million.

Migration prior to the end of 2021 meanwhile, is officially at 0.9 million but in reality 3.5 million Ukrainians of working age were accounted for as labour migrants while 2.7 million Ukrainians of working age were invisible to the tax system, meaning that a large number of those might also be abroad in some illegal form.

- Ukraine’s start-up scene remains resilient, but needs support

- Aid agency warns of increased resentment to Ukrainian refugees unless changes made immediately

- The horrors of life in Ukraine under Russian occupation

Migration tendencies has always been a sensitive topic for the Ukrainian authorities, but Russia’s aggression made the issue critical. According to the United Nations, as of August 17, 6.2 million people have left Ukraine since the start of the war and 3.7 million have registered for temporary protection in Europe. Up to 1.4 million people are recorded as refugees in Russia but many of them have been forcefully passed through filtration camps from the occupied territories.

The numbers are not accurate, just estimates, but they still give a clear picture of how seriously the Ukrainian population was affected by Russia’s aggression.

Migration is aggravated by the fact that this outflow does not include men of military age who are prohibited to leave the country during wartime. This means that a new wave of migration is still ahead when martial law is lifted.

After the shock of the first months of the war, some Ukrainians are already returning home, but we can hardly count those returns as an indication to stay in the country. Many people fled in a rush at the start of the war but now, after returning, many might be considering taking enough time to get prepared thoroughly (like selling assets) for radical changes in their lives.

Security is the main reason for strong migration sentiments. Ukraine was not rich, but it used to be safe. Even after the 2014 war, for a majority of Ukrainians, potential Russian aggression was more a horror story rather than a realistic scenario.

After February 24 everything changed. Missile strikes reach the most distant parts of the country. Russians often target civilian infrastructure including schools, hospitals and kindergartens. The threat of a new assault from the north (from Belarus) remains on the agenda and keeps the western parts of Ukraine in permanent tension. Living under permanent airstrike alerts and regular missile attacks is completely different to what Ukrainians used to dream of.

Surveys regarding migration offer a mixed picture. The reason is that Ukrainians live in the context of “emotional swings”. It also depends on how you ask people about their plans. If you ask Ukrainians whether they plan to return after the war, nearly 90 per cent will respond positively, according to multiple surveys.

At the same time, two-thirds of refugees do not plan to return until hostilities come to an end, according to a UNHCR survey.

No ‘partial’ solution

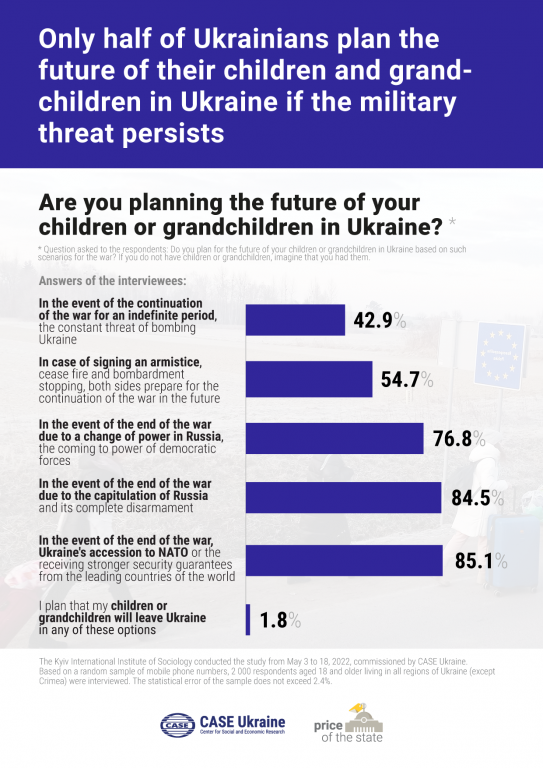

CASE Ukraine solicited a survey asking Ukrainians how they see the future of their children, considering different scenarios for the outcome of the war. In this way, we hoped to see the essence and bypass patriotic sentiments, which are soaring (people are ashamed to say openly they plan to leave the country forever). Results appeared alarming – near 50 per cent of respondents reported their intention was to leave the country if the war ends in some “intermediate form” (such as a truce or peace treaty) and not the total defeat of Russia.

This poses a huge dilemma for the Ukrainian leadership, ruling out any “partial solution” to the Russian aggression. To put it differently, any weakness in resolving “the Russian problem” will transform into a severe demographic crisis, with millions of people of working age leaving the country while millions of pensioners and disabled stay, a burden on the social security system of the devastated country.

Such sentiments promise nothing good for European countries as well. The EU may be experiencing a shortage of workers, but 20 million displaced people looking for safer places around the globe might be too much even for developed countries like Germany, France and Italy.

We hear many voices from the West calling for a “peaceful solution” with Russia, hoping that life will return to normal as soon as some “compromise” is achieved. But this illusion looks reasonable only from silent and peaceful European cities.

For Ukrainians, the reality is totally different. We are revising our reality and are revisiting our plans for the future almost every day, depending on the news from the frontline. We understand that only the military defeat of Russians on the battlefield will bring security to our country and confidence in our future. Otherwise, many of us, too many, will be forced to start a new life creating multiple inconveniences for host countries via pressure on wages, the social security system, and healthcare.

Security is essential

One way or another, security is the primary issue for Ukrainians revising their migration sentiments. Surveys report that welfare and comfort became non-essential for society. Only nine per cent of displaced people report jobs as an important reason to return, and just four per cent claimed that rebuilt infrastructure might be reason to return. The overwhelming majority of respondents name security and the end of war as the incentive for them to return to Ukraine, although 13 per cent of displaced people reported they will return anyway, whatever happens.

Against this backdrop, it looks like bringing more weapons to Ukraine and resolving “the Russian dilemma” militarily is the only investment that can calm down migration sentiment. The Ukrainian leadership talks a lot about the inevitable inflow of billions of euros after the war ends. And it is taken as granted that the economy will boom after the aggression is repelled.

However, despite this widely-advertised economic boom, the main focus is on the war, and we understand that a lot will depend on how it comes to an end. Any weaknesses on the Ukrainian side will be an invitation for more aggression from Moscow, and any “concession” will be a clear signal for millions of Ukrainians that it’s time to say farewell to the country forever.

Building a life in a country doomed to experience a new assault in three-five years (while Russia is assembling forces for a new push), is unacceptable for most people, even in a booming economy.

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.