When the United Kingdom attempted to secure a deal with the World Trade Organisation for its re-entry to the Government Procurement Agreement, it came up against an unexpected objection, from Moldova.

Yet the objection had little to do with trade. Instead, it centred on the fact that Corina Cojocaru, Moldova’s economic counsellor to the WTO and the wife of the country’s foreign minister, was – along with her team – denied a UK entry visa and was unable to travel to the UK.

“Nobody listened to us for six to seven months,” she said in a telephone interview with Bloomberg. For Mrs Cojocaru, the visa issue represents a bigger problem: if her delegation could not get a visa for crucial negotiations, then Moldovan suppliers aiming to bid for projects in the UK cannot hope to compete with companies from nations with much easier access to the country.

In the aftermath of the controversy, Moldova’s Minister of Foreign Affairs and European Integration Tudor Ulianovschi held talks with the Director for Eastern Europe and Central Asia in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) in London, Martin Harris – a former UK ambassador to Romania – to discuss various issues of mutual interest. Mr Ulianovschi made clear that the visa process was a major hindrance for the access of Moldovan citizens, and economic suppliers, to the public procurement market in the UK, outlining the need for visa simplification.

Brexit’s latest obstacle

Moldovan concerns do appear to have driven the FCO to consider the issue of visa simplification, and a number of meetings have already produced effective results.

As such, in November 2018, Moldova announced that it was now supporting the UK’s re-entry to the WTO’s Government Procurement Agreement, and that the two countries were developing mutually beneficial relations, “including the creation of favourable conditions for the economic players and the Moldovan community in the UK, in the context of the new migrational policies which will be adopted by London post-Brexit.”

And yet Moldova, described by the Economist last year as “Brexit’s latest obstacle” is not the only emerging European country whose citizens encounter substantial problems when applying for UK visas.

In June 2018, a leading Ukrainian website, European Pravda, launched a campaign to re-introduce visa requirements for UK citizens, who have enjoyed visa-free travel to Ukraine since 2005.

“Ukraine is not Cambodia” read a headline criticising the UK’s visa policies towards Ukraine on the website of the Ukrainian think tank on migration and visa issues, Europe Without Barriers. The piece drew attention to the fact that in 13 per cent of cases, Ukrainians were refused a UK visa, a similar refusal rate to Cambodia. Moreover, even when visas are issued, it is often too late for their recipients, resulting in missed planes, disrupted travel plans and business meetings and prevention of athletes from competing in competitions.

A prominent Ukrainian economist and former deputy finance minister, Olena Makeieva, received her visas after her plane had left on each of the three occasions she had applied over the past 10 years. “A two-minute Google search could have verified her identity. But the British needed over a month to grant her a visa,” noted the news portal Euromaidanpress. Similarly, Ukrainian journalist Ekaterina Sergatskova could not travel to the UK to receive the Kurt Shock Award she had won, as the UK Home Office claimed it could not clarify the purpose of her trip.

Not cheap and not fast

Then there is the cost. The fee for processing a UK visitor visa for Ukrainians ranges from 110 euros for short-term trips to 946 euros for a stay of up to 10 years. Furthermore, Ukrainian applications are processed in Warsaw, prolonging the issuance of the travel document. An accelerated service is available (which allows the decision to be taken in five days), but costs an extra 251 euros. However, the five-day timeframe is not guaranteed, and some applicants requesting the “urgent” service have had to wait two weeks or more, again disrupting travel plans. “The British visa procedure can be characterised as not cheap and not fast,” says Ms Kateryna Kulchytska of Europe Without Barriers.

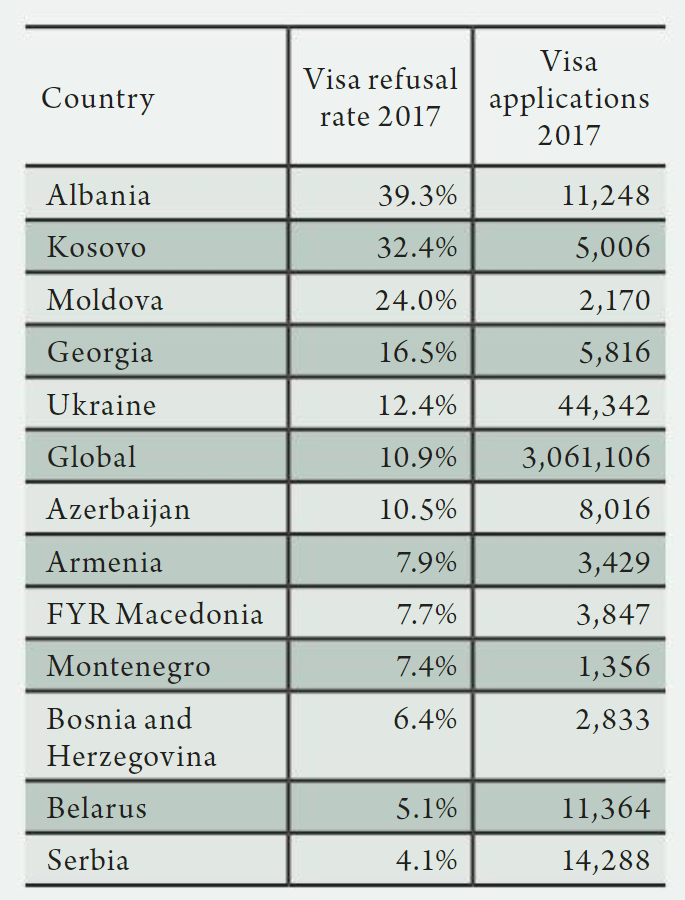

A closer look to the visa refusal rates of emerging Europe countries whose nationals need to be in possession of visas in order to enter the UK legally confirms that Ukraine, along with Albania, Kosovo, Moldova and Georgia had higher percentages of visa denials compared to the global average in 2017. Figures for the first three quarters of 2018 are much the same.

“The main problem is not complicated requirements, rather the approach of UK Visas and Immigration – which is not clear,” Sergei Aleinik, Belarusian ambassador to the UK and a former deputy foreign minister, tells Emerging Europe. While refusals for Belarusian citizens are below the global average, Mr Aleinik is looking forward to a flexible stance towards sports delegations, cultural representatives, charity organisations and children. In the past, the rejection of visa applications the Belarus women’s national football team hindered their participation in an international competition in the UK. “The cultural and humanitarian dimension of mobility should be more favourable,” Ambassador Aleinik adds.

One victim of an unexpected visa rejection was Nadza Dzinalija, a University of Amsterdam student originally from Bosnia and Herzegovina, who intended to participate in an academic conference organised by Glasgow University. Immigration officials were doubtful about her intention to return home after the event even though she had already booked return flights. Although the decision was later overturned because of a vast amount of media coverage of her case, such instances demonstrate procedural flaws even in countries where the overwhelming majority of applicants receive visas.

What risk?

The United Kingdom has steadfastly refused to simplify its visa criteria with non-EU emerging European countries based on rather arbitrary “migratory and security risks.” Few people are aware of what these “migratory and security risks” actually are.

The latest figures (for 2017) for emerging European citizens illegally found to be present in the UK are very low, exceeding 100 only in the case of Albania (3,760) and Ukraine (555). However, the number of Ukrainians illegally present in the UK is lower than that of Ukrainians in the Schengen states. As for Albania, the country has signed a readmission agreement with the United Kingdom, meaning that there is an institutional framework addressing the return and readmission of Albanian citizens from the UK found to be living in the country illegally.

While it could be argued that a more simplified or liberalised visa regime would increase migratory pressures on the UK, the extent of illegal immigration is not expected to be significant. The UK authorities can prepare an impact assessment for particular countries, scrutinising current migratory risks (if any) and the situation of marginalised groups, before reaching an agreement on visa facilitation or liberalisation.

Moreover, declaring even the holders of diplomatic passports from specific countries (such as Ukraine) as “security threats” raises serious questions. Instead, an impact assessment for emerging European states covering the fight against terrorism, trafficking in human beings, drug trafficking, organised crime and corruption would provide a better understanding of whether or not there are any security issues which could appear if visa processing was simplified.

The way forward

In order to solve the problem of the high number of visa rejections, the UK should take a simplified, less restrictive approach. Indeed, research in the field of migration studies has concluded that more migrants move irregularly to those countries with restrictive migration policies.

In light of the UK’s migratory and security concerns, a gradual visa liberalisation model similar to that of the EU could be adopted. Before fully liberalising the visa regime, an agreement on visa facilitation may be signed, in order to simplify the legal migration for certain categories of people (such as holders of service and diplomatic passports, sports and cultural representatives, charity organisations, academics), reduce the costs of visas and accelerate procedures. At the same time, the United Kingdom may conclude readmission agreements with particular emerging Europe countries and tie the simplification of visa processing to the successful implementation of these agreements.