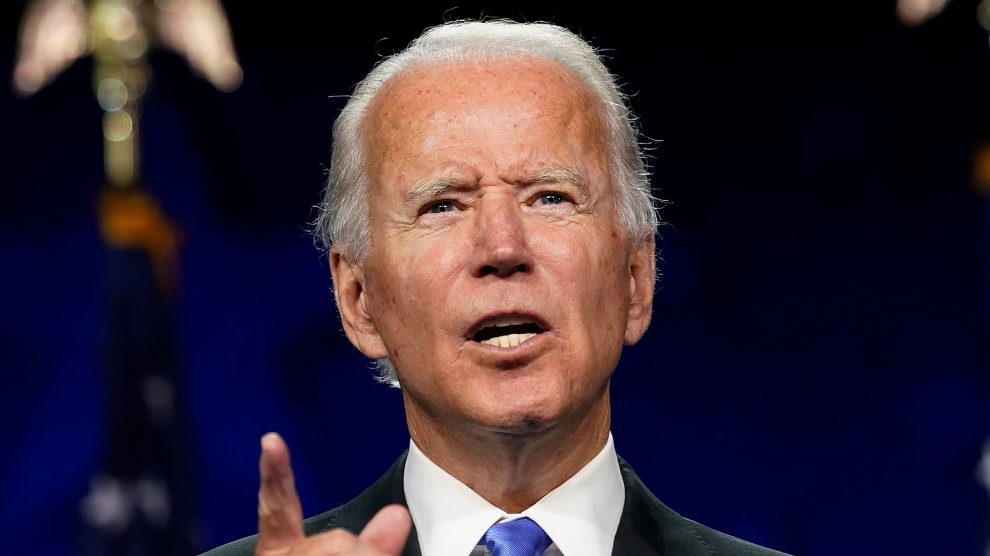

Joe Biden’s recent decision to recognise the Armenian genocide has been welcomed by Armenian communities around the world. But what does it imply for the future of US relations with the Caucasus region?

US President Joe Biden broke from convention on April 24 to become the first sitting United States president to recognise the genocide of Armenians which took place during World War 1.

The date of the recognition was significant: it marked the 106th anniversary of the beginning of the genocide, in 1915.

- Conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh is far from over

- What to expect from Armenia’s snap election

- The four most remarkable sights in the Caucasus

“On this day, we remember the lives of all those who died in the Ottoman-era Armenian genocide and recommit ourselves to preventing such an atrocity from ever again occurring,” said Biden.

News of the recognition came as no surprise. The previous day, Biden made his first call to his Turkish counterpart, Recep Tayyip Erodgan, during which he informed Erdogan about his intentions to recognise the genocide.

Unsurprisingly, the reaction from Ankara was negative.

Turkey officially claims that no genocide occurred – that the Armenian deaths which did happen were hugely inflated and that “only” a “few hundred thousand” died as a result of a combination of war, disease and relocation rather than a concerted effort to exterminate them.

“After more than 100 years of this past suffering, instead of exerting sincere efforts to completely heal the wounds of the past and build the future together in our region, the US president’s statement will not yield any results other than polarising the nations and hindering peace and stability in our region,” said Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu.

Nikol Pashinyan, prime minister of Armenia, meanwhile welcomed the recognition.

“I highly appreciate your principled position, which is a powerful step on the way to acknowledging the truth, historical justice, and an invaluable of support [sic] for the descendants of the victims of the Armenian genocide.”

Rift with Turkey

For many, the recognition has been another indicator of the growing rift between the United States and its longtime ally, Turkey.

Although the statement was carefully worded – the Ottoman Empire is mentioned instead of Turkey, and Istanbul’s previous name of Constantinople is used – it has still attracted the ire of the Turkish government and its supporters.

By the time genocide began in 1915, the Ottoman Empire had for decades been reeling from rebellion after rebellion, in which it lost much of its European territory and Christian subjects. The various wars of independence fought by Balkan peoples saw many atrocities committed against Muslims and ethnic Turks.

This series of losses made the late Ottoman Empire increasingly vengeful, desperate and militaristic. In the build-up to World War I, there had already been several incidents of massacres against ethnic Armenians and other Christian subjects of the Ottoman Empire, such as Assyrians and Greeks.

In early 1915, the Ottomans suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of the Russian Empire in the Battle of Sarikamish, in what is now eastern Turkey. The government accused the largely Armenian population of the region of treachery through collaboration with the Russians.

What followed was a years-long campaign of terror against ethnic Armenians. Some studies estimate that as many as 1.5 million Armenians were killed. Survivors scattered all over the world, giving birth to the sizeable Armenian diaspora.

The killings of those years have continued to be a sensitive topic, not least because of the continuous denials made by successive Turkish governments. Today, some 30 nations have formally recognised the events as a genocide.

However, US recognition of the genocide has been continuously delayed. The Republic of Turkey, which emerged from the ashes of the Ottoman Empire, has for much of its history had been a crucial ally of the United States, particularly during the Cold War.

Turkey’s control over the Bosphorus and its border with the Soviet Union made it strategically important in containing the United States’ main adversary. United States nuclear weapons have been based in Turkey since 1959 and the Turkish military has enjoyed substantial US financial support.

This cooperation continued after the Cold War. Turkey still has NATO’s second largest, and arguably second most powerful, military. During the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, Turkey played a major logistical role in supporting the US-led war efforts.

However, in the past decade or so, these warm relations have been deteriorating – and this latest development appears to be a continuation of this trend.

Past US presidents have tiptoed around the issue of the Armenian genocide. Although Barack Obama had pledged to recognise the genocide during his presidential campaigns, he fell short, instead referring to the events by the Armenian phrase “meds yeghern”, meaning “great crime”. Donald Trump used the same phrase to refer to the genocide.

Turkey’s regional ambitions

But over the past few years, particularly since the beginning of the presidency of Recep Tayyip Erdogan in 2014, Turkey has been at loggerheads with the United States as it seeks to assert itself as a regional power. Erdogan went so far as to blame the United States for an attempted coup in 2016. Last year, Turkey was kicked out of the United States’ F-35 programme, under which it would have received dozens of advanced fighter jets. Prior to that, despite repeated warnings from Washington D.C., Turkey had bought the S-400, a Russian-made air defence system.

Another bone of contention has been Syria. The United States’ main partner on the ground is the YPG, a Kurdish militia which has been battling ISIS and other extremist rebels in Syria, often in conjunction with forces loyal to Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad.

According to Turkey, the YPG has substantial links to the PKK, a Kurdish armed group that has been fighting against the Turkish state since the 1980s. Many within Turkey go so far as to claim that the YPG and the PKK are one and the same. Although the PKK is recognised as a terrorist group by several western nations, including the United States, the link to the YPG has been rejected.

Turkey has so far made at least two military incursions into Syria targeting the US-allied YPG. Although the US has never stood in Turkey’s way – before every operation, United States military personnel were evacuated – the utility of the YPG as the only reliable partner for the US-led coalition in Syria has further frayed relations between Washington and Ankara.

Now, Turkey has been throwing its weight around more, possibly leading to escalating alarm among its erstwhile western allies. It provided substantial support to Azerbaijan during its recent war with Armenia in Nagorno-Karabakh, which ended in a clear victory for the Azeris. Turkey supplied advanced military hardware, including domestically-produced combat drones which proved to be decisive in defeating the Armenians. Furthermore, Turkey allegedly sent thousands of its Syrian proxies to Nagorno-Karabakh – although the state denies this.

Biden’s statement could indicate that the United States will take an even firmer stance towards its longtime ally. However, as long as Turkey is in NATO, it is unlikely that any substantial action – such as sanctions or revocation of membership – will come to pass. Nonetheless, Turkey’s ability to assert its power may be limited in the future, as it will not receive the same level of diplomatic support as before.

As for Armenia, Biden’s recognition is welcome for a country which has been racked by political turmoil since its defeat in Nagorno-Karabakh, and faces a snap parliamentary election later this summer.

Recognition of the genocide is a step in the right direction, but will need to be followed up by more concrete forms of support.

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.