Throughout Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia, the Covid-19 pandemic has compounded existing democratic flaws, including weak checks and balances, persistent corruption, a proclivity in some places for strong leaders, and pressures on media freedom, according to the latest edition of the Economist Intelligence Unit’s annual Democracy Index.

Government-imposed lockdowns and other disease-control measures led to the withdrawal of civil liberties on a massive scale, causing score downgrades across the vast majority of countries in the latest edition of the Economist Intelligence Unit’s annual Democracy Index.

Every region of the world experienced a democratic rollback, but the removal of individual liberties in developed democracies was the most remarkable feature of 2020.

- In emerging Europe, corruption is undermining Covid-19 fight

- ‘A dark day’ as Poland rolls back reproductive rights

- Just how much influence does Russia have in Bosnia and Herzegovina?

In the 2020 edition of report, which provides a snapshot of the state of democracy worldwide, the average global score fell from 5.44 (on a scale of 0-10) to 5.37. This is the worst score since the index was first produced in 2006. A large majority of countries — 116 of a total of 167 (almost 70 per cent) — recorded a decline in their total score compared with 2019. Only 38 (22.6 per cent) recorded an improvement, and the other 13 stagnated.

Elite governance becomes the norm

“The pandemic confirmed that many rulers have become used to excluding the public from discussion of the pressing issues of the day and showed how elite governance, not popular participation, has become the norm,” says Joan Hoey, the editor of the report. “The willing surrender of fundamental freedoms by millions of people was perhaps one of the most remarkable occurrences in an extraordinary year — most people accepted their governments’ decisions to take away their rights and freedoms.

“But we should not conclude from the high level of public compliance with lockdown measures that people do not value freedom. Most people simply concluded, on the basis of the evidence about a new deadly disease to which humans had no natural immunity, that preventing a catastrophic loss of life justified a temporary loss of freedom.”

In 2020 Eastern Europe and Central Asia’s average regional score in the Democracy Index declined to 5.36, compared with 5.42 in 2019. This is markedly below the region’s score of 5.76 in 2006, when the index was first published. Only a handful of countries, such as Poland, registered a significant improvement in their scores, while many more experienced steep declines in their scores, most notably Kyrgyzstan.

In total, the scores of ten countries rose in 2020, while 16 fell and one stagnated.

“This clear trend of deterioration across the region indicates the fragility of democracy in times of crisis and the willingness of governments to sacrifice civil liberties and exercise unchecked authority in an emergency situation,” reads the report.

“The pandemic also served to highlight persistent problems in the region, such as poorly functioning institutions and a weak political culture. Eastern Europe’s low average score for political culture (4.67) is the worst of any region and reflects a worrying decline in support for democracy — a symptom of a deep democratic malaise and popular disenchantment with the political status quo in the region and increasing support for military rule and strongman leaders.”

Estonia leads

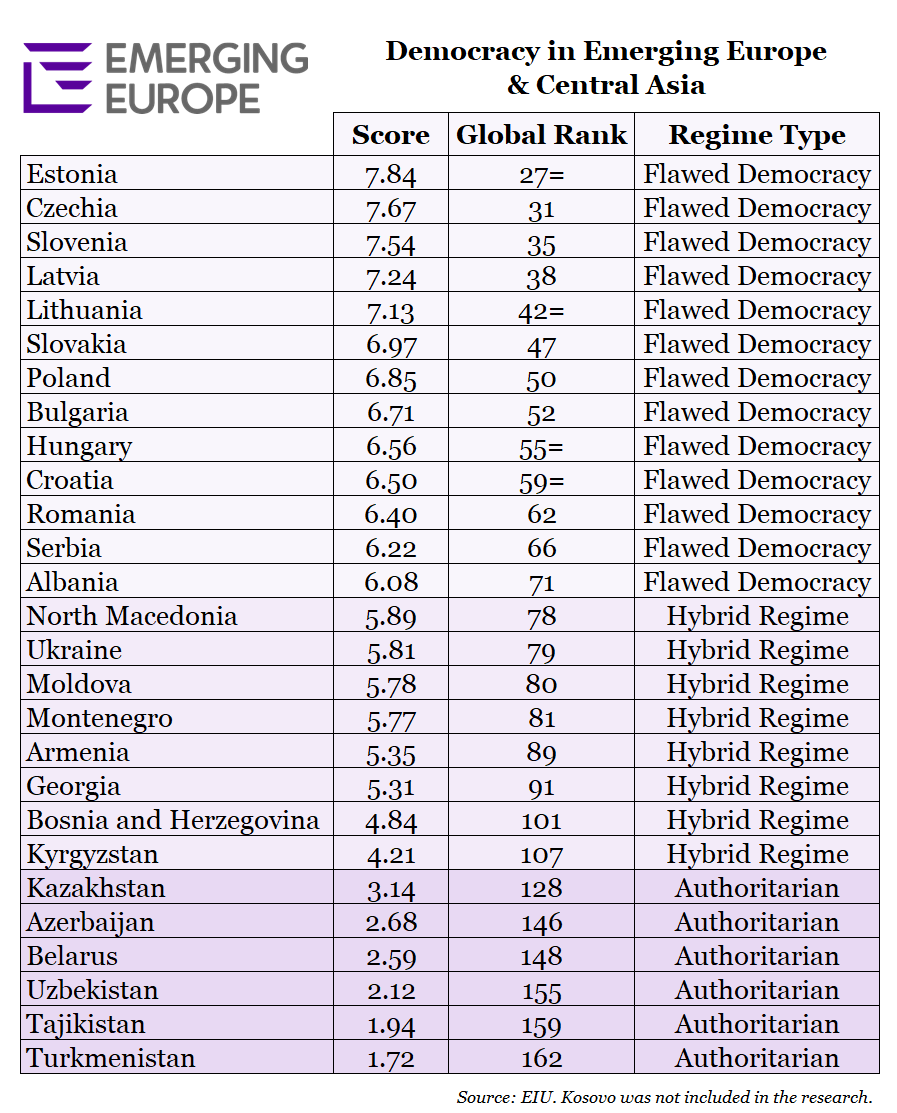

Estonia continues to lead the region, but there are still no countries classified as “full democracies” in either Central and Eastern Europe or Central Asia, and only Albania changed its category in 2020, improving to a “flawed democracy” from a “hybrid regime”.

Albania’s upgrade was driven by several factors, including an increase in public support for democracy. The government also undertook a series of electoral reforms that seek to bring Albania’s election laws in line with EU standards as the country prepares for the start of EU accession talks. However, it remains unclear whether the reforms will result in completely free and fair elections.

Overall, 13 countries are now classed as “flawed democracies”, including all of the region’s 11 EU member states plus Serbia and Albania; eight are classed as “hybrid regimes” (the remaining Western Balkans states plus Ukraine, Moldova, Armenia, Georgia and Kyrgyzstan).

The rest, including Belarus, Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan, are “authoritarian regimes”.

In Central Europe the gap between the highest-scoring countries — Czechia and Slovenia — and the rest of the region has become even more pronounced. Poland was the exception.

The country’s score improved as support for democracy and readiness to participate in lawful demonstrations increased, as illustrated by a wave of anti-government protests in the second half of the year, while support for strong leaders decreased. However, Poland still remains significantly Czechia and Slovenia, but has now overtaken Hungary, where the prime minister, Viktor Orbán, wielded even more unchecked executive power in response to the pandemic.

Perhaps most surprisingly, the score of Belarus – still classed as a dicatorship – improved in 2020.

Another unfree and unfair presidential election in August 2020 caused a wave of peaceful demonstrations that demanded the resignation of the president, Alexander Lukashenko.

However, while Mr Lukashenko remains in power in the face of the months-long protests, which have been brutally repressed, the report concludes that the election improved the political culture of the country by increasing public interest in and engagement in politics and undermining public trust in strong leaders.

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.