Dozens of tree-covered market squares in Poland have suffered the same fate in recent years, with local authorities opting to ‘rejuvenate’ them with concrete and cobblestone instead of more labour-intensive greenery. But there are signs things may be changing.

Urban renewal projects in Poland are typically carried out under the name of revitalisation, a clear misnomer as they have nothing to do with bringing anything back to life.

Indeed, they often lead to the country’s pretty, iconic market squares becoming deserted, avoided by locals and visitors as unbearably hot in the summer and just plain ugly the rest of the year.

- The transformation of Budapest’s iconic City Park

- Disco polo: Kitsch and unsophisticated, but big business

- Destination communism: How holidays to Eastern Europe were sold before 1989

The trend itself has been dubbed more aptly as concreteosis – a portmanteau of ‘concrete’ and a disease-implying suffix – and was first brought to the public attention by Jan Mencwel, a social activist who has published a book about the problem (Betonoza. Jak się niszczy polskie miasta).

Back in the communist era in the 1960s and 1970s, squares in Poland abounded with freshly-planted trees, bushes and lawns. After decades of trademark socialist neglect, however, greenery became something of a public nuisance, with tree roots damaging pavements, leaves and branches falling on cars and lawns becoming overrun with weeds.

Fast forward to the 21st century and the unruly greenery is now giving way to concrete in many such places. In his 2020 book, Mencwel discusses dozens of Polish towns where green squares were transformed into cobbled deserts, decorated with just a few potted trees here and there.

The makeover is always sold to the public as a success, a problem taken care of. The local mayor is eager to present himself as a man (or woman) of action before his term is up, and there is nothing like a bit of ribbon-cutting to drive that message home.

Steep learning curve

Meanwhile, climate experts have been sounding the alarm louder and louder with each passing year. Long written off in Poland as unwarranted panic-mongering, the warning finally begins to ring true for many local authorities up and down the country.

Some of them have learnt their lesson the hard way. In Włocławek, a small town in central Poland on the Vistula river, the market square was first modernised in 2013 for a hefty seven million złoty (just under 1.5 million euros).

Trees and lawns were replaced with hundreds of square metres of granite slabs, resulting in what Polish people usually refer to as a “frying pan”. On summer days, the surface of the square now heats up to nearly 50 degrees Celsius, while benches become searing to the touch.

What must have been equally painful for the municipal authorities was the barrage of criticism that followed the square’s unveiling. Eventually, they listened: the authorities caved in last year and announced a plan to regreen the square – a one million złoty (approx. 213,000 euros) project with the telling name of Market Square – The Green Heart of the City.

The right balance

Paved areas in cities are known to contribute to rising global temperatures through the so-called urban heat island effect. According to a recent estimate by medical journal The Lancet, there were 356,000 heat-related deaths worldwide in 2019 alone.

Other than heat, concrete also traps water. With fewer and fewer green areas to soak up heavy rainfall, in many cities around the world it never just rains anymore, it floods.

Jan Mencwel, author of the book on Polish concreteosis, believes it’s all about striking the right balance between paved and green areas in cities.

“Greenery can coexist peacefully with other spaces. It’s also very beneficial for business,” he tells Emerging Europe. “If we want a square or a street to become an attractive shopping destination, then greenery is the way to go. People prefer shopping in areas with trees and shade.”

Mencwel also claims shoppers tend to spend more money in such places.

“Nature makes people relax. When an area is shaded in the summer, shoppers aren’t forced to flee from heat as soon as they leave a store. They can have a look in another one or perhaps get a drink in an outdoor café.”

There are also plenty of great examples that Poland’s municipal authorities can follow: unsurprisingly, some of the best come from the Netherlands.

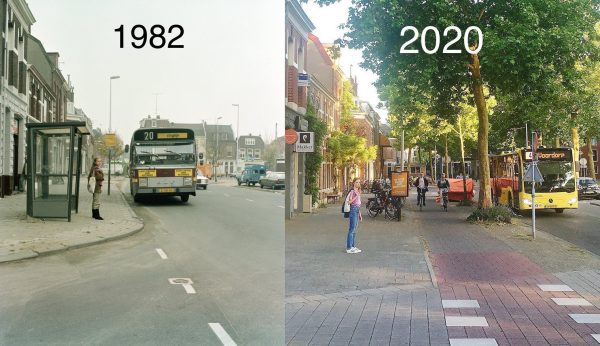

Consider the following two photos, taken in the same place in Utrecht 38 years apart, recently shared on Twitter by the UK Noise Association:

For anyone living in a concrete jungle thinking that there’s little hope, it’s worth remembering that the Netherlands, now the gold (or should that be green?) standard, has not always been the gold standard. Change takes time, but you have to start somewhere.

In Poland, Włocławek is as good a place as any to start that change.

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.