The Eurovision Song Contest is more popular than ever, but the increasingly high costs of staging the event risk leaving smaller, poorer countries unable to pay the entrance fee.

Bulgaria last week became the latest country to pull out of the 2023 Eurovision Song Contest, just days after Montenegro and North Macedonia both confirmed that they will not be competing in next year’s event.

- Fo Sho: The Ukrainian hip hop phenomenon with Ethiopian roots

- Watch out Eurovision, Moldovan legends Zdob și Zdub are back

- A political sing-song

Bulgaria did not offer a reason for its withdrawal, but both Montenegro and North Macedonia cited the cost of taking part.

“Such a decision is in the best interest of the citizens, taking into account increased costs due to the energy crisis, which occupy a large part of the budget of the service, as well as the increased registration fee for participation in the contest,” said MRT, North Macedonia’s public broadcaster, in a statement.

Montenegro’s public service broadcaster RTCG meanwhile said that, “in addition to the significant costs of registration fees, as well as the cost of staying in Great Britain – we also faced a lack of interest from sponsors, so we decided to direct existing resources to the financing of current and planned national projects.”

“The question of cost, sadly, isn’t new,” says William Lee Adams, founder and editor of Wiwibloggs, the world’s most followed Eurovision blog.

“Montenegro previously declined to take part in 2020 and 2021 (and before that in 2010 and 2011). At the time an official stated that the broadcaster needed to update its fleet of cars for safety reasons.

“Bulgaria sat out the event in 2019. Their return largely hinged on record labels and artists funding participation themselves.”

Other countries in the emerging Europe region have also missed out for financial reasons. “In the past 10 years we’ve seen countries including Ukraine, Croatia, Poland, and Bosnia and Herzegovina exit,” Adams tells Emerging Europe.

“Most of them subsequently returned, sometimes just a year later.”

Romania meanwhile was disqualified in 2016 over unpaid bills to the European Broadcasting Union (EBU), the contest’s organisers, before paying up and being reinstated a year later.

Other absences have been political. Armenia did not enter the 2012 event in Baku, Azerbaijan, citing security concerns. This was despite Azerbaijan temporarily amending its visa policy to allow Armenians, who are normally barred from entering the country, to attend the event.

Hungary has declined to compete since 2019, a move widely believed to be a response to Eurovision’s ongoing promotion of diversity and tolerance, which are in stark contrast to the anti-LGBT+ policies of the Budapest government.

Liverpool stands in for Kyiv

The 2023 contest will be held in Liverpool, in the United Kingdom, after this year’s winner, Ukraine, was unable to take up hosting duties due to Russia’s invasion.

The winning country normally hosts the following year’s contest, but Sam Ryder’s second-placed finish this May led the UK to be asked to step in because of the Russian invasion.

Ukraine’s 2022 winners, the Kalush Orchestra, will nevertheless be an integral part of the event in Liverpool next year, and have said that, “Playing in the same place that The Beatles started out will be a moment we’ll never forget.

“Although we are sad that next year’s competition cannot take place in our homeland, we know that the people of Liverpool will be warm hosts and the organisers will be able to add a real Ukrainian flavour to Eurovision 2023.”

Eurovision is a co-production funded by the host broadcaster (in next year’s case, the BBC) and the other participating broadcasters who pay a fee to take part.

While the EBU does not make public the costs involved, nor the fee each individual country is required to pay, the BBC is expected to spend anywhere from eight to 17 million euros on next year’s event.

The total amount collected from other participating broadcasters is believed to be around six million euros.

More countries at risk

For host cities, the cost is justified, according to Michela Favaro, the deputy mayor of Turin, which hosted this year’s event.

She told the BBC earlier in August that while the city had spent 10 million euros on Eurovision, the amount the city got back from visitors “was considerably higher than the investment”.

But for those countries which often don’t make it past the semi-finals, the costs are increasingly being seen as unjustifiable. None of the three countries which have pulled out over the past two weeks has ever won the event.

At this year’s Eurovision, all three were eliminated at the semi-final stage.

“Producers have a tougher time selling the show internally — and justifying its costs — when they aren’t represented in the grand final,” says Adams.

“For smaller countries, nation branding and the chance to remind the world that they exist are the central reasons to compete.”

While Adams points out that the 37 countries will take part in the Liverpool event next year represent smallest number of participants since 2014, he adds that Belarus and Russia no longer participate because of geopolitical tensions (and their bad behaviour).

“Were we to factor them in, we’d have 39 countries, which fits well within the range of recent years.”

As for the future, Adams nevertheless concludes that, “inflation and the rising cost of participation puts more countries at risk of withdrawing”.

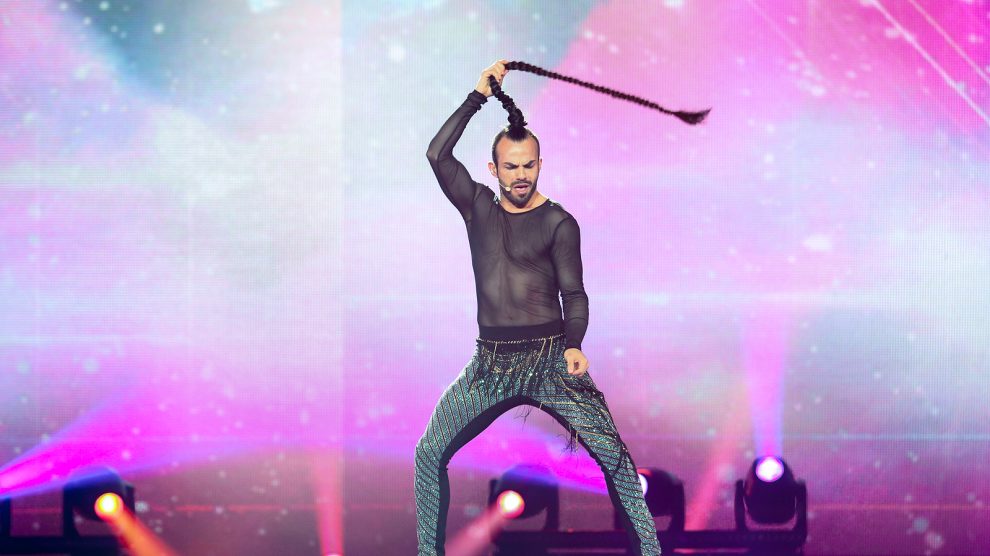

Photo: Montenegro’s Slavko Kalezic at the 2017 Eurovision Song Contest, held in Kyiv.

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.