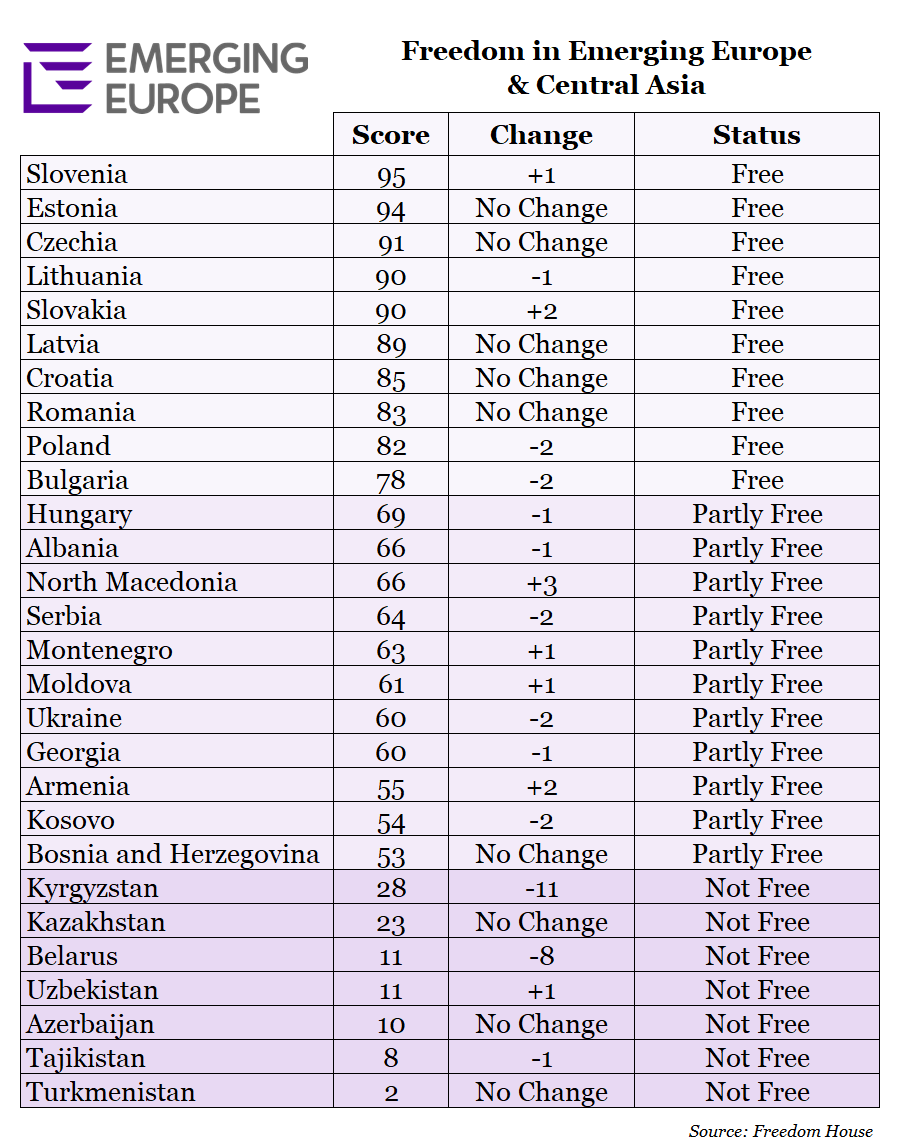

Freedom in the World 2021, published by US-based research and advocacy group Freedom House, finds that fewer than a fifth of the world’s people now live in fully free countries. In emerging Europe and Central Asia, just 10 of 28 countries are classified as fully free.

Authoritarian actors grew bolder during 2020 as major democracies turned inward, contributing to the 15th consecutive year of decline in global freedom, according to Freedom in the World 2021, the annual country-by-country assessment of political rights and civil liberties published by Freedom House, a US-based organisation that conducts research and advocacy on democracy, political freedom, and human rights.

- Poland and Hungary are gunning for the social media giants

- Central Asia’s resource curse

- Sadyr Japarov: New hope for Kyrgyzstan or a return to autocracy?

“This year’s findings make it abundantly clear that we have not yet stemmed the authoritarian tide,” says Sarah Repucci, vice president of research and analysis at Freedom House.

“Democratic governments will have to work in solidarity with one another, and with democracy advocates and human rights defenders in more repressive settings, if we are to reverse 15 years of accumulated declines and build a more free and peaceful world.”

The report finds that the share of countries designated Not Free has reached its highest level since the deterioration of democracy began in 2006, and that countries with declines in political rights and civil liberties outnumbered those with gains by the largest margin recorded during the 15-year period.

The report downgraded the freedom scores of 73 countries, representing 75 percent of the global population. In emerging Europe and Central Asia, 12 countries saw a decline in freedom in 2020, while just six improved their scores.

Slovenia scores the highest (95/100), Turkmenistan the lowest (2/100).

Decline and improvement

The region’s largest declines in freedom were seen in Belarus and Kyrgyzstan, while the most improvement came in North Macedonia.

In Belarus, the government claimed that the incumbent president Alexander Lukashenko won an August presidential election with 80 per cent of the vote, though the results were widely denounced as fraudulent.

The campaign and election period featured an unfair candidate registration process, the detention of candidates, widespread internet disruptions on election day, and the violent crackdown on peaceful protesters demanding their right to a fair vote.

Protesters in Kyrgyzstan meanwhile damaged government offices and forcibly released high-profile prisoners in October amid demonstrations against the conduct of that month’s parliamentary elections. While the results were annulled two days after the polls, violence continued as the month progressed; supporters of nationalist politician Sadyr Japarov, who was among those freed from custody, intimidated and attacked opposition groups seeking to form a transitional government.

Japarov became acting president and prime minister in mid-October, after the protests prompted the resignation of President Sooronbay Jeenbekov and Prime Minister Kubatbek Boronov. Japarov resigned from both posts in November to qualify for a presidential election due in January 2021, which he won.

In North Macedonia, July’s parliamentary elections produced a virtual tie, with the governing Social Democratic Union of Macedonia (SDSM) taking 35.89 per cent of the vote, and the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation–Democratic Party for Macedonian Unity (VMRO–DPMNE) winning 34.57 per cent.

The polls were competitive, credible, and took place without major incident, and the SDSM formed a governing coalition with smaller parties shortly thereafter. In October, the EU signaled that it was prepared to start accession negotiations before the end of the year. In November, however, the Bulgarian government blocked the start of talks.

The effects of Covid-19

Government responses to the Covid-19 pandemic exacerbated the global democratic decline. Repressive regimes and populist leaders worked to reduce transparency, promote false or misleading information, and crack down on the sharing of unfavorable data or critical views. Many of those who voiced objections to their government’s handling of the pandemic faced harassment or criminal charges. Lockdowns were sometimes excessive, politicised, or brutally enforced by security agencies. And anti-democratic leaders worldwide used the pandemic as cover to weaken the political opposition and consolidate power.

In fact, many of the year’s negative developments will likely have lasting effects, meaning the eventual end of the pandemic will not necessarily trigger an immediate revitalisation of democracy. In Hungary, for example, the government of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán took on emergency powers during the health crisis and misused them to withdraw financial assistance from municipalities led by opposition parties. Later in the year, Hungary passed constitutional amendments that further strengthened executive power.

Hungary is the only EU member state not classified as Free.

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.