This has been a rough year for the countries of Central and Eastern Europe in terms of governance, with neighbours Poland and Ukraine seeing the biggest challenges.

In Poland, the ruling Law and Justice party (PiS in Polish) has attempted nothing less than an entire overhaul of the post-communist institutional order, a process which has sparked massive controversy and brought rebukes from the European Union. In next-door Ukraine, institutional reform is also underway but in a more beneficial direction. Here the country is attempting to emerge from underneath the corrupt post-communist edifice that was built by former Presidents Leonid Kuchma and Viktor Yanukovych and which remains a drain on growth.

However, Ukraine is facing its own challenges in overcoming this institutional inertia, not least of which is seven centuries of experience to the contrary. Indeed, as I argue in my latest book “Two Roads Diverge: The Transition Experience of Poland and Ukraine”, the economic outcomes of both Ukraine and Poland, over the past thousand years, can largely be explained by the institutional make-up of the two countries, especially in key institutions such as property rights, freedom to trade and an independent judiciary. It seems that, in terms of their histories, Poland and Ukraine are reverting to type today; what remains to be seen is whether history will remain their destiny.

Historically, there has been a constant struggle over the centuries, in Poland, between an executive which seeks to gather power for itself versus a myriad of decentralised actors who work against such an eventuality (in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, this role was played by the szlachta, or the Polish nobility). During times when this opposition did not exist, or when there was little counterbalance between the opposites of power, Poles saw their property rights corrupted, the rule of law weakened and a general economic malaise followed closely behind.

In some extreme cases, the desire to struggle against the overreaching sovereign weakened the country so much that external foes were able to benefit: the near-endless warfare of the 17th century led to Poland’s Partitions in the 18th century, while a military coup and a move towards proto-fascism, in the 1930s, eroded individual liberties and left the country ripe for the dual Nazi-Soviet invasion.

While the country is no longer in as dire circumstances as it was during either of these historical periods, the signs are not especially encouraging, particularly with an aggressive Russia on the move in Ukraine and Syria.

Within Poland, the elections of 2015 have left PiS with an unassailable majority in government; a majority they have used to push through reforms that have far-reaching consequences. In their rushing through of changes in the Constitutional Tribunal and their institution of taxes on financial institutions, the current government has created an atmosphere of economic uncertainty, as well as assaulting property rights.

However, the government finally saw some pushback against its overreach in the past week, as the proposed draconian anti-abortion laws were defeated in parliament after a one-day strike by Polish women and broad-based protests throughout the country. But the lack of people on the streets to protest other moves against banks, supermarkets and the overall rule of law show that there still is not an effective or consistent counterbalance to the PiS government.

In contrast to Poland, there has never been a tradition of decentralisation in Ukraine, with both the political and economic systems being highly concentrated on whomever was in power at the time. Throughout its history, Ukraine’s internal institutions have always favoured the state, at the expense of the individual, with a large (if not necessarily well-developed) bureaucracy administering the whims of the ruler.

In modern times, this institutional make-up has been heavily influenced by Russian ideas of administration, but it predates even the absorption of Ukraine into the Russian Empire in the early 18th century. Even during its brief period of independence, in the mid-17th century after the revolt against the Polish monarchy, the ruling Cossacks made it clear that they wanted to replace the dictatorship of the Poles with an indigenous dictatorship made up of themselves and that they would be charged with overseeing all facets of the nation’s life.

Of course, one need not look back, as far as the 16th century, to see the source of Ukraine’s current problems, as the post-communist crony state that the Maidan Revolution sought to dismantle was a direct design of former President, Leonid Kuchma, perfected by his protégé, Viktor Yanukovych, from 2010 to 2014.

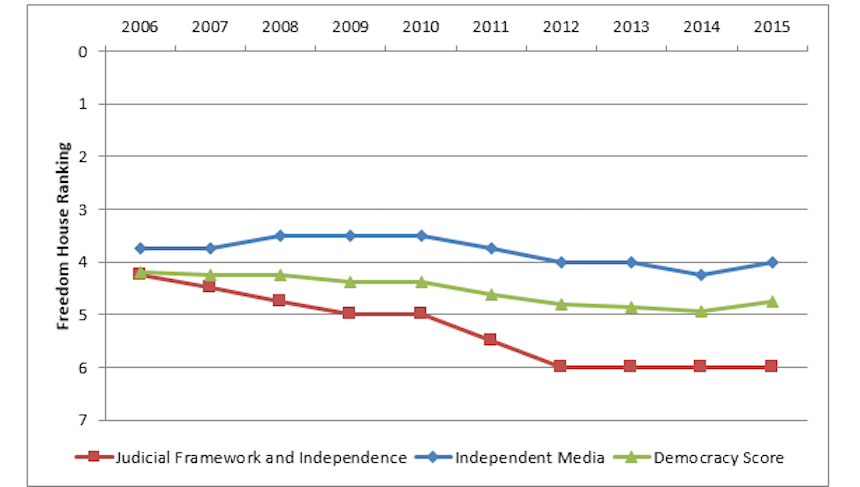

Indeed, the decline in democracy and the freedom of the judiciary, under Yanukovych, was pronounced, as shown in the figure below. With such an assault on the basic institutions of a country, even those beginning from an already-low level, economic outcomes were sure to be impacted. In fact, the emphasis on state involvement, in every aspect of the economy, encouraged rent-seeking and corruption as a matter of course; a reality that Ukraine is finding very difficult to break away from.

Nearly three full years after protests began in Kyiv, and two and a half years after Maidan, despite making great strides, since 2014, many of the promises of the revolution remain unfulfilled and the window of time for reform is closing rapidly.

Whether or not this long history of institutional development is indeed the destiny of both Ukraine and Poland remains to be seen. In fact, Poland has fared much better than Ukraine for most of its existence, in terms of its economic development; a testament to its ability to survive institutional deterioration. On the other hand, Ukraine has been handicapped by the non-existence, or denial, of the basic institutions necessary for a market economy (most of all, property rights), and has only recently begun to attempt to rectify this omission.

What is unnerving about recent developments is that Poland appears to be entering an institutional downturn, just as Ukraine is struggling to recover from the Yanukovych years and a concomitant Russian invasion in its east. Whereas Ukraine is reaching to Europe for assistance and to build its future, the new Polish government is looking increasingly inward (or even to the very model of a crony state, Viktor Orban’s Hungary).

While institutional development may be the culprit for centuries of economic divergence between Poland and Ukraine, Poland’s recent institutional changes could be forcing a convergence with Ukraine that is not for the better. That has huge consequences for the future of Europe in general.

The transition experience of Poland and Ukraine will be discussed, in its many perspectives and dimensions, during the discussion panel ‘Ukraine, Poland, and Divergence in Transition‘ at the CASE 25 Anniversary Conference The Future of Europe, which will be held on 17-18 November, 2016 in Warsaw, Poland. Emerging Europe is a media partner of the Conference. Click here to register for the Conference.

_______________

The views expressed in this opinion editorial are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Emerging Europe’s editorial policy.