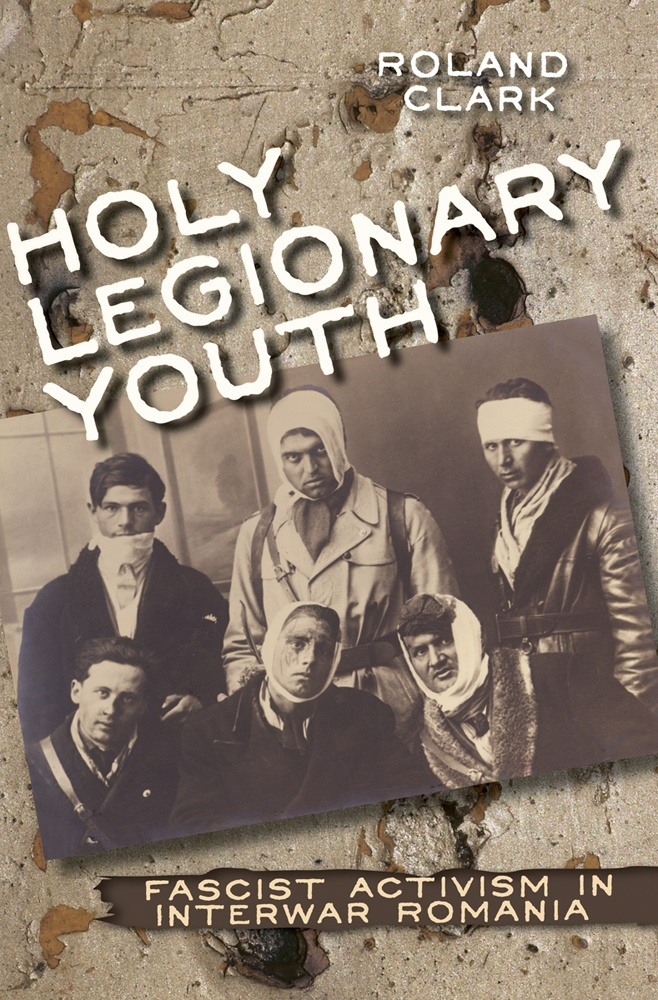

Holy Legionary Youth: Fascist Activism in Interwar Romania, by Roland Clark

The next time anyone tries to convince you that the Romanian Legionary Movement of the 1930s and early 1940s was anything other than evil it is enough to remember just one passage describing the Bucharest pogrom of January 1941 from this quite brilliant book:

Legionaries began arresting Jews on 20 January, and the following afternoon gangs of legionaries invaded Bucharest’s two largest Jewish neighbourhoods. They loaded roughly two thousand Jews – including children and the elderly – onto trucks and transported them to prearranged sites where they beat, raped and tortured them. Of the legionaries involved in torturing Jews at the police station on Matei Basarab Street, most were aged between 15 and 25 years old.

Despite such horrors there is an increasingly vocal minority of people in Romania attempting to rehabilitate the legionaries, emphasising the suffering endured by many of them at the end of World War II, when they were imprisoned. Some have gone so far as to propose their canonisation, calling them Christian martyrs. Read Roland Clark’s book and you will be left in no doubt as to whether or not these thugs were saints.

They were not, in the first place, Christian. Though legionary dogma contained certain mystical elements and its practices (and name) borrowed from Eastern Orthodoxy, the Legion was a death cult which resembled the secular Nazi SS far more than a religious movement. Plenty of Orthodox priests condemned the Legion. The monks at Putna Monastery in Bucovina went so far as to refuse to bless their flags and other paraphernalia. Indeed, as the author explains, the legionaries did not view themselves as being particularly religious. The narrative that they were ‘good Christian boys doing God’s work’ only appears much later, after many had rotted away in prison.

Boys, however, they certainly were. The Legion’s membership was made up primarily of very young, physically impressive, racially pure though often poorly educated youths: almost exclusively male. Just like the Nazis, the Legion had little time for the frail, the physically impaired or the disabled. The Legion was fixated by muscular masculinity and the idea of creating a ‘new Romanian man’ (something with which Nicolae Ceausescu would later become equally obsessed). ‘Work camps’ were organised at which strenuous physical exercise, generally done in very little clothing, was ever present but women seldom were.

While Clark makes it clear that some of these young men were manipulated by their leaders into committing acts of violence he goes too far in our opinion towards using their naïveté as an excuse for their barbarism. It is a moot point of course, and is just about the only fault we could find. Holy Legionary Youth is packed with detail, impeccably documented and – given its academic provenance – thoroughly readable. Published almost three years ago the book had been off my radar until I was sent a link to a podcast interview with the author himself. If your interest in the subject does not stretch to the 32 UK pounds for the book itself (even the Kindle version costs over 20 UK pounds), then the podcast is well worth a listen, as Clark talks at length about many of its main themes.

Romania’s infamous Legion of the Archangel Michael grew out of various anti-Semitic, anti-foreigner political movements which appeared in the aftermath of World War I. The charm of Queen Marie had managed to more than double Romania’s size at the Treaty of Versailles, and as a result various nationalities, from Ruthenians and Ukrainians to Hungarians and Saxons had to be incorporated into what had hitherto been a far more homogeneous country. All were targeted at some stage, but it was the Jews who bore the brunt of the fascist movement’s discourse and attacks, beginning with the chaotic student protests of 1922 and ending in the pogroms of the 1940s.

The Legion spent much of the early 1930s roaming Romania’s cities attacking anyone they disapproved of, primarily (but not only) Jews. They found such things amusing. Like many young men from all over the world, some even went to Spain: not to fight for freedom and the Spanish republic however, but to fight with Franco. The dead were then given state-like funerals when their bodies were returned.

The Legion was led by Corneliu Zelea-Codreanu (the central figure in the main photo at the top of the page): a vicious murderer with a messianic-complex who saw violence not merely as a means of achieving political goals, but also as something that would boost the masculinity of those who perpetrated it. On his wedding day he and his wife wore crowns emblazoned with swastikas.

As the 1930s progressed Codreanu’s disciples terrorised large swathes of the Romanian population, carrying out political assassinations and murder with impunity. And as Clark is not slow to point out, they did so with much popular support, both from the peasantry and from intellectuals who really ought to have known better. Emil Cioran and Mircea Eliade were just two of the astute minds seduced by the Legion. To his eternal credit, Cioran spent much of the latter part of his life genuinely remorseful and deeply ashamed of his earlier fascist sympathies. Eliade’s attitude towards the Legion was always far more ambiguous.

Some intellectuals went beyond merely sympathising with the upstart political movement of the day. Radu Gyr, a poet, was an active legionary who led one of its notorious death squads. Last year a clothing company, Legende Vii, was forced to withdraw from sale a t-shirt emblazoned with Gyr’s portrait following protests from Romania’s Holocaust Studies Institute.

Codreanu led the Legion with an iron fist and central control over the membership was tight. All new recruits had to read his atrocious writings. Dissent was not tolerated and legionaries who stepped out of line were severely dealt with, sometimes even murdered. So obsessed with discipline was Codreanu that he even issued a decree dictating how legionaries spent their free time (in the service of the Legion, of course). The word cult barely existed in the 1930s, at least not with its current meaning. But there is little doubt that’s what the Legion was.

Though Codreanu himself was fortunately killed by Bucharest police in 1938 (if ever there was a sound case for extra-judicial killing, this was it) the movement did not die with him. In partnership with Codreanu’s father Ion (until they later fell-out), the leadership was assumed by Horia Sima and, if anything, the Legion became even more violent. From September 1940 to January 1941 it briefly ran the country, until Marshal Ion Antonescu, Romania’s wartime military dictator and himself no angel, could no longer tolerate the Legion’s violence. It survived in exile (Sima went first to Germany and ended up in Franco’s Spain), although many of its foot soldiers were imprisoned. Others became communists.

It is hard not to make the obvious comparison between the violent, peasant-student movement of early 1920s Romania (which begat the Legion) and the Red Guards of late 1960s China. Both sets of students were appallingly educated (barely literate in some cases) intent not just on usurping their elders but utterly destroying them. The Legion’s ideology, not fully developed until the mid-1930s, placed great emphasis on the need for the individual to wholly submit to the collective. It is no wonder so many former legionaries found communism attractive.

Finally, it is important to note how similar legionary ideas are to those of today’s Romanian ultra-nationalists. The threads which ran through legionary dogma: Jews/foreigners/women-with-ideas-above-their-station are preventing us from becoming a great people/country; the modern world is evil; they are colonising us and destroying our culture and traditions; only sacrifice, blind obedience and a return to reactionary values can save us; are there for all to see in the rantings of the neo-Legionaries.

Fortunately, today’s Romanian youth is much different to its 1930s equivalent. Hedonistic, well-read, well-traveled, open-minded and increasingly wealthy, these are not the shock troops of a legionary revival. The pleadings of today’s fascists are thankfully falling on deaf ears. The failure of last weekend’s constitutional referendum was proof of that.

—

Main photo: Wikipedia/Public Domain