Brexit negotiations started in Brussels on June 19, almost exactly a year after the UK’s vote to leave the EU.

The EU27 side has made it clear that “substantial progress” must be made on two key issues — the so-called “divorce bill” that the UK has to pay, and the status of EU citizens post-Brexit — before talks on a future trade relationship can begin. A third issue — the border between Ireland and Northern Ireland — is unlikely to be resolved until later in the talks, despite some press reports that this was a further condition of the EU27, before trade negotiations begin. This was always unrealistic; until a decision is made on whether or not the UK will leave the Customs Union, for example, a serious discussion on the Ireland-UK border is impossible.

There is a lot riding on these negotiations, for the Central and Eastern European countries, which are members of the European Union (EU-CEE). Although France and Germany are likely to take the lead in steering the EU27 side, potentially EU-CEE countries have a lot to lose if talks break down. Five aspects of the negotiations are particularly important for EU-CEE.

Status of workers already in UK

Both sides appear keen to strike a deal on the status of EU27 citizens in the UK and vice versa, although in recent months there have been indications that the UK side is underprepared and unwilling to acknowledge the complexities. A key sticking point will be if and how the European Court of Justice (ECJ) can enforce the rights of EU27 citizens in the UK post-Brexit. One of Prime Minister Theresa May’s red lines, before the recent election, was ending ECJ Jurisdiction In The UK.

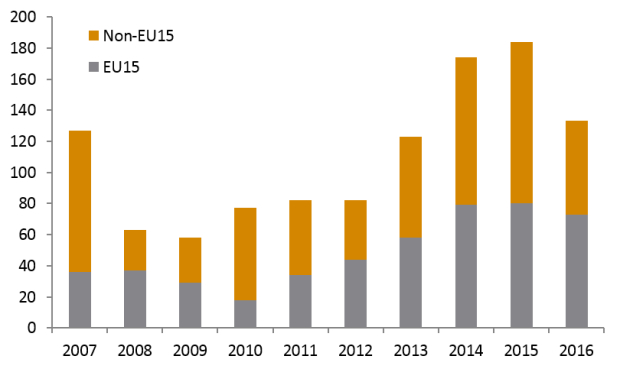

From the EU-CEE perspective, this matters a lot. Around 3.3 million EU27 citizens are estimated to be living in the UK, of which around 1.6 million are from EU-CEE. Since 2007, net immigration to the UK, from EU member states that joined in 2004 or later, has averaged 62,000 per year, and the number reached around 100,000 in 2014 and 2015.

It is highly unlikely that EU-CEE citizens in the UK will have to leave after Brexit (although many may choose to because of expected weaker economic conditions). However, in the unlikely event that a mass exodus occurs, it clearly would be disruptive for EU-CEE countries if most decided to return home (they could of course go to other Western European countries).

Future migration controls

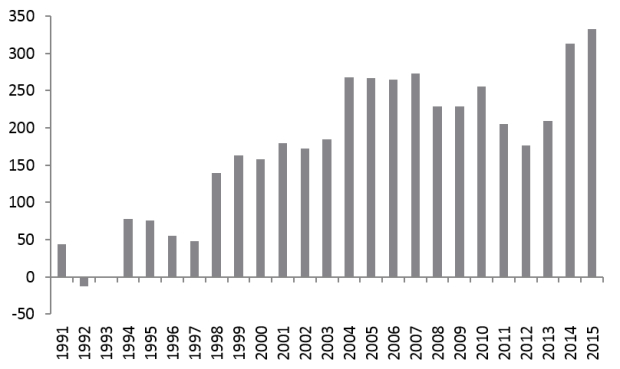

A deal on future migration is likely to be a much more difficult part of the negotiations, and conditions on this will be linked to the terms of the future trade deal. Brexit was about many things, but the large spike in net immigration to the UK in the past 20 years was probably the single biggest reason (most of this was not from the EU, but that is by the way).

Nevertheless, reality appears to be dawning in London that the UK economy is far too reliant on workers from EU-CEE to bring the numbers down significantly. The number of applications by nurses from the EU, for positions in the UK’s National Health Service, has fallen by 96 per cent since the Brexit vote.

One cannot generalise completely, but workers from the EU tend to be young, in work, and net payers into the tax and social security systems. Cutting this off would be quite drastic and would have a material impact on the UK’s economy and living standards. Therefore some kind of fudge is likely. “Taking back control” — a key message of the campaign in favour of Brexit – may end up meaning simply having the right to stop EU migration, but not actually exercising this right to any significant degree.

EU funds inflows

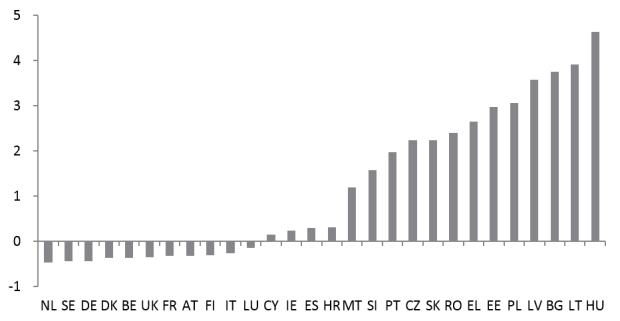

This is one of the most important issues for EU-CEE in the Brexit negotiations. Net EU funds inflows are equivalent to two-five per cent of GDP, per year, for most EU-CEE countries and the UK contributes slightly less than one fifth of this. The EU 27 will attempt to ensure that the UK pays a hefty “divorce bill”, to ensure that these funds continue to flow for at least the rest of the current financial period (officially up to 2020, but in practice for another couple of years after that).

The right-wing of the Conservative Party and many influential sections of the UK media will not accept this easily (it jars badly with the leave campaign’s promise that Brexit would result in a net gain of £350 million per week for the UK), which will reduce the UK government’s room for compromise.

Whatever the outcome, it looks likely that there will be a hole in the EU budget, at least from 2020 onwards. It is possible, but highly unlikely, that this will be filled by other wealthy member states. France’s new president, Emmanuel Macron, has made clear his frustration with parts of EU-CEE over various issues.

However, more quietly, other Western leaders are also irritated by the unwillingness of parts of EU-CEE to participate in refugee sharing, among other sources of friction. Therefore, EU funds inflows relative to GDP are likely to be smaller for EU-CEE in the future, removing an important contributor to growth and a crucial source of funds for public infrastructure investment in particular.

A new trading relationship

The terms of a future trade deal between the UK and the EU27 are the most difficult to gauge at this stage. They could be anything from basically the status quo (which is highly unlikely) to a so-called “hard” Brexit and recourse to World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules (this is also unlikely, but more probable than a continuation of the status quo).

There are many possibilities in between, but working on the assumption that the UK will leave both the Single Market and the Customs Union (the current situation indicates that this is the most likely scenario, but such has been the volatility of UK politics in the past two years that this could change), the deal is likely to be free trade in goods, plus some in services (with significant restrictions relative to the current set-up).

Whatever deal is eventually agreed on passporting rights, some firms in the financial sector will move their operations away from London. However, the beneficiaries of this are likely to be countries in Western Europe such as Ireland and Germany; the implications for EU-CEE should be minimal.

Our studies indicate that nowhere in EU-CEE are value-added exports to the UK particularly significant relative to GDP. Such exports range from 2.1 per cent of GDP in the Czech Republic to 0.8 per cent in Croatia (the EU-CEE average is 1.6 per cent). On services, the relationship is even weaker; total services exports from EU-CEE to the UK in 2015 ranged from 1.3 per cent of GDP in Croatia to 0.2 per cent in Estonia according to Eurostat data. Therefore, even a fairly drastic disruption of trade between the UK and EU27 would not be a disaster for the region.

However, European value chains are increasingly complex, often involving inputs from several countries, and relying on “just in time” manufacturing. Services exports from the UK are also key in many parts of the European economy. While restrictions may create opportunities for EU-CEE further down the line, as firms leave the UK to remain inside the Customs Union and Single Market, in the next few years this could be disruptive for EU-CEE countries.

Security cooperation

France and the UK are the only serious military powers in the EU. Unlike France, hawkishness towards Russia is fairly broadly-based in the UK and, as a result, its continued support on security issues is seen as vital by Poland and the Baltic states (attitudes towards Russia are more mixed, if not outright positive, in much of the rest of EU-CEE). The UK is also a key part of NATO and this commitment is not in question.

Only a catastrophic and acrimonious breakdown in Brexit negotiations would create the possibility of UK commitment to security in EU-CEE being threatened, and even in that scenario it would be unlikely.

_______________

The views expressed in this opinion editorial are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Emerging Europe’s editorial policy.

The editorial is an edited version of the article published on the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies website.

Add Comment