The assertive and ambitious leader of the ‘People’s Republic’s fifth generation of leadership’ and charismatic president, Xi Jinping (in power since the end of 2012) is attracting worldwide attention. However, because we are quite a distance from China, mixed unfortunately with a lack of strategic thinking and a certain neglect of the ‘emerging markets’ phenomenon on the European side, our understanding of the strategic impact of a China’s new role remains below expectations and needs.

This is also visible in the Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) countries, even if the previous Chinese leadership (of the Fourth Generation) already came out with a new blueprint for their relationship with the region, in the form of the then-famous 12 steps, which was proposed by Prime Minister, Wen Jiabao, in Warsaw, in April 2012. Not much was implemented from this ambitious plan – to inaugurate stronger economic ties – but at least, since then, we have a new framework of cooperation known as 16+1, with its own Secretariat and annual summit meetings.

Even the flagship of this new cooperation — a high-speed Chinese bullet-train route from Belgrade to Budapest, which was announced with some excitement at the third Summit in 2014 – is not ready to start and the European Commission has expressed some doubt concerning the transparency of the deal, with its latest concerns being expressed in February this year.

Nevertheless, and not taking into account such obstacles and complications, China is pushing forward – especially after the inauguration of another ambitious strategic project in late 2013; the visionary One Belt, One Road (OBOR). It is supported by an institutional framework and includes a special OBOR Fund. It is ‘Asian’ by name but Chinese by money and design and the funding comes from the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). Thus, another important stimulus was added to the growing and ever-rich agenda of China-CEE cooperation.

The crucial problem is that, as in the EU, almost all the countries of the CEE region didn’t prepare or present their own blueprints and strategy for China. Only Hungary under the leadership of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán – also a strong and charismatic leader (although controversial in the EU) – has announced its own ‘keleti nyitás’ meaning ‘Opening to the East policy’. Results, up until now, have been disappointing and even foreign minister, Péter Szijártó, has publicly confessed, as late as last year that almost nothing from this strategy was implemented, least of all the 350 km of Chinese high-speed railway to Belgrade.

There is an array of difficulties and obstacles: we start from different business mentalities on both sides – we believe in institutions, rules and regulations, including public procurements and the Chinese believe in personal relations, mutual trust and win-win strategy, etc. Despite this, Hungar is pressing for further cooperation. In December 2016, a first step in the bilateral cooperation for OBOR was taken in Beijing, with Szijártó and his counterpart, Wang Yi’s signatures, and earlier this year Hungary joined Poland to be the second country from the CEE region to be represented in the AIIB.

Budapest is ready to give two-year long visas to Chinese businessmen (others in the region are usually given around 90 days), and it is also expanding its programme of settlement for Chinese citizens (although it is not directly transparent: this will cost some 300-350 thousand Euro). It is not a coincidence then, that Hungary is emerging as a leading trade and investment partner for China in the region (true – Poland has replaced it in last two years, but no one knows for how long), and — on the other hand — it is also no surprise that a special think-tank network was just established in Budapest, on April 24th, with a prominent role being taken by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing’s Institute of European Studies that published recently a series of important volumes (both in English and Chinese) on bilateral relationship with the CEE region.

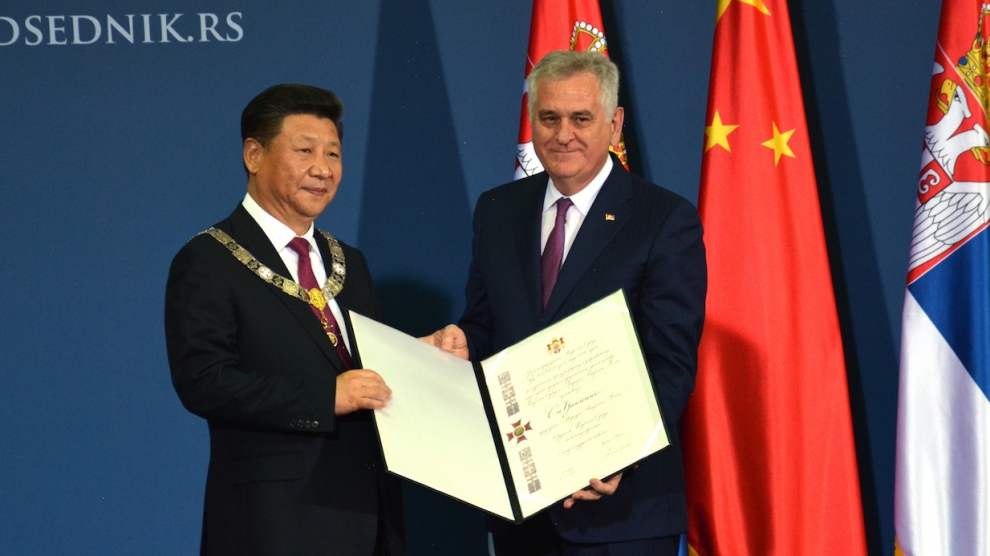

From reading those publications, as well as the official announcements, we know that Poland will be a crucial partner for the Chinese because of its geopolitical position and location between Russia and Germany (this was once a curse historically, but now it is an advantage from the Chinese perspective). Poland also has the biggest economic potential in the region. This was confirmed by the visit of President Xi Jinping to Warsaw in June 2016, when the bilateral relationship was upgraded to the highest possible level, i.e. a comprehensive strategic partnership.

However, as we now see, not too many of the agreements that were signed were implemented, and the creation of a regional communication hub in the town of Łódź – very important in the Chinese plans — has been postponed. The Polish Minister of Defence decided not to allow the military territory, which belonged to the army, to be given over for new Chinese investments. However, the Chinese response is significant and pragmatic — if we cannot manage with the government, we will turn towards the alternative government (in the opposition’s hands mainly), who are usually more eager to cooperate or invest. So, plans for the railway hub have shifted, recently, from Łódź to nearby Kutno and we can identify one local investment after the other beginning to take shape: after earlier investments in the steel works in Stalowa Wola or the rolling bearing factory in Kraśnik, we saw fusion and mergers with the Nuctech company (medical equipment), movement in the energy sector in Gdańsk (Piinggao Group) or Lublin (Sinohydro), and electronics in Żyrardów or plastic goods in Tarnów.

As for Western Europe, which is the main direction of the new Chinese investment fever (some $170 billion in 2016, as much as 44 per cent more than a year earlier) the Chinese are eager to get some trademarks established, which is not necessarily what the CEE partners expected. For instance, in Romania, only one greenfield project coming from Chinese investment was inaugurated, in the port city of Constanța. All the other investments are fusions with existing industry or companies (such as air terminals, sea ports, etc.).

So, instead of a having a normal trade in goods, we in the CEE region have almost all the Chinese banks here already; we have new investment projects and visible activity. It is time to wake up and to respond in a more inclusive way to this new phenomenon.

Participation in the upcoming first Summit meeting of OBOR, scheduled for mid-May is probably is not enough, even at Prime Ministerial level, as in the case of Poland, the Czech Republic or Hungary. We should have our own think tanks and our own ideas about what to do with the new Chinese initiatives. Especially given that the lack of trust and mutual knowledge remains the main obstacle in this constantly growing exchange.

But what are the Chinese’s expectations? We’d better be ready, because a dragon is knocking at our doors!

____________________

The views expressed in this opinion editorial are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Emerging Europe’s editorial policy.