In some countries, when their leaders have egregiously over-stepped their authority to shield themselves from accountability, citizens have taken to the streets with some success.

Corruption and impunity ignite public protest. Anger against corruption sparked the Arab Spring, it also forced Ukraine’s former president Victor Yanukovych to flee and more recently brought tens of thousands onto the streets of Bucharest in Romania (in the picture). Citizens want leaders who work in their interests. However, even when the message is delivered en masse the day-to-day task of fighting corruption is never easy.

The successes and failures of the emerging European economies offer some reasons for hope but also reveal too many cases where powerful elites have co-opted the levers of power. This is true from the Balkans via the Bosporus to the Baltic. Strong institutions – the core of any anti-corruption programme — do not emerge fully-formed overnight, particularly in places that have lived through decades of single-party rule. Two decades on, there is still much work to be done and progress is under threat.

Successes and failures

Although some emerging economies have been more successful than others in building public institutions and empowering independent agencies that are fit for the purpose of taking on the corrupt, in many countries, such accountability systems have not yet emerged. In addition, solid independent media and a strong civil society are far from well-established and, with the lurch towards a new era of populism and authoritarianism taking hold, they may never get the chance.

The voices that speak truth to power too often find themselves behind bars. Russia and Turkey come to mind immediately.

The will was there in the beginning. Since the early 1990s, and with the ever-increasing prospect of enlarging the European Union that followed the collapse of the Soviet bloc, many of the post-Cold War emerging economies did take steps to develop and strengthen their anti-corruption systems. However, in a context of economic turmoil and persistent social fragmentation, the conditions for favouritism and an uneven application of the law still thrive. The end result is a situation where laws and anti-corruption policies, while good on paper, are selectively enforced and corruption in public office goes largely unsanctioned.

Lack of a serious approach

A consistent feature, across the emerging economies in Europe, and one which is blocking improvements in spite of better legislation is the phenomenon of state capture – whereby powerful executive branches and political parties dominate all the other institutions. This, coupled with a lack of cooperation and coordination among state actors, has undermined the ability of supposedly independent judicial, law enforcement and anti-corruption bodies to provide a meaningful oversight of government activities and to investigate and prosecute corruption effectively.

Emerging institutions are vulnerable to state capture, as has been the case in Hungary, for example, within the democratic context. Politicians with an authoritarian bent are quick to use corruption, which they link to social inequality, as a reason for insisting on more powers. The problem is that they usually have no intention of tackling corruption seriously: the track record of populist leaders fighting corruption is dismal because the concentration of power itself has never led to increased oversight or more fairness.

In some countries, when their leaders have egregiously over-stepped their authority to shield themselves from accountability, citizens have taken to the streets with some success. We saw that in Romania recently. However, there are also cases in Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia where powerful people have gotten off the hook for corruption because of their connections and a lack of will to apply the law without favouritism. Indictments are often poorly written and inadequately investigated and complex corruption cases are poorly understood by prosecutors and judges. We have seen this in Albania and Kosovo, also.

Judicial independence

Despite this bleak picture, there have been some important attempts to strengthen the independence of institutions, particularly the judiciary in some countries, demonstrating that, where the political will exists, reform is possible. There is a common understanding of what has to be done to combat corruption.

Montenegro, for example, is planning to introduce the principle of the immovability of judges. It has placed limits on the political influence over the process of appointing judges and has improved cooperation between the prosecution and the police by providing the grounds for the establishment of a special investigation team, when it is deemed necessary. We wait to see this in practice. Kosovo has given judicial and prosecutorial councils greater discretion in drafting and proposing their budgets and the judiciary has a more prominent role in appointing members to the judicial council, but it remains to be seen how these will work. The Georgian judiciary is showing signs of becoming more impartial in its decisions and more active in holding the government to account.

However, in the cases of Azerbaijan and Ukraine, corruption prosecutions tend to be either politically motivated or to target petty offences and those who oppose the government. In Armenia, the number of corruption prosecutions is limited. Moldova’s much needed judicial reforms are lagging behind and are perceived to be highly politicised.

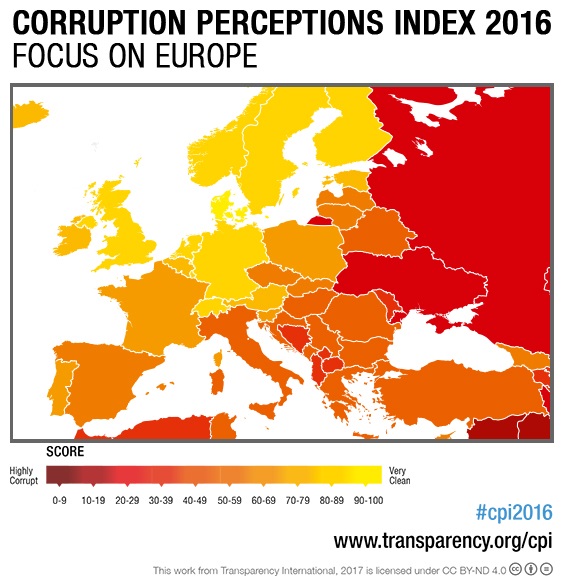

Perceptions of corruption: no change

There were few changes in Europe and Central Asia in the Corruption Perceptions Index 2016, which given the problems mentioned above is not a good sign. High-profile scandals associated with corruption, misuse of public funds or unethical behaviour by politicians, in recent years, has contributed to public discontent and mistrust of the political system.

The Ukraine’s minor improvement this year probably benefitted from the launch of the e-declaration system that allows Ukrainians to see the assets of politicians and senior civil servants, including those of the president. Still, important cases of Grand Corruption against former president Yanukovych and his cronies are currently stalled because of systemic problems in the judicial system.

As stated above, the capture of political decision-making remains one of the most pervasive and widespread forms of political corruption across emerging economies and the rise of populism will do nothing to stop this. Companies, networks and individuals unduly influence laws and institutions to shape policies, and the legal environment and the wider economy to their own interests. That is why it is so important for civil society to be strengthened and for the media to remain free and independent. The promise of a democracy that delivers strong institutions — something that was considered a given in the heady days of the 1990s – is far from certain, though it can be achieved as long as citizens do act in defence of democratic principles and hold their leaders accountable.