The sheer speed, scope and impact of technological change are challenging the businesses – and society at large – in fundamental ways. So how do we ensure CEE continues to provide a steady stream of digital talent?

In the small town of Iłża, about 150 kilometres from Warsaw, the capital city of Poland, a group of four teenagers from a local high school are working on a device to make learning easier for visually impaired children.

The device will use an OCR (Optical Character Recognition) technique and will be very small so the students will be able to attach it to their glasses and hear the contents of their school textbooks.

The project, developed by Maksymilian, Agnieszka, Mikołaj and Piotr, impressed the jury and won this year’s edition of the Tech Minds grant competition, organised by PwC Poland. The goal of the competition is to promote and reward digital talent and teamwork.

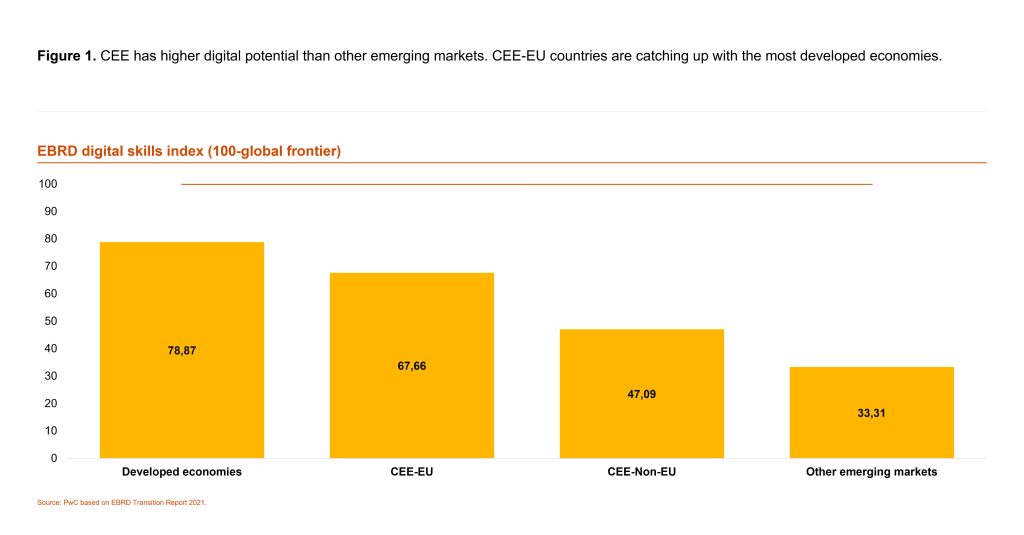

There are many more digitally savvy and ambitious young people, like the teenagers from Iłża, in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). And talent is right at the heart of any discussion about the future of our region. CEE countries have a large and agile talent pool of more than two million tech specialists. The region also has a strong STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) tradition with many tech universities. And according to the EBRD digital skills index, CEE has higher digital potential than other emerging markets.

Still, according to our 26th Annual Global CEO Survey, executives in our region say that potential shortages of labour and skills are the top threat to their business – part of the ongoing global war for talent that has been evident in CEO surveys for several years now.

When asked about the forces most likely to impact their industry’s profitability over the next 10 years, as many as 64 per cent of regional CEOs cited skills shortages as impacting them “to a large/very large extent”, well above the 52 per cent global rate.

The sheer speed, scope and impact of technological change are challenging the businesses – and society at large – in fundamental ways. So how do we ensure CEE continues to provide a steady stream of digital talent?

Providing education that will give students skills required by employers

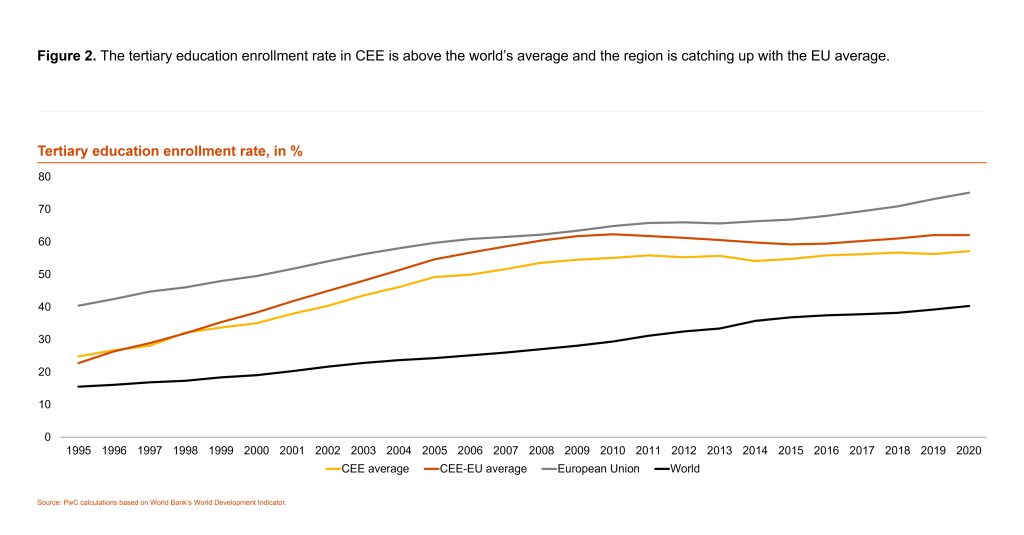

Since the 1990s, CEE has improved significantly in terms of quality of education and access to it. When it comes to tertiary education enrolment rates, the region is above the world’s average and is catching up with the EU average.

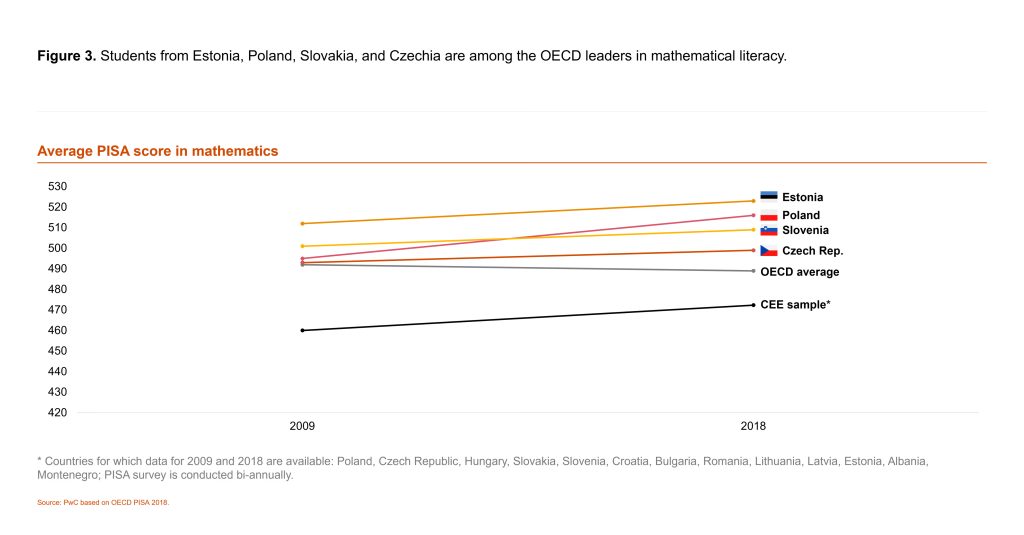

What’s more, CEE is expanding the right talent pool to fuel the growth of digital and tech businesses. Teenagers from the Czech Republic, Estonia, Poland and Slovenia are among the OECD leaders in mathematical literacy. In 2021, there were more than 435,000 ICT (Information and communication technologies, a core element of STEM) students in the region (about 43,000 more than in 2017).

While progress is being made across CEE, the region still needs to catch up with the EU average when it comes to the number of STEM graduates.

How to do it? The national governments should invest more in school curricula and learning materials so teenagers and students will be able to improve their digital skills. EU member states in the region have access to numerous funds that allow them to extend their digital resources. For example, the European Commission dedicated 127 billion euros to digital related reforms and investments in the national Recovery and Resilience Plans.

According to a recent EU Digital Economy and Society Index report, countries dedicated on average 26 per cent of their Recovery and Resilience Facilities allocation to digital transformation, above the compulsory 20 per cent threshold. Around 17 per cent of the expenditure dedicated to digital objectives (22 billion euros), is devoted to digital skills development. Slovakia, for example, will update school curricula and learning materials to include digital skills and teach computational thinking.

My home country of Croatia, in turn, supports the digitalisation of higher education through investing in e-learning and digital teaching tools. Apart from that, there are many local private initiatives whose goal is to empower all children in the country to develop their STEM competencies.

Governments, public and private institutions should also encourage more girls to study STEM to enlarge the region’s digital talent pool. I’ll return to that in a moment.

Improved STEM skills will be very important in allowing students to enter the job market and take high-level technology jobs. Yet the education systems will only be sustainable if they are more responsive to market needs and give students all skills required by employers. Soft skills are also important in making young people adaptable and employable throughout their working lives. Some CEE universities have already taken actions and designed new methodologies for their curriculum, which allow students to acquire and improve, among others, cooperation, communication, critical thinking, leadership and problem solving skills that prepare them for real life professional challenges.

Just to give you one example: PwC designed a new curriculum for the Audi Hungaria Faculty of Automotive Engineering at the Széchenyi István University (Győr, Hungary) that consists of only cooperative projects. This innovative curriculum requires students to work in teams to solve consecutive engineering challenges (projects). Each individual is responsible for a dedicated subtask but also must collaborate to ensure the overall success of the team. Traditional lectures are replaced by small, targeted “learning molecules” that provide the knowledge required for solving the engineering project at hand.

The reformed programme prepares students to play an active role in society and become the driving force in the local and wider economy. The new methodology has also the potential to be extended to additional programs at the university in the future.

Upskilling employees and society

PwC’s research shows that one in three jobs is likely to be severely disrupted or to disappear by mid 2030s because of technological change.

In the CEE region this share is even higher: in Slovakia – 44 per cent, Slovenia – 42 per cent, Lithuania – 42 per cent, the Czech Republic – 40 per cent, and Poland – 33 per cent. Moreover, our Hopes and Fears Survey revealed that 39 per cent of workers are concerned that their job will be obsolete within five years, with 60 per cent worried that automation is putting many jobs at risk. But at the same time, 77 per cent of that same group are eager to learn new skills or completely retrain, with skills that transcend the technical, such as team management, critical thinking, and problem-solving.

Thus, the solution for finding the right talent can come from what’s already available within an organisation. By investing in their own people, governments and companies can increase the overall availability of tech skills and widen the talent pool. The good news is that according to our recently published 26th Annual Global CEO Survey, 65 per cent of CEE business leaders are planning to invest more in upskilling their workforce in priority areas in the next 12 months.

PwC is also working with many clients to help them upskill employees and the society at large. One of the examples is the project conducted for the Polish Chancellery of the Prime Minister. This project, funded by the European Union, aims to raise digital skills among various groups – from preschool children, pupils, students, professionally active people, to the elderly and digitally excluded. It involves various types of educational and information initiatives.

There are also many opportunities to create new talent pools to fill the gaps. As ways of working continue to evolve, organisations should increasingly consider recruiting from underrepresented groups, including people with disabilities, part-time workers, individuals based in remote areas or overseas, workforce returnees, and women.

Hiring more women in tech

According to Eurostat, there is still a persistent gender gap: eight out of 10 ICT specialists across the European Union are men. The proportion of female ICT specialists in some CEE countries is significantly higher than the EU average (19.1 per cent). For example, in Bulgaria, 28 per cent of ICT specialists are women, in Romania – 26 per cent. Yet, companies and governments should do more to invite more women to the world of technology. And this is not just to enlarge the talent pool.

Numerous studies show that the participation of both men and women in the workforce is essential for the viability of businesses and economies. Mixed teams generate solutions that are more creative, with evidence showing strong links between gender diversity, collective intelligence and team performance. What’s more, if technology is primarily designed by just half of the population, users are missing out on the insights, innovations, and solutions of the other half.

But how to engage more women? As I mentioned earlier, we need to start by improving our education systems. PwC’s research confirms that the gender bias starts in school and carries on through every stage of girls’ and women’s lives. Both before university and at university, more boys than girls are studying STEM subjects. Despite exciting opportunities, girls aren’t considering technology as a career – partly because nobody is putting it forward as a possible option.

What we also heard during our interviews with women was that they didn’t want to work in technology because they didn’t want to be in a male dominated environment. This means that companies should be more committed to attracting and retaining women technologists at every level by creating a more inclusive and diverse environment in practice and not only in the pages of their corporate reports.

Today, technology is permeating every aspect of society and every function within organisations. Yet we can’t forget that the most important ingredient for technology success is people. Nobody knows this better than PwC. We are a community of solvers that uses technology to help solve complex business challenges, free up human power and identify new opportunities for ourselves, our clients and our communities.

Upskilling and expanding the pools of technology-savvy employees is no longer a minor thing that companies and governments do on the occasion of other projects and programmes. It will determine whether or not a company, a country and the whole CEE region will grow and remain competitive.

This article is part of Digital Future of CEE, a regional discussion series, powered by Emerging Europe, Microsoft and PwC.

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.