Back when I was at high school – long before supply teaching became a profession – the absence of a teacher would require a class to spend a lesson or two in the school library.

Ostensibly, such library time was meant to be put to good use, either doing homework or reading. In practice, my group of friends would find a distant table and do very little except talk football and generally mess around.

Despite being a fairly ordinary London comprehensive, the school in question, Raynes Park High for Boys, boasted a rather splendid library both in terms of the volumes it stocked and the vast space allocated to it. The librarian was the fierce Mr McGuinness. He doubled as the deputy headmaster and sent a shiver down the spine of most pupils.

One afternoon, when the absence of a maths teacher meant that we were once again confined to the library, we had as usual stationed ourselves at a table as far away from Mr McGuinness as possible and were predictably doing nothing constructive. Probably making far too much noise, Mr McGuinness began making for our table at great pace. Having learnt to always be two steps ahead, I had a maths textbook open in front of me and was quickly able to adopt a pose that suggested earnest study. One of our group, Tony Duggan, was less fortunate: all of his textbooks were in his rucksack, hidden under the table.

Thinking quickly, he reached behind grabbed the first book from the library’s shelves that came to hand. He just about managed to open it before Mr McGuinness appeared menacingly at our table.

What are you lot up to? He demanded to know.

Doing homework, some of us said. Reading, said others.

What book’s that your reading? He asked Tony.

Tony had no idea. When he managed to find the book’s title at the top of the page, his face fell.

Erm, this book Sir? It’s called… ‘An Introduction to Georgian Poetry’.

Splendid! said Mr McGuinness. So I am certain that you can give me the names of three prominent Georgian poets? I certainly hope you can, else the entire table will be joining me on Friday evening.

Friday detention was no laughing matter. Errant pupils were required to stay behind long after classes ended, often to help out with odd jobs around the school.

To our astonishment however, Tony immediately came up with three names: Alexander Chivadze, David Kipiani and Ramaz Shengalia. This time it was Mr McGuinness whose face dropped.

Hmmm. Very good, he said after a long silence. Carry on chaps, just a bit less noise please. He walked back to his desk.

Fortunately, as Tony well knew, McGuinness was a rugby man. He knew nothing about football. He also clearly knew nothing about Georgian poetry. Had he done so, he might have been aware of the fact that Alexander Chivadze, David Kipiani and Ramaz Shengalia were not Georgian poets. They were all Georgian footballers who had played for the Soviet national team.

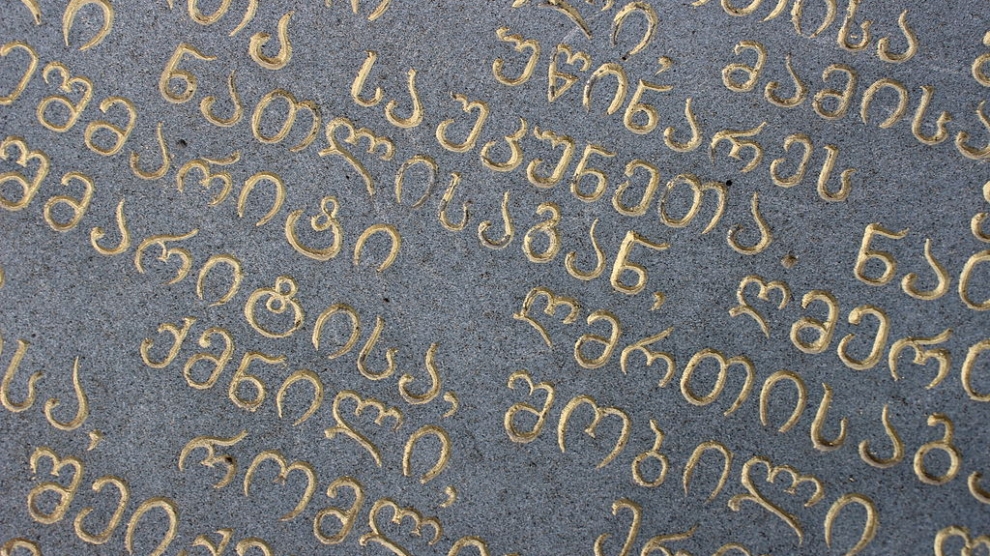

More fortunately, Tony (and those of us who didn’t want to carry out DIY around our school) had been lucky that he had not opened the Georgian poetry book just a few pages further on. For there were written some of the most famous Georgian poems, all in the impenetrable Georgian script.

At first glance, the Georgian alphabet is at once both quite beautiful and utterly (to the uninitiated) incomprehensible. For those of us brought up with Latin alphabets there is very little to work with. Both Greek and Cyrillic do at least have a few common roots that we can grasp on to help with comprehension. Georgian has none.

Not so long ago, for the visitor to Georgia this could be a problem. On my first visit to the country many years ago, finding my way around the capital Tbilisi was not easy. Beyond the city’s main street, named after Shota Rustaveli (who, as Tony Duggan would know had he actually read An Introduction to Georgian Poetry, is the country’s most famous poet) very few street signs were transliterated into the Latin script. Almost all streets signs were in Georgian only.

Returning to Georgia last week, to the country’s second largest city, Batumi, on the Black Sea coast, I was pleasantly surprised to discover that things have changed. Street names are now written in both Georgian and Latin, as are town and village names on highways. It is a simple and yet clear demonstration of how much the country has opened up to the rest of the world in recent years. Not knowing the Georgian alphabet is no longer an obstacle to visiting the country.

Georgians – quite rightly, however – remain extremely proud of their alphabet. So much so that since 2011 a 130-metre tower has dominated the seafront at Batumi as a testament to the uniqueness of the Georgian alphabet and people. The structure, known as the Alphabet Tower, combines the design of DNA, in its familiar double helix pattern, with two bands rising up the tower each holding the 33 letters of the modern Georgian alphabet. The letters are each four metres tall.

I have therefore set myself the task of learning this most attractive of scripts. Quite besotted with Georgia after a week of amazing wine, sensational food and gregarious locals, I have decided to visit again the first chance I get. This will almost certainly be next winter, when I plan on visiting one of Georgia’s fabulous ski resorts. I have vowed that by then I would have mastered the alphabet: indeed, I began my studies on the plane on the way home.

Who knows? I may also by then be able to recite some of Rustaveli’s verse. Tony Duggan and Mr McGuinness would no doubt approve.

—

Top photo: Rocketfall/Flickr/CC BY-SA 2.0).