The Covid-19 pandemic threatens hard-won gains in health and education over the past decade, especially in the poorest countries, a new World Bank Group analysis finds. Investments in human capital — the knowledge, skills, and health that people accumulate over their lives — are key to unlocking a child’s potential and to improving economic growth in every country.

The World Bank Group’s 2020 Human Capital Index includes health and education data for 174 countries – covering 98 per cent of the world’s population – up to March 2020, providing a pre-pandemic baseline on the health and education of children. The analysis shows that pre-pandemic, most countries had made steady progress in building human capital of children, with the biggest strides made in low-income countries. Despite this progress, and even before the effects of the pandemic, a child born in a typical country could expect to achieve just 56 per cent of their potential human capital, relative to a benchmark of complete education and full health.

“The pandemic puts at risk the decade’s progress in building human capital, including the improvements in health, survival rates, school enrollment, and reduced stunting. The economic impact of the pandemic has been particularly deep for women and for the most disadvantaged families, leaving many vulnerable to food insecurity and poverty,” says World Bank Group President David Malpass. “Protecting and investing in people is vital as countries work to lay the foundation for sustainable, inclusive recoveries and future growth.”

Due to the pandemic’s impact, most children – more than one billion – have been out of school and could lose out, on average, half a year of schooling, adjusted for learning, translating into considerable monetary losses. Data also shows significant disruptions to essential health services for women and children, with many children missing out on crucial vaccinations.

The index measures the human capital that a child born today can expect to attain by their 18th birthday, given the risks of poor health and poor education prevailing in their country. The index incorporates measures of different dimensions of human capital: health (child survival, stunting and adult survival rates) and the quantity and quality of schooling (expected years of schooling and international test scores).

Human capital has intrinsic value that is undeniably important, but difficult to quantify. This in turn makes it challenging to combine its different components into a single measure. The index uses global estimates of the economic returns to education and health to create an integrated index that captures the expected productivity of a child born today as a future worker, relative to a benchmark – the same for all countries – of complete education and full health.

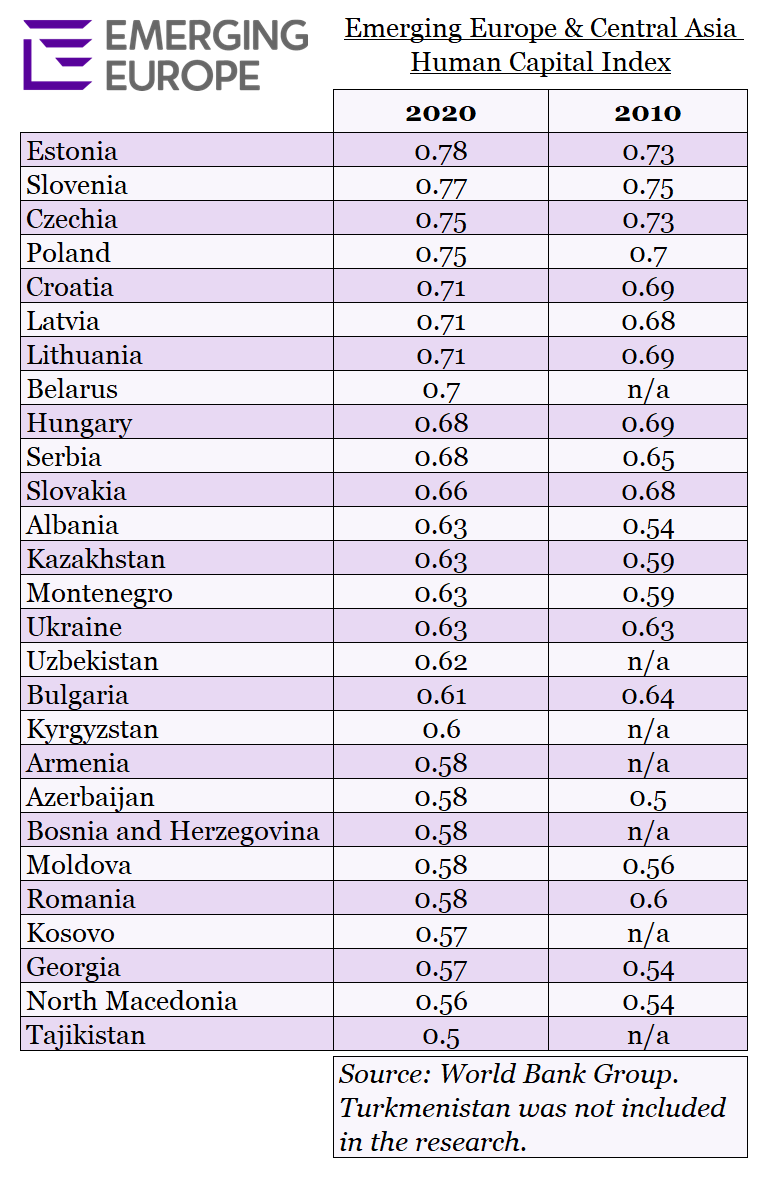

In emerging Europe, Estonia can boast the region’s highest Human Capital Index score, of 0.78. Of all the 27 countries in emerging Europe Europe and Central Asia included in the 2020 report, almost all are in the top half, and its findings are broadly in line with the relatively high incomes of countries in the region, with richer countries able to invest more in basic education and health services than poorer countries. However, there are significant variations within the region. Among the region’s emerging and developing economies, while a child born in Estonia can expect to achieve 78 per cent of the productivity of a fully-educated adult in optimal health, a child born in Tajikistan can expect to achieve only 50 per cent.

“Governments in Europe and Central Asia have done well in prioritising investment in health and education, which are key drivers of growth and development. The challenges unleashed by Covid-19, however, require an even stronger policy response, including greater use of technology to improve service delivery and enhanced social assistance programs, to ensure that people receive quality education and health care,” says Anna Bjerde, World Bank vice president for the Europe and Central Asia region.

Overall, health outcomes in the region are relatively good by global standards. Over the last 10 years, child mortality rates have dropped considerably, with Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan posting the largest improvements in child mortality. Similarly, child stunting rates have also dropped considerably, most notably in Albania, Azerbaijan and North Macedonia.

Adult mortality rates have also declined significantly, with Kazakhstan and Ukraine posting the best improvements. However, adult mortality rates remain high in several countries.

The region’s basic education outcomes offer a mixed picture, although the region performs well by global standards. Over the past decade, expected years of schooling have increased, with Azerbaijan, Albania, Montenegro and Poland making the largest gains – mainly due to improvements in secondary school and pre-primary enrollments. However, expected years of schooling also declined in a number of countries, including Bulgaria, Moldova, Romania and Ukraine.

Education quality, on average, has however not improved across the region in the past decade. Countries that have seen declines in education quality include Bulgaria and Ukraine. Countries that made improvements in education quality include Albania, Moldova, and Montenegro.

One of the most disappointing scores in the region is that of Romania: at 0.58, it is lower than the 0.6 scored a decade ago. The country now scores lower than the average for the Europe and Central Asia region, and the same as its far poorer neighbour, Moldova, whose own trajectory is upwards.

Today, a child in Romania can expect to complete just 11.8 years of pre-primary, primary and secondary school by age 18, compared with 12.6 years in 2010. When years of schooling are adjusted for the quality of learning, the World Bank estimates that a child in Romania only benefits from 8.4 years of schooling, a learning gap of 3.4 years. In terms of health, the percentage of 15-year-olds that will survive to age 60 stands at only 88 per cent, compared to 93 per cent in France and 95 per cent in Sweden.

“Once again, the Human Capital Index draws attention to the fact that Romania needs to urgently invest in the health and education of its children,” says Tatiana Proskuryakova, World Bank country manager for Romania and Hungary.

Globally, the highest human capital score can be found in Singapore: 0.88. The lowest is in South Sudan, 0.31.

—

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.