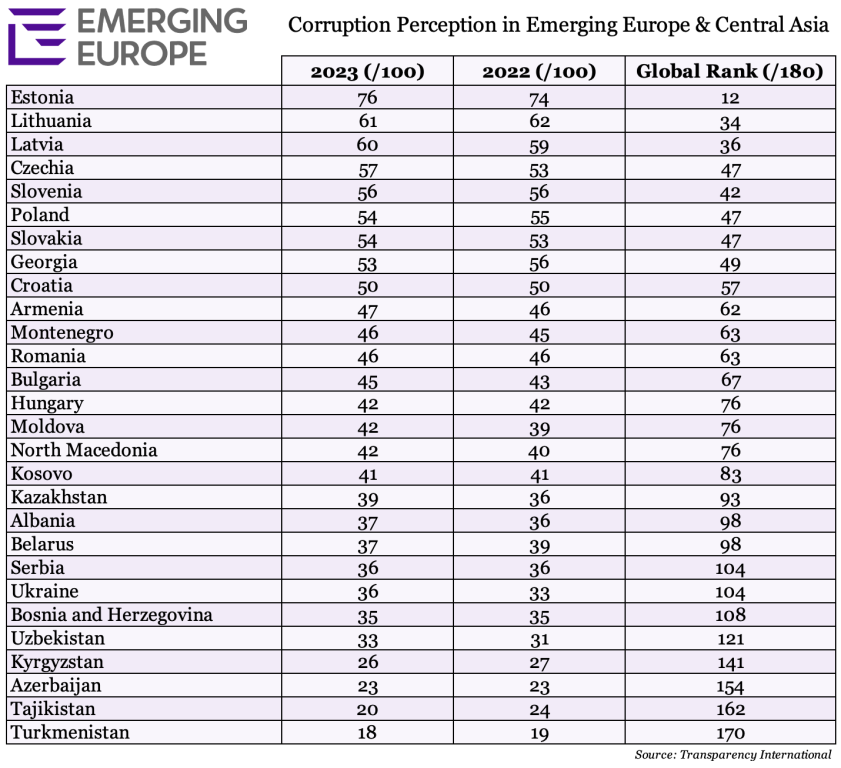

Low scores on the latest Corruption Perceptions Index in many countries across Eastern Europe and Central Asia reflect systemic governance deficits and a lack of independent oversight. Improvement in some countries of the region however offers a glimmer of hope.

The 2023 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), published this week by Transparency International, shows that Eastern Europe and Central Asia are grappling with dysfunctional rule of law, escalating authoritarianism, and pervasive corruption. (Transparency defines Eastern Europe and Central Asia as those countries of the region not currently members of the European Union).

Against a backdrop of widespread democratic regression and compromised justice systems, the result is a diminished grasp on controlling corruption.

Despite the strong challenges faced in much of the region, change is possible, as evidenced by progress in five countries which have significantly improved their CPI scores since 2014.

“Public institutions, including the police, prosecutors, and the courts, often face challenges in investigating and punishing those who abuse their power to steal public funds,” says Altynai Myrzabekova, regional advisor for Eastern Europe and Central Asia at Transparency International.

“In a region marked by war and increased poverty, it is crucial for leaders to prioritise actions that contribute to the common good. Substantial reforms in justice systems across the region are key to preventing corruption from thriving.”

The CPI ranks 180 countries and territories by their perceived levels of public sector corruption, according to experts and businesspeople.

Leading the group of improvers is Moldova, which continues to prioritise strengthening democracy, anti-corruption measures, and the rule of law. Central to its reforms is bolstering the independence and effectiveness of the judiciary, minimising political interference, and preventing the manipulation of legal procedures.

Its proximity to Russia’s war against Ukraine and historical ties with Russia create external pressures, occasionally impeding reform processes and elevating corruption risks.

Armenia, Kosovo, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan have also significantly improved their CPI scores over the past 10 years.

Deep systemic issues

Broadly, however, the picture for the region is bleak. The Eastern Europe and Central Asia average score of 35 (out of 100) makes it the second lowest scoring region in the world, and only one country (Georgia) scores above 50.

Even here, however, corruption remains a problem, indicating a deeper systemic issue—the concentration of power and the pervasive influence of elites on state institutions and decision making.

For several years, Georgia has been experiencing democratic backsliding, where deepening state capture and high-level corruption are turning the government into a kleptocracy.

The recent “return” to active politics of Bidzina Ivanishvili, the founder of the ruling party, is another sign that he has been instrumental in the capture of the country’s institutions. Once celebrated as an anti-corruption champion, Georgia’s corruption problem has grown to the point that it is now one of several major obstacles to EU integration, Transparency warns.

Ranking at the bottom in the region, Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan continue to struggle with severe corruption issues. Authoritarian control over state institutions by ruling elites has firmly taken root, with corruption being used to sustain power and evade accountability.

The low scores of these countries reflect systemic governance deficits and a lack of independent oversight, where corruption erodes various levels of society and state, while undermining civic and political rights.

Problems too in the EU

There are also issues with some countries of the emerging Europe region that are European Union members. Poland’s seven-point decline over the last decade showcases systematic efforts by the previous ruling Law and Order (PiS) party to monopolise power at the expense of public interest, while in Slovakia, previous progress in the prosecution of corruption has been tainted by the country’s new government’s controversial dismissals in the justice sector.

This was swiftly followed by legislative measures aimed at closing the special prosecutor’s office responsible for combating corruption and reducing criminal sanctions for corruption. If adopted, these changes would significantly undermine the rule of law and democratic stability, fostering an environment of impunity for corruption.

In Hungary, over a decade of systemic breach of the rule of law has created a system where high-level corruption thrives unsanctioned, Transparency claims. The unconvincing implementation of rule of law reforms, coupled with a recent legislative initiative to silence remaining critics, reveal the government’s commitment to protect the status quo.

Despite the adoption of long-overdue legislation on whistleblowing, Bulgaria’s significant problems with the rule of law and oligarchic influence remain, despite the legislative reform agendas of consecutive governments. Long overdue legislation on whistleblowing has been adopted, but challenges with its implementation are evident.

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.

Add Comment