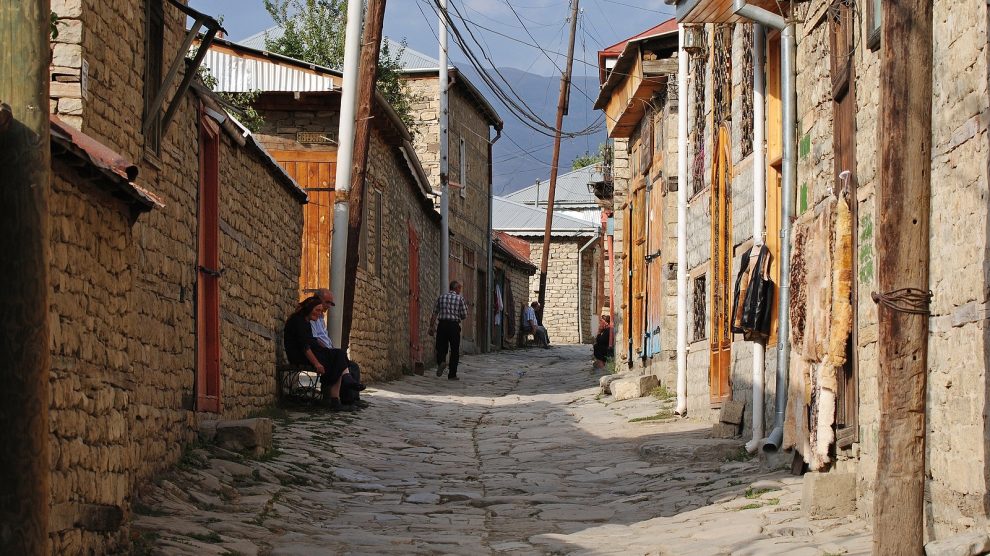

Azerbaijan’s economy and population are increasingly concentrated in the Greater Baku Area. As inequality remains the highest in the region and opportunities dwindle in rural areas, Azerbaijan must address the drivers of internal migration before the issue worsens into a crisis.

Since Azerbaijan gained independence in 1991, its state institutions and industry have concentrated into the Absheron peninsula’s Greater Baku Area, comprised of Baku, Sumqayit, and satellite cities.

Greater Baku’s location on the Caspian Sea gives it proximity to the offshore oil and gas reserves that produce 90 per cent of the country’s exports—and almost two-thirds of total budget revenue—and positions it as a hub for trans-Caspian trade between Europe, Central Asia, China, Russia, and Iran.

- Time is running out for Nagorno-Karabakh

- Development of the Trans-Caspian transport network will boost regional competitiveness

- Georgia’s mountains (and people) deserve better roads

As fossil fuel exports boomed, growth was sustained at 11 per cent from 2000 to 2015 and poverty declined from 49 per cent in 2004 to 4.9 per cent in 2014.

The benefits of this growth were not equitably or spatially distributed—a small elite in Greater Baku prospered the most. According to a 2021 World Bank report, Azerbaijan exhibits more than two times the inequality of any other country in Europe and Central Asia.

Rural to urban migration

Incomes of the population outside of Greater Baku do not correspond proportionately to the level of economic activity or population density.

While over 40 per cent of the population works in agriculture, the sector accounts for only 5.7 per cent of gross domestic product due to undeveloped agro-processing industries, limited access to finance, poor market linkages, and lack of skills and knowledge on modern agricultural technologies.

The departure of educated and skilled workers from rural areas for Baku or other countries further worsens human capital gaps between urban and rural populations.

“If the active and dynamic part of the population from the regions flows to the capital, the development of the regions weakens significantly,” suggested economist Rovshan Aghayev for the Baku Research Institute. “That is because the depopulation of rural regions is not related to the production, migrants are also consumers, and as internal migration expands, regions lose their advantages as markets.”

Some 47 per cent of Azerbaijanis and over 60 per cent of Azerbaijan’s poor live in rural areas. Over a million Azerbaijanis have emigrated to Russia, Turkey, the European Union, Ukraine, Israel, Central Asia, and elsewhere. Of Azerbaijan’s 69 districts, 50 continue to register negative net migration, chiefly from rural residents moving to urban centres for work or education.

Displacement from the Karabakh conflict

While many of Azerbaijan’s urban residents were ethnic Russians and Armenians during the Soviet era, many Russians emigrated amid the collapse of the Soviet Union and tens of thousands of ethnic Armenians were expelled from Azerbaijan amid anti-Armenian pogroms and the First Karabakh War.

That war resulted in Armenian forces seizing Nagorno-Karabakh and surrounding territory—recognised under international law as Azerbaijan—and establishing the breakaway separatist state of the Republic of Artsakh.

Before the war, Azerbaijanis were the largest minority in Armenia, but now, virtually none remain. Various sources estimate between 613,000 and 789,000 ethnic Azerbaijanis are internally displaced persons from the Karabakh conflict and between 160,000 and 200,000 are refugees from Armenia-proper. The government of Azerbaijan says it has a total of 1.2 million refugees and internally displaced people within its borders, including from the Karabakh conflict, natural disasters, and other causes.

With an official population of 10 million, these displaced persons make up a huge segment of Azerbaijan. While the government closed the sprawling IDP tent cities in 2007, at least 400,000 remained in substandard housing as of 2012. Today, many live in large informal settlements on the outskirts of cities and commute to areas with more economic activity for work. Some commute from the far eastern and northern borders of the country to drilling rigs in the Caspian Sea for weeks at a time.

Targeted social assistance programmes reach less than 10 percent of the population, and Azerbaijanis from areas with high levels of informality are proportionately under-represented in pension programmes.

A path forward

The World Bank has identified expanding access to high-speed mobile broadband connectivity as an important way to expand economic opportunities.

Azerbaijan ranks 111th of 175 countries with an average fixed broadband speed of 23.5 Mbps, and there is a 20-percentage point gap between rural and urban households in fixed internet penetration.

The World Bank attributes this digital divide to shortages of fixed infrastructure and lower levels of digital literacy in rural areas.

However, mobile phones are already widely used in rural areas, which presents a solid foundation for digital connectivity. If Azerbaijan can make broadband internet faster, cheaper, and more accessible, it could offer a lifeline to rural communities that otherwise face pressure to move to cities or to emigrate.

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.

Add Comment