In 2019, Romania celebrated 152 years since it first circulated its own currency and more than 100 years from the unification of the three historical Romanian provinces. Romania issued its first proper and freely convertible currency in gold (the leu) in May 1867. The National Bank of Romania (BNR) was established in 1880 and the first proper banknotes printed by Romania’s central bank are dated 19 January 1881. In modern times and to the surprise of the international community, the Romanian authorities decided to join the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, international financial institutions established at Bretton Woods on July 22, 1944 (75 years ago). The IMF Charter was signed by Romania on December 15, 1972. This was a bold achievement, especially more so that Romania was only the second socialist country to join the IMF (after Yugoslavia – a founding member). Romania’s membership in such prestigious international financial institutions offered the leu strong financial support in enforcing its status as a trustworthy currency. Other socialist countries followed Romania. However, during the last years of socialist development, macro-economic disequilibria started to appear and gain significance. This led to the well-known December 1989 events. The leu’s exchange rate, artificially kept at the level of 15 lei/US dollar, had a negative impact on the whole economy.

Soon after the events of December 1989, the new Romanian authorities introduced very bold measures regarding its currency. First of all, the very restrictive foreign exchange regime was relaxed during the last days of 1989. The restrictions regarding the holding of foreign currencies were also abolished in December 1989. Also, on February 1, 1990, the commercial and non-commercial exchange rates were unified at 21 lei/US dollar (from 8.74 lei/US dollar for the non-commercial exchange rate and 14.23 Lei/US dollar for the commercial, as recorded as of end-January 1990). Nevertheless, the level of 21 lei/US dollar was not the leu’s equilibrium exchange rate. It was an important step, but not a sufficient one. As of November 1, 1990, a new depreciation of the leu took place, at a higher level, of 35 lei/US dollar. A very bold depreciation of the currency to 60 lei/US dollar was soon the eventual result. The leu’s exchange rate was quoted on a daily basis since then and the level of 200 lei/US dollar was reached thereafter. Those dramatic days of the leu were the clear reflection of the sharp economic decline registered then by the economy and starting of building up of foreign debt.

Under the circumstances, the leu started to have parallel exchange rates again. Repeated attempts to unify the “grey” market exchange rates with the one quoted in the interbank market were made in 1991 and the following years. The leu’s exchange rate was frequently “frozen” or, in more precise terms, it was “manipulated”. The run after US dollars had already started. The “dollarisation” of the economy became a common and almost continuous feature. A difficult period for the leu’s destiny. The following years were also very difficult for the leu. Large depreciations followed (295 per cent in 1993). The paradox consisted in the fact that, while the leu depreciated more than double in nominal terms, the gap versus the quotations made by the “foreign exchange houses” and by the “black market” or by the “grey market” (at 1,700 – 1,800 Lei/US dollar) continued to increase. In August 1994, the NBR authorised the commercial banks to publish their own quotations for the leu. The official rate was supposed to be a mere average of those quotations. “Freedom” remained in place until 1996 when the BNR interfered again. The dealer licences of most commercial banks were withdrawn (in March 1996 only four banks were allowed to quote the leu). Large gaps started to appear between the quoted exchange rate and the rates from exchange bureaus (up to 25 per cent in November 1996). Such actions diminished the trust of the international markets in the leu.

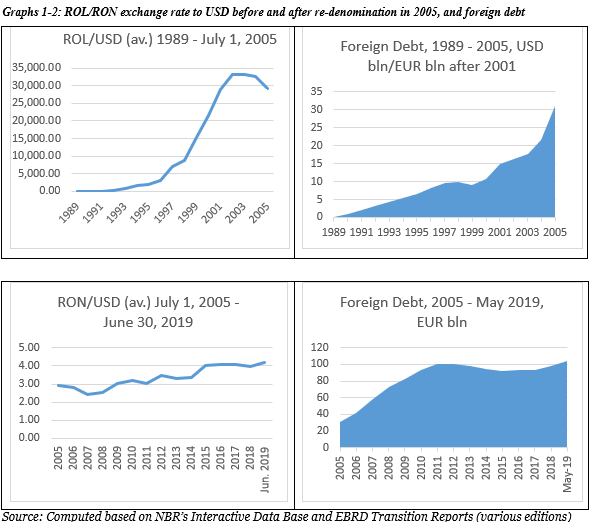

The levels of the leu’s exchange rate reached in the first years of the 21st century (20,000-30,000 lei/US dollar and over 36,000 lei/euro) were not sustainable from many points of view. The cash in circulation was very difficult to handle and, more importantly, the trust of the population in a weaker and weaker leu (printed in banknotes with larger and larger denominations – up to one million lei) was running out. Under such circumstances, on July 1, 2005, the BNR took the right decision to re-denominate the old Romanian leu (ROL) and to print a new currency, the new Romanian leu (RON), in what was called a new monetary reform (10,000 old Romanian lei were changed for one new Romanian leu). Also, the re-denomination was presented as a step in the right direction in view of Romania’s declared goal to adopt the euro (a goalpost moved many times). But by the end of 2005, the external debt had already accumulated to 30.9 billion euros.

The correlation between the foreign debt of Romania (increasing) and the leu’s exchange rate (devaluating) is obvious from the two graphs below. While the mathematical direct correlation will imply the utilisation of a linear function with many variables (current account, exchange rates for key foreign currencies, foreign debt service, flow of remittances, psychological factors, interest rates for external loans, etc.), the trends above clearly demonstrate that in the longer term an indebted country needs to depreciate its currency to stimulate exports and services and to reduce its imports. There are many factors at play in such a model, but the conclusion is presented below.

In the 14 years since the re-denomination, the leu has continued to fluctuate and to follow what could easily be called a tumultuous evolution of the Romanian economy and a worrisome accumulation of foreign debt. On top of this, the severe international banking crisis of October 2008 left a heavy mark on the leu’s exchange rate. Also, like many other countries in transition, Romania has suffered enormously and continues to suffer from the plague of corruption. At the same time, Romania started to register large macro-economic disequilibria such as large trade and current account deficits, budgetary deficits (some of them large and persistent in certain periods of time), insufficient absorption of the EU funds during the last 10 years and major setbacks in fighting inflation (or hyper-inflation).

Meanwhile, Romania has also lost an important advantage, namely its nil level of external indebtedness when the regime was changed in December 1989. Romanian foreign debt reached a bewildering level of 103.5 billion euros as of end-May, especially if compared to its economic and commercial potential and despite significant remittances from abroad. The large transfers considerably helped the leu to stay afloat, but the trends are downwards. Pressure will continue as Romania has increased its foreign debt during 2019 by 4.1 billion euros and foreign currency reserves (not including gold) decreased to 31.4 billion euros as of end-June 2019. Both developments will be very challenging to handle and to keep under control. The social negative impact could not be greater and the former Yugoslavia’s and modern Greece’s lessons could not be more relevant for Romania in the current turbulent market conditions. “The ghost” of the persistent Greek foreign debt (at 218.7 per cent of its end-2018 GDP) is haunting the Balkans.

The leu’s exchange rate has followed a long and, sometimes, difficult and convoluted path during its 152 years of existence and more so after 1989. Its dramatic evolution from lei 5/US dollar at the unification of the country in 1919, up to lei 15/US dollars under the socialist regime to lei 29,695/US dollars at re-denomination in July 2005 and further to lei 4.25/US dollars (lei 4.73/euro) at the end of July 2019 says it all. After all, the leu’s exchange rate has been a mere reflection of the economy, domestic monetary and fiscal policies, international context and, during transition, increasing foreign debt. A well-known past lesson learned is valid more than ever: a currency is strong(er) as long as it is supported by a healthy and robust economy. Building such an economy should be a national goal for all Romanians. Moreover, the evolution of Romania’s external debt had also a direct impact of the fate of the leu. At the current high (and increasing) level, it could well be a concerning factor for leu’s exchange rate evolution in the future. Foreign debt should be firmly controlled and kept at a sustainable level. Otherwise, the consequences could be dramatic for generations to come.