From start-ups using animation to teach young people new languages to one of the world’s biggest anime brands, Moldova is home to an increasingly dynamic animation sector.

This is not how you would imagine Moldova’s capital. We are standing on a rooftop in the middle of Chișinău, and the wind plays with our hair. Below us are the offices of Crunchyroll, the ultimate brand for all things anime with roots in the US, which chose Moldova as one of its 16 offices around the globe. Its Chișinău operation is Crunchyroll’s second largest outside of the US, and one of the most fun places in the country to work.

“Animation will make Moldova better,” says Igor Canonic, Crunchyroll’s art director. “It’s really fun!”

It does feel like a lot of fun here. In Canonic’s view, animation tests your limits, teaches you how to solve problems and keeps young people off the streets.

Igor Canonic, Crunchyroll’s art director

So is Moldova the next promised land for moving pictures? It’s ironic, given that Moldova didn’t even have any animation programmes two years ago. That clearly wasn’t an obstacle.

“In Moldova, people do a lot of stuff by themselves,” Canonic explains. “They learn everything on YouTube.” That’s how Canonic himself studied animation. “I didn’t have any other choice,” he explains, spreading his hands. In his view, there aren’t many opportunities in Moldova to be creative. “Animation is one way for Moldovans to express themselves.”

Changing how we learn

At Tekwill, near Chișinău’s Technological University on the city’s outskirts, another group of animation lovers is working on a web application. Langly teaches English using Oxford methodology so that what you learn on the app can be integrated into the education system. Students can assess whether they have A1 or C3 levels.

The application’s cornerstone is animation. To keep around 90,000 users engaged, “we want to differ, to make it memorable,” Langly’s co-founder Natalia Sleptov says.

She proudly explains how an actual artist—and not AI—create their characters. “We make it with soul,” she says with a broad smile.

How do they make this heartfelt animation? They, too, use Google and YouTube to learn.

In Sleptov’s view, animation is on the up in Moldova. The war next door has boosted the sector even further as Ukrainian specialists crossed the border, seeking refuge and bringing their know-how.

Langly uses animation to make learning languages more fun

The new wave is on its way

“I would call it a new rise of the animation industry,” says Lev Voloshin, one of the leading forces behind Moldova’s new wave of animation. He explains that during the Soviet occupation, Moldovans would study animation in Moscow and return with their knowledge. The industry was thriving.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union the sector held on, running purely on enthusiasm, until smaller animation studios opened. These studios ran their own in-house training.

During his studies at the Academy of Art, Lovoshin spent his mornings studying and evenings working at Simpals, an animation studio. He learned everything about traditional animation from his Turkmen mentor, Serdar Djumaev.

In-house animation training can be inefficient, however. It takes a lot of time and effort. In 2021, with the support of the Ministry of Education, the United States International Development Agency (USAID) founded a Future Professions project to support university programmes in animation, the gaming industry, and multimedia.

‘Crazy, scary’

Voloshin was invited to create the study programmes and be part of creating Moldova’s first animation faculties for three universities: the Technical University of Moldova, Ion Creanga Pedagogical University, and Moldova’s Academy of Music, Theater, and Fine Arts.

“It was a crazy, scary, and hard time,” he remembers. Each programme differs: Ion Creanga’s programme is more for those interested in advertisements or teaching animation, while the Technical University emphasizes animated movies and the game industry more.

Animation director and teacher Lev Voloshin is hopeful about Moldovan animation

In his view, the hardest part of teaching is not technical. The programmes and tools are constantly changing; anyone can learn them online. The real challenge is storytelling and understanding the, “physics of the drama,” as Lev calls it. “We have the passion for animation but not enough people,” Voloshin says. “That’s why we need to focus on creativity and storytelling.” Moldova couldn’t compete with the vast number of specialists coming up in Asia.

I joined Voloshin during one session with three second-year animation students. Sitting around the table in a modern grey room at a creative media technology hub, Mediacor, the students show Voloshin what they’ve created. Some were nervously twitching their fingers.

“This year was quite hard and nerve-wracking,” Valeria, one of Moldova’s first animation students, says. “But we have a great group of students.”

They tell me their professors learned animation by themselves or studied abroad. Ana was ready to move abroad, too, but she heard about the new animation faculty at the Technical University of Moldova. She stayed but is worried about the competition in the animation field once she graduates.

Here come the awards

The first awards are coming in already. In May this year, Moldovan director Oleg Condrea won the Cannes 7th Art Awards for the best script for a dramatic short film, Tangled Tails, about a wise dog who faces serious problems.

“In Moldova, animation is more accessible than making movies,” Condrea tells me. “No need for actors or studios, high mountaintops, or the ocean. A great idea is enough. And if you make it in English, it can become an international movie.

“People who make [live action] movies in Moldova have difficulty going international, especially if it’s very specific and cultural. With animation, anyone can empathise with a character no matter where they live.”

“It opens the stage for the market and a bigger arena for the audience,” Condrea adds. “You have more tools to connect with people.”

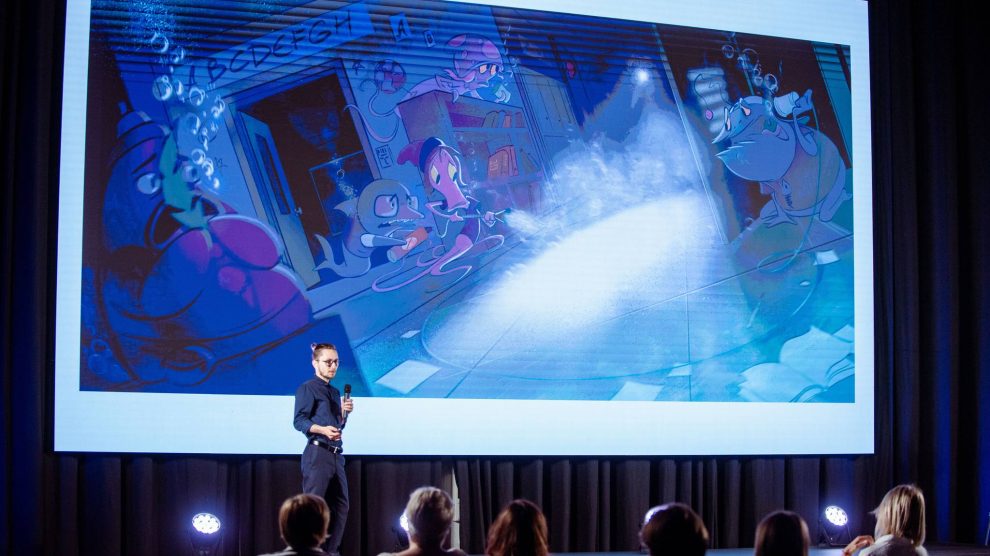

Award-winning director Oleg Condrea showcasing his work at Animest, an animation festival. Photo: Animest

Growing up in Moldova, with limited opportunities, young people had to find ways to get creative. Condrea was a skateboarder, but there were no skateparks in Moldova’s capital when he grew up. So he and his friends used to build obstacles or use stairs and anything they found in the city to do sports.

“So when I came into animation, I did the same: just used what I could,” he says. He was learning on his own and from mentors.

Hard, or easy?

Condrea says that animation is either “really hard” or “really easy”.

“Anyone with a vision can express themselves. It’s not all craftsmanship. Sometimes it’s just the visual. Or the tempo of the movie that attracts you. Sometimes it’s the feeling. Animation is easy if you stay true to yourself and your voice. It could also be hard because you must believe that what you want to say is valuable. You constantly change and make your ideas better.

“And yet, you must pretend they are already good when you show them to the audience. If you can walk on those two extremes, you can find peace. If something feels hard, I ask myself if it’s natural to me. Forcing something upon yourself and wondering why you fail is part of the problem.”

Condrea says that the appeal of animation in Moldova is the opportunity it offers to create world and characters. “Do you want to travel the world, show what you’ve dreamed of, and put it on the screen?” Animation, he suggests, does that.

A teacher of animation for two years, Condrea says that in his classrooms he sees people who are, “much smarter than I was at their age”.

“It forces me to think better. Sometimes, I tell them about my achievements, and they tell me it’s a good starting point. That’s amazing! They will be the future of animation in Moldova or the world. They can answer questions about social dilemmas, morality, and the technical part of drawing,” Condrea says.

Everybody loves animation

In animation, Condrea suggests, you have to be creative; your idea has to be worth it.

“I cannot invent a character that sits on a chair for 20 minutes. I struggle to make scenes dramatic sometimes. How do you make a scene with someone sitting on a chair dramatic? In animation, a composition or a physical movement does more than a facial expression.

“Sometimes, it’s just how you move the camera or the light. But it’s rewarding. It’s like knowing many different languages at once. But the bottom line is, if you have already caught the audience’s attention, you have to say something valuable.”

Lev Voloshin believes that if his country’s passion for animation can be turned into great stories, then one day, Moldova could become, “the Moldovawood of animation.”

That’s his secret dream. Why? “Because everybody loves animation.”

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.