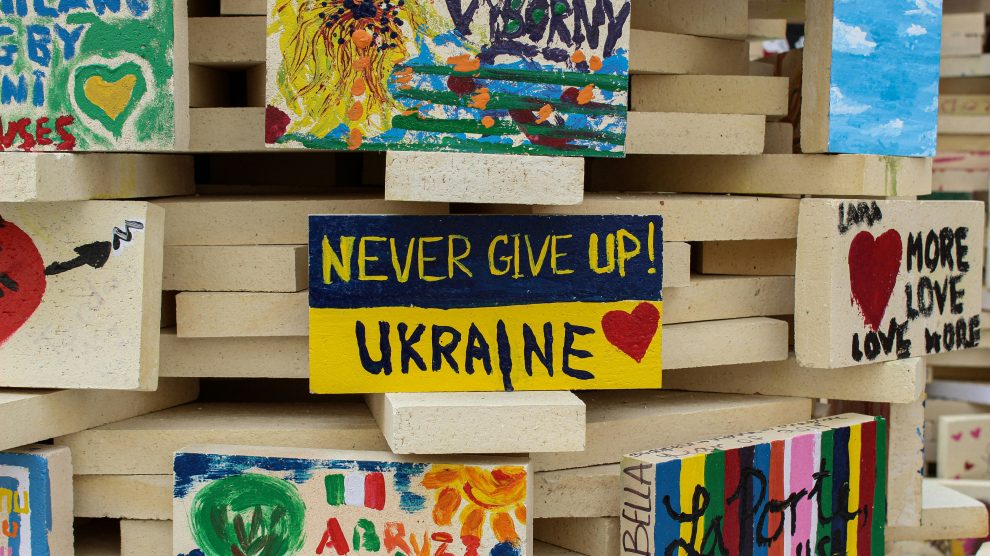

Catch up quickly with the stories from Central and Eastern Europe that matter, this week led by news of a poll that reveals weak levels of confidence in Ukraine’s chances of victory in its war against Russia.

Russia’s war on Ukraine

Europeans appear pessimistic about the outcome of Russia’s war on Ukraine, a major new poll revealed this week. An average of just 10 per cent of Europeans across 12 countries now believe that Ukraine will win. Twice as many expect a Russian victory.

This weak confidence in Ukraine’s chances of victory is visible all over Europe. Poland, Portugal, and Sweden are the most optimistic countries. But even there, only 17 per cent of respondents believe Ukraine will prevail—and in Sweden 19 per cent think Russia will win.

Everywhere except for Poland and Portugal more people expect a Russian victory than a Ukrainian one, and as many as 31 per cent in Hungary and 30 per cent in Greece expect this. But the prevailing response everywhere polled (37 per cent on average) is that the war will end in a settlement—with that response comfortably outweighing a Ukrainian victory even in Poland.

However, expecting a settlement is not the same as preferring such an outcome. When Europeans were asked what action they want their governments to take on Ukraine, a more varied picture emerges.

Respondents in three countries—Poland, Portugal, and Sweden—express a clear preference for supporting Ukraine to take back its territory. But in five others—Austria, Greece, Hungary, Italy, and Romania—people tend to want their governments to push Kyiv to accept a settlement.

Ukraine said on Tuesday that it’s planning an additional route via the Danube River to boost exports to pre-war levels as a spat with Poland over agricultural deliveries blocks a land border with the European Union.

The Danube became a priority avenue for Ukrainian supplies after Russia exited a United Nations-backed safe corridor in the Black Sea last year. Still, a significant amount of crops also flow by rail and road via the EU, and Polish farmers—protesting what they call an uncontrolled flood of Ukrainian food products—are blocking a key route.

“Our plans for this year is to remove all artificial obstacles for exporters and we are working to improve domestic logistics,” Ukrainian Infrastructure Minister Oleksandr Kubrakov said on the sidelines of the Munich Security Conference. “We are planning container transportation via the upper Danube” as Romania is “more predictable” than the Polish border.

The proposed new route—few details are immediately known—would run from the Ukrainian port of Izmail to the Romania’s Constanța and the Danube ports of Germany, according to the minister. The Ukrainian Danube Shipping Co. has already built a second large-tonnage SLG barge to deliver cargo, the Infrastructure Ministry said earlier this month.

The European Union agreed on Wednesday to slap Russia with a new round of sanctions, which for the first time target companies in mainland China suspected of helping the Kremlin get hold of forbidden items.

The sanctions have a heavy focus on fighting circumvention and go after firms around the world accused of providing Russia with advanced technology and military goods manufactured in the EU, particularly drone components.

Companies from Turkey and North Korea, among other countries, have also been targeted. Nearly 200 people and entities, mostly from Russia, have been added to the blacklist, which now contains more than 2,000 names.

The package, however, does not cover any person allegedly involved in the death of Alexei Navalny, the most prominent critic of President Vladimir Putin. Tighter restrictions on aluminium were not included either, as the topic remains divisive.

“We must keep degrading Putin’s war machine,” said Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission.

Other news from the region

Estonian Prime Minister Kaja Kallas on Sunday dismissed a warrant issued by Russia for her arrest, saying it was just an attempt to intimidate her amid speculation she could get a top European Union post. Estonia has been a supporter of Kyiv and Kallas has been one of Moscow’s most vocal critics since the Russian invasion of Ukraine nearly two years ago. Russian police placed her and several other Baltic politicians on a wanted list on February 13 for destroying Soviet-era monuments. “It’s Russia’s playbook. It’s nothing surprising and we are not afraid,” Kallas said.

Hungary levied a hefty fine on six opposition parties this week over allegations of illegal campaign financing, stripping them of crucial funding ahead of European Parliament and local government elections later this year. The State Audit Office fined the parties, which had joined forces in 2022 against Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s ruling Fidesz party, a combined sum of more than 520 million forint (1.4 million US dollars). While Orbán has relented on some key disputes with European Union and NATO partners, he has left no chance for the opposition to challenge his rule at home.

Senior figures from Poland’s previous government are to be questioned by lawmakers over the alleged use of spyware to target critics. An inquiry will examine claims the Law and Justice (PiS)-led administration used the powerful Pegasus software to monitor opponents’ phones. The PiS government—which lost power in October—has previously denied the accusations. PiS leader Jarosław Kaczyński is among those who could be questioned. Ex-prime minister Beata Szydło, former justice minister Zbigniew Ziobro and former interior minister Mariusz Kamiński are all also set to be called to testify.

Brussels meanwhile this week has signalled it could end a years-long sanctions procedure against Poland by the summer after Donald Tusk’s government presented its plan for restoring judicial independence. The plan, seen by the Financial Times, sets out several bills that Tusk’s coalition will seek to pass in order to reform the judiciary and reverse the overhauls undertaken by the previous Polish government. The rule of law dispute with Warsaw prompted the European Commission to freeze more than 100 billion euros of Poland’s EU funds.

Romania may need until the end of the decade to bring its budget deficit down to a target set by European Union rules as the government contends with public resistance to fiscal restraint in an election year. Finance Minister Marcel Boloș said on Monday that a regime of annual budget cuts amounting to 0.5 per cent of gross domestic product under the EU’s new fiscal rules presents a “very hard” challenge. The country likely needs the seven years allotted by the fiscal framework to narrow the gap to three per cent of GDP from five per cent forecast for this year—a slower pace than originally projected.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan on Monday told Azerbaijan’s visiting leader that he wanted Baku to avoid future border flare-ups with Armenia and to pursue a lasting peace. Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev arrived in Ankara—Baku’s most important military and diplomatic supporter on the global stage— after holding rare talks with Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan hosted by German Chancellor Olaf Scholz in Munich. The Munich meeting’s stakes were raised by a deadly clash last week along the Azerbaijan-Armenian border that Yerevan said killed four Armenian troops.

Belarus holds a parliamentary election on Sunday, but there will be very little choice on offer for voters. While Belarusians will, in theory, be able to vote for candidates from four parties, the Belaya Rus party (created in 2007 with the sole purpose of supporting Lukashenko) will again win a healthy majority. The three other parties contesting the election (the Communist party of Belarus, the Republican part of Labour and Social Justice, and the Liberal Democratic party) are all loyal to Lukashenko and should win a handful of seats between them.

Thousands of minority Serbs in Kosovo on Monday protested a ban of the use of the Serbian currency in areas where they live, an issue that has been the cause of the latest crisis in relations between Serbia and Kosovo. Tensions escalated after the government of Kosovo, a former Serbian province, banned banks and other financial institutions in the Serb-populated areas from using the dinar in local transactions, starting February 1, and imposed the euro. The dinar was widely used in ethnic Serbian-dominated areas, especially in Kosovo’s north, to pay pensions and salaries.

Albania’s parliament on Thursday approved a controversial deal signed with Italy to host two holding centres for migrants rescued in Italian waters. The deal, which required a simple majority approval, passed with the backing of 77 MPs of the 140-seat parliament, with the opposition boycotting the vote. “The migrant deal harms national security, territorial integrity and the public’s interest,” right-wing opposition leader Gazmend Bardhi told reporters. The agreement has been denounced by rights groups, resulting in a legal challenge taken up by Albania’s top court in Tirana.

Photo by Yurii Khomitskyi on Unsplash.

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.

Add Comment