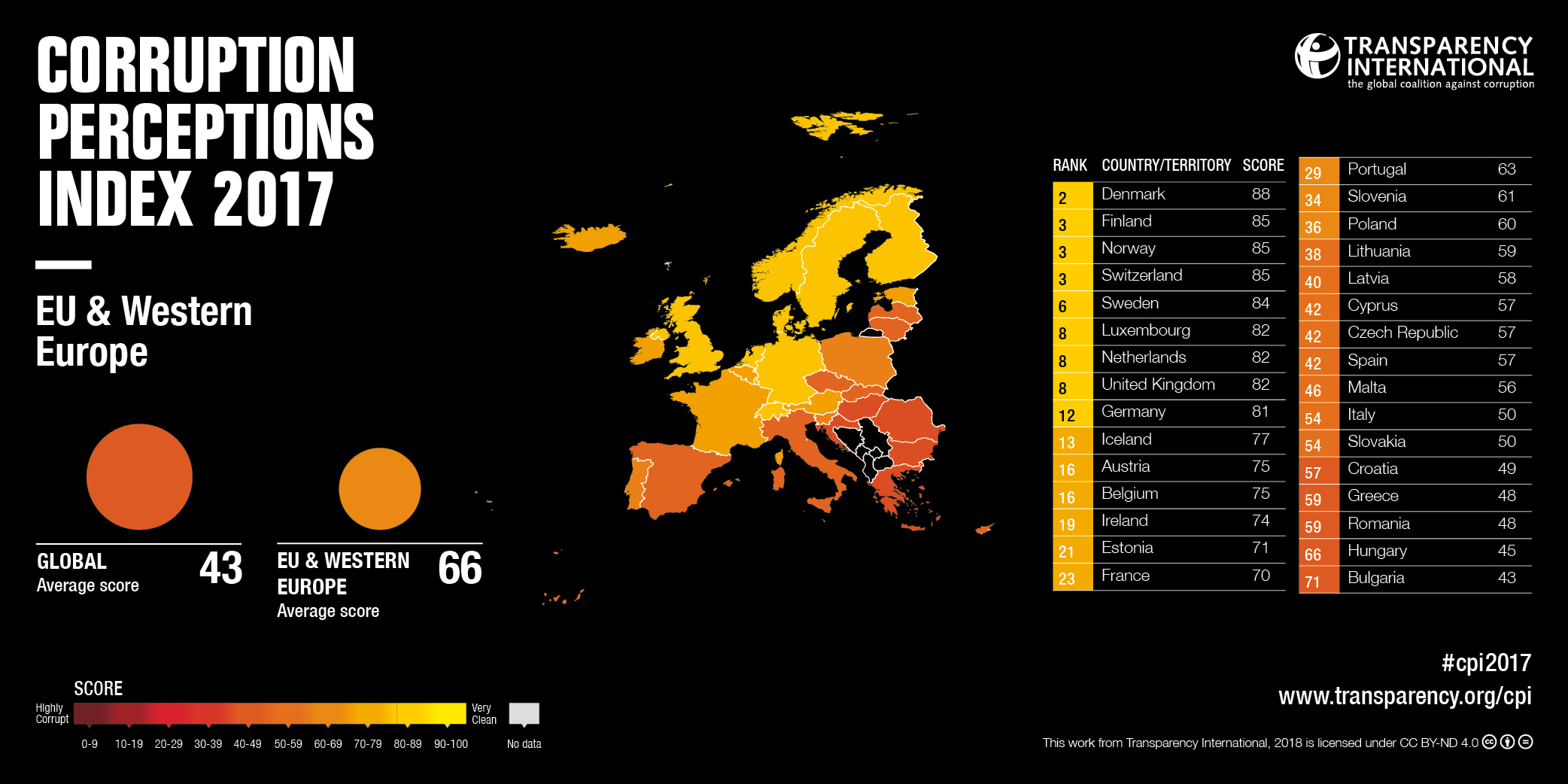

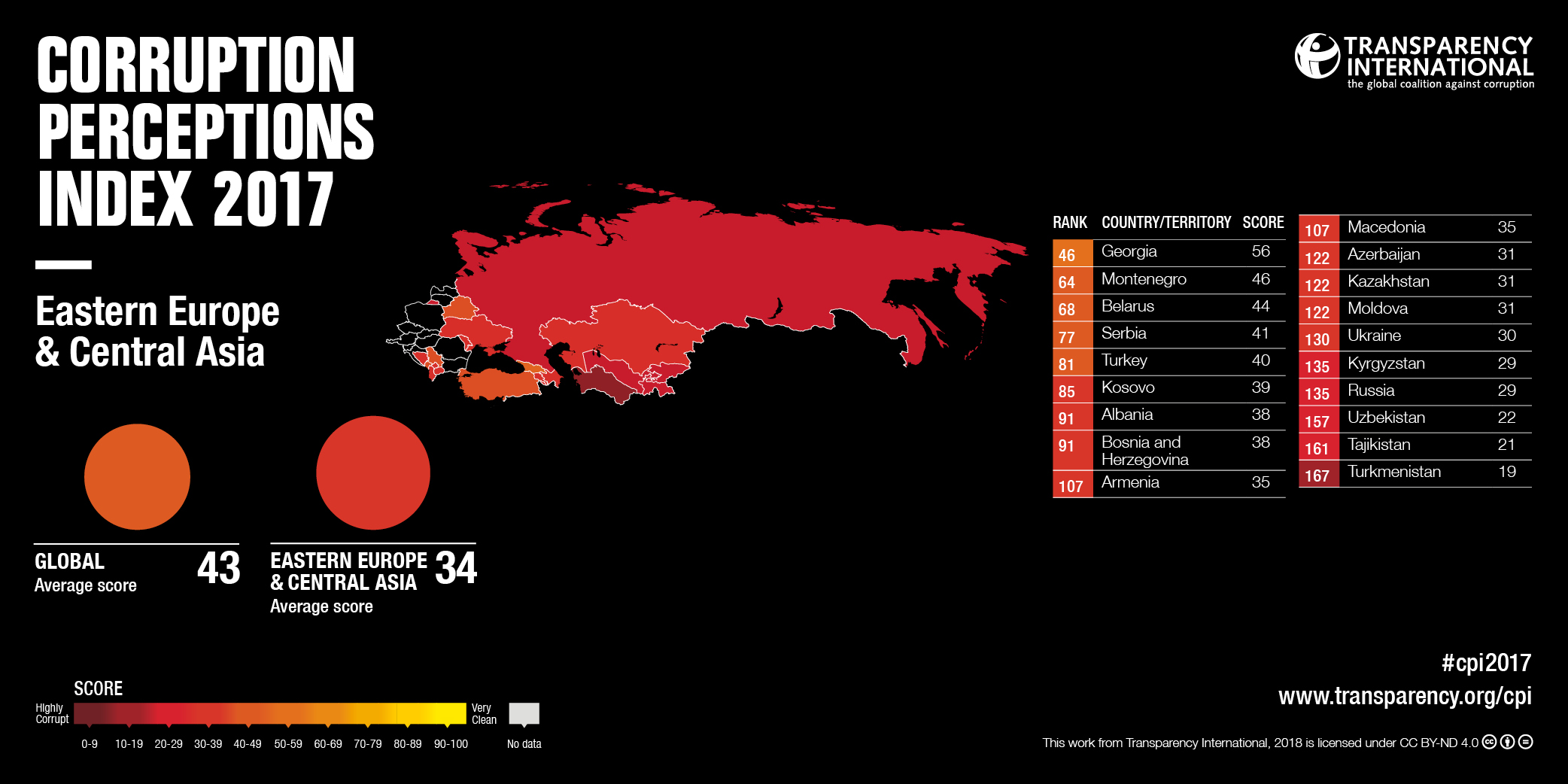

Estonia – by quite some distance – is viewed as being the least corrupt country in emerging Europe, according to the latest Corruption Perceptions Index, published at the end of February by Transparency International. The Baltic State ranks 21st globally, well ahead of the next emerging European nation, Slovenia, in 34th place. Ukraine is the lowest-ranked emerging European country, down in 130th place. The index ranks 180 countries and territories by their perceived levels of public sector corruption according to experts and business people.

One of the biggest concerns highlighted in the report is the way that non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are being targeted.

“In 2017, authoritarianism rose across eastern and south east Europe, hindering anti-corruption efforts and threatening civil liberties. Across the region, NGOs and independent media experienced challenges in their ability to monitor and criticise decision-makers,” reads the report. “For example, in Poland, government bodies took over the management and distribution of vital funds for non-government organisations. Similarly, in Romania, the government put forward a bill which imposes disproportionate reporting requirements on NGOs. Comparable laws directed at curbing NGOs also passed in countries throughout the region.”

Hungary was singled out for particularly fierce criticism.

“Hungary, which saw a ten-point decrease in the index over the last six years, moving from 55 in 2012 to 45 in 2017, is one of the most alarming examples of shrinking civil society space in eastern Europe. Recently, the country drafted legislation that threatens to restrict NGOs and revoke their charitable status. Equally troubling, the government also passed a law that stigmatises NGOs based on their funding structures and adds burdensome reporting requirements. As a result, more than 20 NGOs filed legal proceedings against the government in both the Hungarian Constitutional Court and European Court of Human Rights.”

Analysis of the results indicates that countries with the least protection for press and NGOs also tend to have the worst rates of corruption. Every week at least one journalist is killed in a country that is highly corrupt. The analysis, which incorporates data from the Committee to Protect Journalists, shows that in the last six years, more than nine out of 10 journalists were killed in countries that score 45 or less on the index.

“No activist or reporter should have to fear for their lives when speaking out against corruption,” said Patricia Moreira, managing director of Transparency International. “Given current crackdowns on both civil society and the media worldwide, we need to do more to protect those who speak up.”

Ukraine’s lowly position in the Index is down to “a lack of political will on the part of the country’s government for a resolute fight against corruption,” says Anastasiya Kozlovtseva, head of international relations at Transparency International Ukraine. “There is also a low level of trust for the Ukrainian courts, while regular legislative initiatives put forward by parliament which threaten the newly created anti-corruption infrastructure cannot be overlooked. As a result, corruption remains among the most acute problems faced by business and regular citizens.”

Globally, New Zealand remains the least corrupt country, while Somalia is the most corrupt.

Add Comment