After a few years of setbacks, European separatists are re-organized, re-energized, and marching across Europe’s fabric of nations. The far-right Sweden Democrats posted the biggest gains in Sweden’s September 9 election. Support for Germany’s far-right AfD party is at an all-time high. And separatists have steadily bumped up their election numbers in France, Denmark and Hungary.

The Balkans are another simmering hotspot of separatism that everyone should put on their radar.

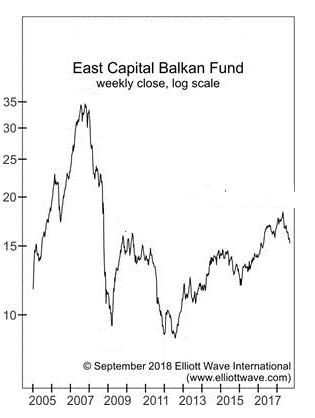

According to a recent Bloomberg article, Playing With Fire in Europe’s Powder Keg as Balkan Tensions Rise, “Europe is sleepwalking toward another rupture in the Balkans,” with world leaders from Russia, Turkey and the US jostling for power, and Balkan leaders “seeking to unpick ethnic and territorial agreements that have underpinned an anxious peace for two decades.” Unofficially backed by Moscow, Milorad Dodik, the leader of Republika Srpska, a Serb region of 1.2 million, has long-called for the secession of his region from Bosnia. Dodik has toned down that demand ahead of the upcoming Bosnian elections on October 7, but his movement should be getting a big boost from an increasingly negative social mood, which impels impulses to secede and separate. The dour mood is reflected in the region’s declining stock markets. Notice in our chart how the East Capital Balkan Fund, an actively managed fund which mainly invests in Romania, Croatia, Serbia, Turkey, Slovenia and Bulgaria, has struggled to retrace less than half of the decline from its 2007 peak. From an Elliott wave perspective, the impending and likely already-ongoing decline should see the winds of social mood squarely at the separatists’ backs.

The region’s loose patchwork of currency arrangements will only add to the financial chaos that secession movements thrive on. Slovenia, for example, is the region’s only official eurozone member, while Albania freely floats its currency in the foreign exchange markets. Macedonia, Bulgaria and Bosnia and Herzegovina peg their respective currencies to the euro, and even though Kosovo and Montenegro have unilaterally adopted the euro, neither country is represented in the European Central Bank or in the Eurogroup. These makeshift agreements will fall apart when the equity bear market returns, and regional economies begin to deteriorate.

Many experts assume that the euro will anchor these currencies and economies, but the euro itself is a relatively new experiment that will also struggle to survive the coming negative mood trend. From every vantage point, stability in the Balkans will soon be tested to an extent that hasn’t been seen in decades.

—

The views expressed in this opinion editorial are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Emerging Europe’s editorial policy.

Add Comment