Earlier this month, relations between Georgia and Russia hit a new low point following the protests in Tbilisi triggered by the visit to the city of a Russian communist MP, Sergey Gavrilov. For many people, seeing a Russian MP sitting in the chair normally occupied by the speaker of Georgia’s parliament was an unacceptable provocation, to which the Georgian government turned a blind eye. Gavrilov had to leave the country earlier than planned, and Moscow classified anti-Russian statements expressed during the protests as radical Russophobia, mostly to use is as pretext for declaring Georgia as a dangerous country for Russian visitors. Based on this claim, Vladimir Putin banned Russian airlines from flying to Georgia for an indefinite period.

Tensions kept mounting even before the decision entered into force. On July 6, Georgian opposition TV host Giorgi Gabunia attacked Putin with an extremely vulgar rant on his show. Although the Georgian government and civil society unanimously condemned the rant, the reaction from Russia was rather intimidating. The state Duma requested the government ban imports of Georgian wine and mineral water, as well as restrict money transfers between the countries (indeed, some Russian MPs went so far as to suggest that Georgia should extradite the journalist to Russia, where he should face charges). However, to the great surprise of many Russians and Georgians alike, Putin dismissed the initiative and did not support economic sanctions against Georgia out of “respect for the Georgian people.”

In spite of such a “considerate” move from Putin, the deterioration of relations between the two countries has triggered fierce debates about the stability of the Georgian economy, increasingly dependent on Russia and vulnerable to the effects of any prospective sanctions. With the memory of the last round of sanctions (2006-12) still fresh, it is crucial to understand the real extent to which the economy of Georgia is dependent on Russia and to explore the consequences that any new sanctions could have on the country.

The danger of Russia’s punitive trade policy

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia has been an important but unstable export market for Georgia. Although both parties signed a Free Trade Agreement in 1994, the Kremlin has been using access to its market as leverage to achieve political ends. Following a dramatic deterioration of relations between the two countries, Russia imposed an embargo on Georgian wine and mineral waters in 2006, greatly harming the country’s economy. As a result, the share of the Russian market in total exports decreased from 18 per cent in 2005 to two per cent in 2012. After the victory of the Georgian Dream coalition in 2012’s parliamentary elections, the two countries started the process of normalising relations, which led to the lifting of the embargo on Georgian products. This decision once again amplified Georgia’s economic dependence on the Russian market, and its share in total exports reached 14.5 per cent in 2018. It has to be mentioned that whereas Georgia’s overall exports increased by 46 per cent between 2013-18, exports to Russia increased by 835 per cent.

Many commentators in Georgia also argue that should the level of hostility between the two countries increase, Russia could ban the export of some commodities to Georgia. As such, Georgia should – in their opinion – reduce import volumes from Russia to avoid the danger of a big deficit on crucial products, such as wheat or oil and petroleum. In 2018, Russia accounted for 84 per cent of total wheat imports and 23 per cent of oil and petroleum. Another way that Russia could affect Georgia’s economy is by increasing prices on products imported from Russia to Georgia.

Indeed, in a very recent example of how dangerous Russia’s decisions can be for the Georgian economy, Russia’s Federal Service for the Oversight of Consumer Protection and Welfare last month banned the eight biggest wine companies from exporting Georgian wine to Russia. Luckily, the previous Russian embargo on Georgian wine was a wake-up call to diversify export markets and last year Georgia exported its wine to 53 countries. Nowadays, Georgia has a free trade agreement with the European Union and China, which indicates that new Russian sanctions should not be as painful as back in 2006. However, decreasing the volume of exports to Russia will be difficult. This is due to a number of deep-rooted factors such as geographical proximity, popularity and high demand for Georgian products in Russia, the absence of strict quality standards on exports to Russia (making it easier to export there than to the EU, for example), and long-established business ties between various stakeholders in both countries.

Flight ban and reduced inflow of Russian tourists

The ban on flights from Russia to Georgia – and on Georgian airlines flying to Russia – while ostensibly introduced due to security concerns was in fact a way of pressuring the Georgian economy by means of reducing tourist inflows. Data suggest that the number of visitors from Russia has been growing fast (much like the amount of money spent by them in the country). Indeed, out of 4.1 million people who visited Georgia in 2012, 10 per cent (410,000) were visitors from Russia. In 2018, these numbers increased to 8.6 million and 16 per cent (1.4 million) respectively. That same year, international visitors and tourists spent in the country 3.2 billion US dollars and Russian tourists alone contributed 1.7 per cent of Georgia’s GDP, spending on average 510 US dollars per person per visit.

Despite the flight ban, Russians can still visit Georgia, either travelling by car or flying through a third country. As statistics show, 70 per cent of Russian tourists arrive via land borders. The National Bank of Georgia predicts that in 2019 the flight ban will translate into a loss of between 200-300 million US dollars, with the Georgian economy ministry predicting a loss 700 million US dollars. However, as it is unclear how long the flight ban will remain in place, it is hard to anticipate its exact effect on Georgia’s economy.

Many commentators in Georgia argue that the Georgian National Tourism Administration focused on increasing flows of incoming tourists, and overlooked threats associated with a growing number of tourists from an unfriendly country like Russia. By putting more effort into bringing more tourists from other countries, Georgia could diminish the risks of its over-dependence on tourism from the Russian Federation. To that end, the state should stop spending money on tourism marketing in Russia and redirect finances to other markets.

The danger of banning money transfers

Russia is a country with the second-largest immigrant population in the world and is the preferred destination for migrants from many ex-Soviet republics. According to Georgia’s State Ministry for Diaspora Issues, in 2015 there were 800,000 Georgians – almost half of the entire Georgian diaspora – living in Russia.

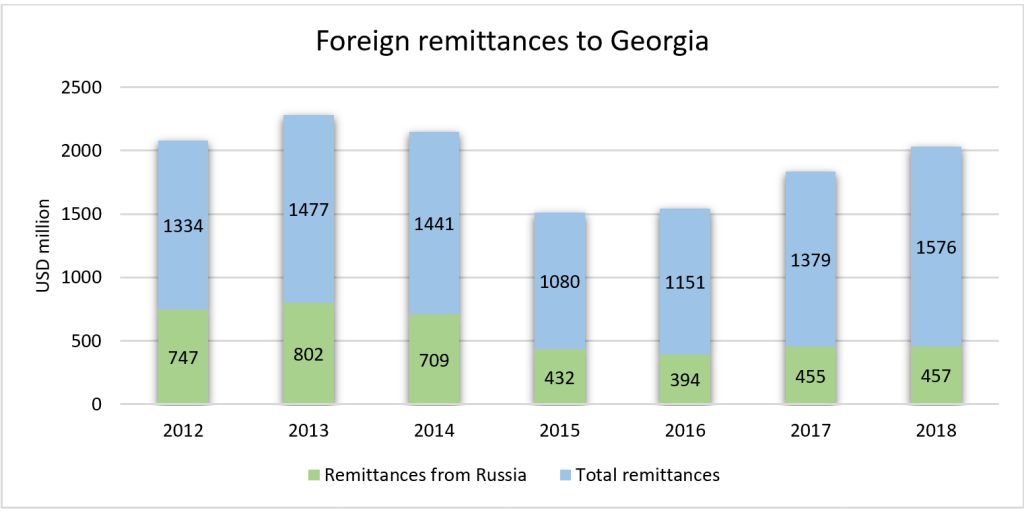

Money transfers (remittances), which the Georgian diaspora sends to their families and friends back at home are one of the main sources of foreign currency inflows into the country (after exports). According to the National Bank of Georgia, between 2012 and 2018 registered foreign remittances amounted to almost 10 billion US dollars, of which almost four billion US dollars was transferred from Russia. Needless to say, an economic crisis in the host country can also affect the economy in the remittances-recipient country, as demonstrated clearly by the drop in the volume of funds transferred to Georgia since 2014 when Russia’s economy began to stagnate.

Remittances can be viewed as strategically important for developing countries. Georgia’s economy is quite sensitive to foreign shocks, and money transfers from abroad perform the buffer function to withstand these shocks. Taking into consideration the significance of remittances received from Russia, the ban on money transfers can adversely affect household budgets in Georgia, possibly leading to a decrease in consumption. This in turn can adversely affect the economic growth and reduced inflow of foreign currency can trigger inflation. Nevertheless, a ban would be very efficient measure given that transfers can be made through third countries or online, beyond the control of the Russian state.

Russian foreign direct investment in Georgia

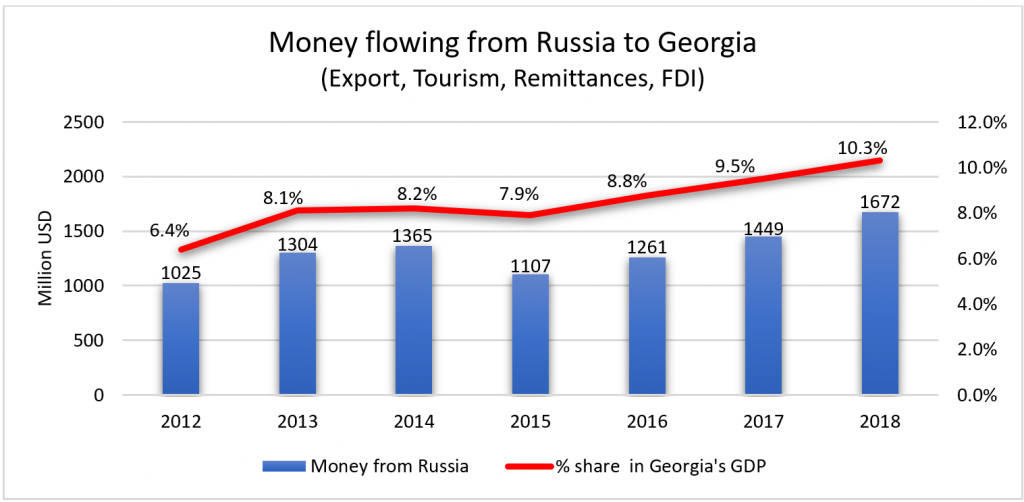

For countries with a small transitional economy like Georgia, special importance is attached to foreign direct investments (FDI). FDI significantly contributes to further development of the country, ensures the inflow of financial resources and new technology, helps the local workforce to enhance their skills and connects the state to international markets. Remarkably, whereas Russia is the top partner of Georgia in terms of export, tourism and remittances, it was only ninth on the list of biggest investors in Georgia in 2018. During 2012-18, FDI in Georgia amounted to 9.1 billion US dollars (lower than total remittances), and total FDI from Russia during this period was only 309 million US dollars, or approximately four per cent of total FDI. Therefore, it can be considered as the least effective leverage against Georgia.

Summary

The available evidence seems to suggest that new Russian sanctions pose a considerable danger to the Georgian economy as they target all channels through which Georgia receives over 95 per cent of money from Russia – exports, tourism, and remittances. In 2018, this totalled 10.3 per cent of Georgia’s GDP. However, these days, the country’s economy seems to be more resilient and better prepared for dealing with an economic embargo than in 2006. However, Georgia’s growing (since 2012) exports to and dependence on visitors from Russia mean that this can easily change. The Russian market is currently a low hanging fruit for Georgia and dependence will keep growing until Russia enforces sanctions again.

Interestingly enough, Russia has still managed to reap political dividends from the situation, with Putin getting brownie points for “saving” Georgians from the potentially devastating sanctions that his own parliament wanted to impose on the country. By doing that, he strengthened the already influential pro-Russian forces in Georgia, whose new rise in prominence is a major source of worry for those in the country who do not believe in the Kremlin’s good intentions. Whether by virtue of using hard power (the danger of sanctions) or soft power (gratitude for withholding the threat), Russia is highly unlikely to change its course towards its neighbour. Georgians should better prepare themselves – and their economy – for that.