The Romanian economy is currently enjoying a period of grace. According to the latest information provided by the country’s statistics office, GDP advanced in the first semester by 4.1 per cent, while at the end of August, the unemployment rate was 3.46 per cent compared with an average of 8.3 per cent in the euro area. It is important to note that 70 per cent of Romania’s unemployed reside in rural areas while one third of the total number is represented by people with no qualifications.

At first glance it seems like an ideal situation, but the reality is hiding tense relations on the labour market, with fewer than ever newcomers entering the market, and with diminishing skills. The percentage of Romanian young people (aged 20 to 34) in 2017 neither in employment nor in education was among the highest in EU, at 21.4 per cent compared to the EU average of 17.2 per cent.

Complaints are heard everyday regarding the quality of education, the level of GDP allocated to the sector and curricula considered outside the needs of the economy. What those needs look like is a question with an indefinite number of responses depending who is asked. The Romanian educational system has for the past 25 years seen continuous reform, the one tangible result being that Romania is ranked the last among EU countries in the PISA assessment, a test intended to measure the performance of 15-year-olds in mathematics, science and reading, and provide feedback to national governments for how they can improve their educational system.

Migration

As such, the Romanian labour market is confronted with multiple challenges, and one major problem is precisely the continuous reduction firstly in terms of volume of workforce and secondly of quality and availability for work. We are more than ever at a crossroads, 15 years after the beginning of the largest migration of Romanians since World War II.

It was in 2002, two years later after the official start of negotiations for EU accession that Romanian citizens acknowledged the first fundamental benefit of the EU — freedom of movement between member states due to the lifting of visa requirements for Romanian citizens. Overnight, queues at EU embassies in Bucharest disappeared, replaced by queues at the premises of the regional employment agencies for interviews with Spanish or Italian employers interested in attracting Romanians to take temporary jobs in agriculture.

Skilled and non-skilled people, among them teachers, accountants, technicians, engineers and economists made redundant by a bankrupt economy or paid too little to make a decent living started to apply for jobs in Italy or Spain, the countries most attractive for Romanians due to language affinity and the welcoming attitude of their populations.

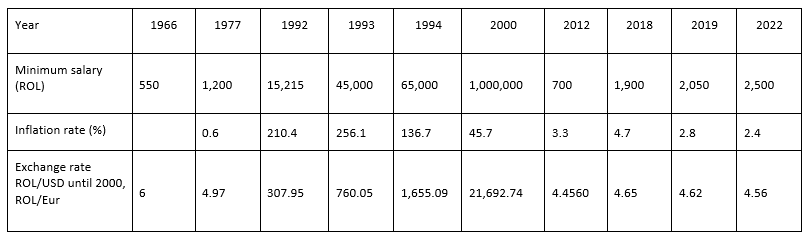

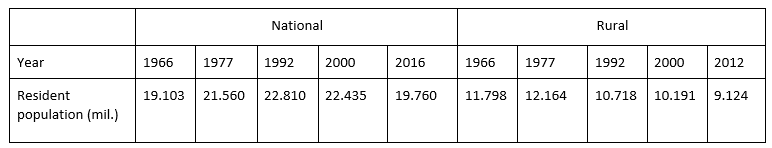

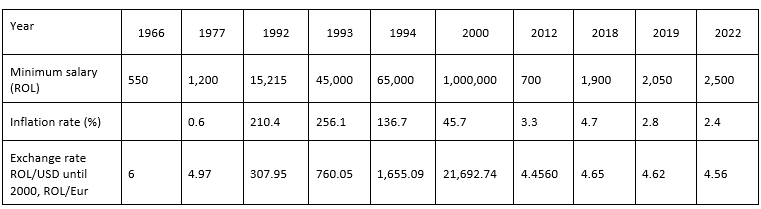

It was the start of a huge migratory wave, probably the largest of Romanians during peacetime. With half of the population living in rural areas, with an economy virtually bankrupted in 1999 after ten years in a row of hyperinflation, with scattered agricultural land ownership not allowing people to make a decent living out of it, at the beginning of 2000, the Romanian population was in a desperate situation. The minimum salary was for years around 50 euros per month, with the cost of basic food often considered comparable with that in developed countries. In addition, prices for daily utilities were also seeing a sharp increase due to the rising international prices of raw materials and liberalisation of domestic markets as part of the transition to a market economy.

For comparison, in 2002 – when visa restrictions were lifted – work picking strawberries in Spain, after deducting related expenses, was paid at around 500 euros per month net, 10 times more than the minimum wage in Romania. The calculation was simple, instead of working for the minimum salary in Romania with no labour contract thus no protection, it became more attractive to work abroad for three months in agriculture and earn an entire year’s average salary.

Until Romania officially became an EU member (on January 1, 2007) the targeted work places were mainly in agriculture and low value added services. After integration, the migratory wave started to include huge numbers of skilled people due to the recognition of Romanian qualifications in all EU countries.

In 2014, in compliance with the Integration Treaty, remaining labour market restrictions for Romanians were lifted by Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, France, Malta and the United Kingdom. At the end of 2017, according to the National Statistics Office of the UK, the number of Romanians working in the country amounted to 411,000, the second largest group after Poles (who numbered one million).

Remittances

The UN estimates that, as of 2017, around 3.58 million Romanians had emigrated to developed EU countries since 2000, especially Italy and Spain. In addition, working age emigrants exceeded 2.65 million persons, accounting for about 20 per cent of the Romanian working population. Their remittances in 2016 amounted to 1.9 per cent of GDP from a peak of 4.5 per cent in 2008. The World Bank estimates that Romanians who now live and work in other EU countries have sent home during the past ten years of EU membership over 52 billion euros, which also significantly contributed to raising the living standard of their families back home, especially in rural areas and small towns, and also improving country’s balance of payments.

What was considered a relief back in 2002 and at the same time a survival alternative to alienation for people living mostly in rural areas and small towns has a high probability 20 years after, to hit back and become a major loss for Romania. Not only have emigrants not returned home, but they eventually took their families with them to their adopted countries. The decrease in remittances from 4.5 per cent to 1.9 per cent of GDP over the past 10 years might reflect on one side the increase of GDP and the impact of the financial crisis on Western countries, especially Spain and Italy where the majority of Romanians are working abroad, as well as the fact that families joined Romanian emigrants in their adoptive countries. Brain drain became the new reality. It is estimated that as of 2013, around 14,000 physicians were working abroad representing 26 per cent of the total Romanian physicians with more than 50 per cent of those being younger than 40.

Rural areas and small towns are now depopulated, those 3.58 millions of Romanians from UN statistics were mainly from the areas most affected by the closure of entire industries such as mining, chemical processing , metal processing, defense, aeronautics. Considering the 3,000 communes of Romania, on average almost 1,200 people left their home village / town to live a better life in Western Europe. Localities with around 5,000 – 6,000 inhabitants lost around one third of their population. The negative effects could be seen everywhere, from schools without pupils, to tens of unhabited houses, increasing the school drop-out rate due to the fact that children were left home with no parental supervision.

Unrealistic targets

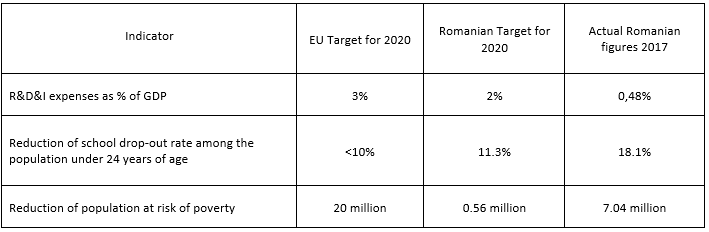

In March 2010, the European Commission published the Europe 2020 strategy for a sustainable development of the EU until 2020, thus establishing economic, social, educational and environmental protection priorities and associated indicators. Consequently, member states were invited to draw up their development strategies in the context of Europe 2020 and decide on their own indicators.

Restructuring the economy through massive closures was a painful process and we are now witnessing the consequences. It has been a tragic experience for people in their forties and fifties in a country with limited job offers, almost impossible to find a new, reliable work place in the same geographical area and during a period when new investments were scarce. Consequently, many of those people who became unemployed following massive lay-offs after being paid a certain amount as compensation no longer registered with unemployment offices which have long been passive with respect to implementing active labour market policies.Romania has a longstanding tradition of adopting ambitious and unrealistic strategies which can never be implemented. Each Europe 2020 target indicator was relying on its own strategy and action plan adopted during 2012 – 2013, but the current numbers in the table above show precisely the failure to achieve targets in the field of education, with major discrepancies between the target for school drop-out rate reduction, population at risk of poverty and the investments in R&D&I sector.

An important relief came from the fact that almost 50 per cent of the Romanian population was and still is living in rural areas where each family owned a house and some land which might be enough to suffice for the daily meal but not pay for a child’s education or for sustaining basic needs such as the rehabilitation of homes (thermal insulation), water adduction and sewage works, healthcare, cultural activities or vacations.

The unemployment rate did not reflect the reality. Instead of registering a record high number of job seekers or long-term unemployed people, the government allowed redundant workers to become retirees.Due to a lack of proper infrastructure, the high cost of transportation and the low level of salaries, commuting to neighbouring towns in search for a job was not an option in the absence of any governmental support. People were thus blocked in their small towns or villages with no income, contemplating their skills fading out with no hope in finding new jobs not only because investments were poor in the areas most affected by industrial restructuring but also because they no longer had the skills required by the new labour market.

The informal economy

In the 1990s, almost three million jobs disappeared in declining industries (mining, metal processing, chemical and rubber, agricultural machinery, trucks, heavy equipment) replaced by only one million mostly in trade, agriculture and services. The informal economy (grey economy) started to register overwhelming dimensions offering no protection to the people involved, especially in services and construction.

A report by the Romanian Academy shows that for the year 2000 the level of informal economy represented around 30 per cent of GDP, composed mostly of tax evasion (VAT) and unregistered labour. Among the main determining factors for the high rate of informal work was the excessive level of taxation on direct labour and of social contributions considering the very low level of salaries (e.g. the tax on a salary was 40 per cent in comparison with the 10-16 per cent at present for an average salary of 100 euros). On the other hand, the number of people officially employed with the minimum salary increased significantly, with the difference payed informally.

The very low minimum salary and the significant number of people earning that income keeps the risk of poverty very high for around 40 per cent of Romanians. According to Eurostat, Romania had in 2017 the highest risk of poverty among employed persons with 18.9 per cent, followed by Greece with 14.1 per cent and Spain with 13.1 per cent. The EU average was 9.6 per cent.

Little progress

In its report on the 2018 Convergence Programme of Romania issued in May this year, the Council of the EU stated that Romania has substantial unused labour potential, and several groups such as young people, Roma, the long-term unemployed and people with disabilities have difficulties in accessing the labour market. In the past year, Romania made little progress addressing the country-specific recommendation to strengthen targeted activation policies and integrated public services, focusing on those furthest away from the labour market.

Despite increased financial incentives for mobility schemes, participation in active labour market policies has remained very low, and the administrative burden has been high. A mechanism to match active labour market policies with the demand for skills is not yet in place, and the capacity to anticipate future skills needs and estimate the expected impact of new technologies is weak. Vocational education and training remains a second choice option and is not sufficiently aligned with labour market needs and regional or sectoral specialisation strategies. Those most affected remain the rural population and people living in small towns which were for a long time mono-industrial, whose sole major employer either closed or substantially contracted (e.g. mining regions).

In conclusion, caution is needed when reading statistics related to unemployment, because the many unemployed people who are of working age but lack skills are not included in them. But it would be difficult to imagine that people could become active on the labour market without basic, elementary skills such as reading, writing and understanding the principles of science. Reducing the school dropout rate in parallel with the improvement of PISA results should become top priorities for any educational reform. Local authorities could play a pivotal role in the transition of young people to employment by providing them with temporary work in order to hone their skills and support their return to full-time education or integration into the private job market. It is never too late to do something meaningful and educate the children of today for the labour market of tomorrow.

—

The views expressed in this opinion editorial are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Emerging Europe’s editorial policy.

Add Comment