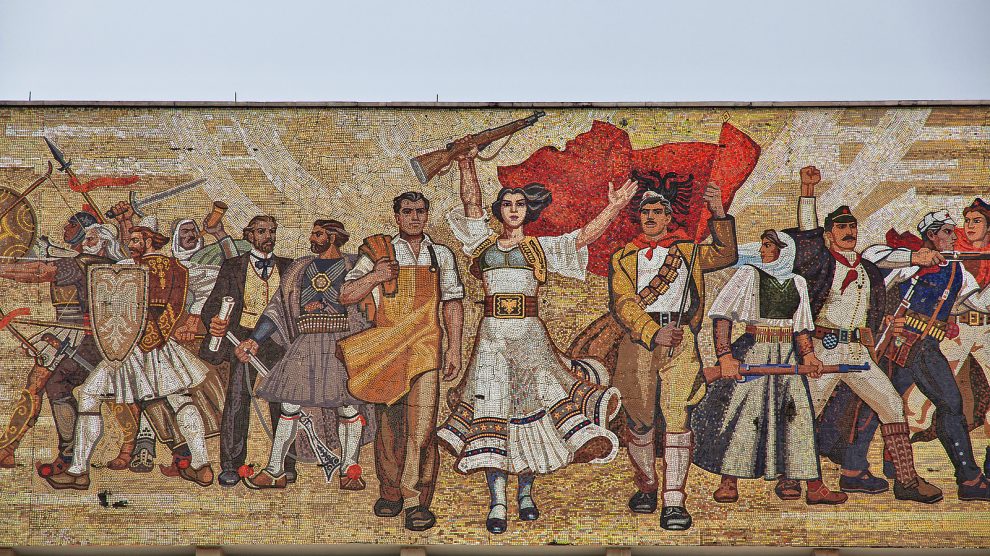

Albania on the cusp of change, chaos and civil war is the setting for the best memoir to emerge from the Balkans in decades.

In March 1991, journalists from Italian TV station Rai Uno arrived in the city of Durrës, Albania, to cover the country’s first free elections.

Walking around the city’s port they encountered a group of children. One of them, Lea Ypi – then just 11 – offers to translate for them. They decline her offer. Instead, they interview her.

“When I’m grown up, I want to be a writer,” she tells them. “It’s because I really like it. But being president is also not too bad.”

- Migrants are not weapons: Stop viewing them as such

- Forget the French Riviera, the Albanian coast is the next big thing

- Built to ward off invaders who never came, Albania’s bunkers endure

Ypi is not president of Albania. Well, not yet at least. But at a time when the life behind the Iron Curtain genre had begun to feel as though it had long passed its sell-by date, her writing has given it new impetus by offering us not just a chronicle of Albania’s transition from communism to (a resemblance of) democracy, but a deeply personal and oftentimes hilarious book that it is the most remarkable memoir to emerge from the Balkans in decades.

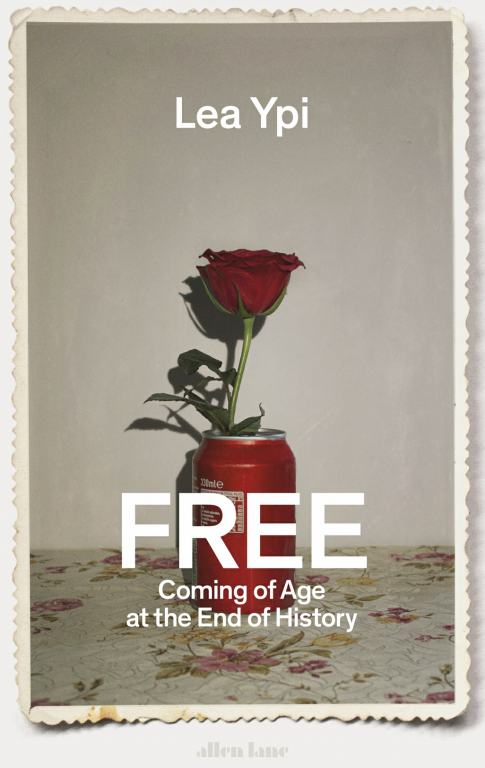

Free: Coming of Age at the End of History is refreshingly free of the hindsight that blights so many other, lesser works.

Ypi makes no claims to have known that the Albanian communist regime was set to collapse. She happily admits that as a child in a country that was on the cusp of enormous changes, she was a true believer until the very end – as only the very young can be.

This is best demonstrated in the book’s opening, when, on a school trip to the capital Tirana, she rushes to hug a huge statue of Stalin in the city’s central square, only to discover that pro-democracy protesters have already lobbed off the head of the former Soviet dictator, “magnificent moustache and all”.

Nora, her teacher, blames hooligans. Confused, when young Lea arrives home she asks her father what “hooligans” are.

“He clarified that hooligan was a foreign word for which we had no Albanian translation. We didn’t need it. Hooligans were mostly angry young men, who went to football matches, drank too much and got into trouble, who fought with supporters of the other team and burned flags for no reason. They lived mostly in the West, though there were some in the East too, but since we were neither in the East nor the West, in Albania they hadn’t existed until recently.”

Reklama! Reklama!

Much else didn’t exist in communist Albania: Coca-Cola cans for example, which we find out were markers of social status. If people happened to own a can, they would show it off by exhibiting it in their living rooms, usually on an embroidered tablecloth over the television or the radio, often right next to the photo of Enver Hoxha, the country’s dictator from 1946 until his death in 1985.

A couple of years later on a trip to Greece, Ypi is presented with an unprecedented bounty of Coca-Cola: in both cans and plastic bottles. She devours them; not out of greed, but simply to try and find out which tastes better.

Yugoslav TV, available when the wind was blowing in the right direction, provides a break from the monotony of Albanian programming. The adverts were an Ypi family favourite.

“If it was a commercial for personal hygiene, [my father] would immediately shout: ‘Reklama! Reklama!’. My mother and grandmother would drop whatever they were doing in the kitchen and sprint to the living room to catch the last sight of a beautiful woman with a delightful smile on her face who showed you how to wash your hands.”

Days after Ypi’s visit to Stalin’s headless statue, Albania’s rulers declared the country a multiparty democracy. Immediately, her parents state that they had never supported “the Party”, had never believed in its authority, had never loved “Uncle Enver”.

She can’t hide her disappointment, writing: “they had simply mastered the slogans, and gone on reciting them, just like everyone else, just like I did when I swore my oath of loyalty in school every morning. But there was a difference between us. I believed. I knew nothing else.”

Graduating and dropping out

But Ypi’s parents had been hiding a lot more than a disdain for Uncle Enver.

Xhafer Ypi, a prime minister during the fascist Italian protectorate of 1939-43 and a constant source of shame for young Lea – “Why do we have to share a name with a fascist?”, she constantly asks – is revealed to be her great-grandfather. Her grandmother, from a wealthy property-owning family, also has an undesirable “biography”. As a consequence, her parents are unable to join the Party, unable to take jobs worthy of their abilities.

Other relatives, friends, neighbours are described as having “gone to carry out research at university”. Some stay as long as 15 years before “graduating”. Others “drop out”. Some become “teachers”.

We know these are all euphemisms, but when the full explanation comes, it’s still a punch in the gut. University is prison. Different subjects of study corresponded to different official charges: to study international relations meant to be charged with treason; literature stood for “agitation and propaganda”; and a degree in economics entailed a more minor crime such as “hiding gold”.

Graduating meanwhile meant being released, dropping out suicide. To make the move from student to teacher is to become an informer.

The book loses a little steam after that, but the drama returns as Albania descends into civil war in 1997, when its myriad pyramid schemes collapse. Ypi’s parents are among the hundreds of thousands of people who lose most of their savings.

Ypi today is a professor of politics at the London School of Economics, and one of her most pointed remarks is not about pyramid schemes, Uncle Enver, Stalin or the Party, but the indifference and at times brutality shown by the West towards Albanians trying to flee the chaos: pertinent given what is currently taking place on the border of Poland and Belarus.

“Were borders and walls reprehensible only when they served to keep people in, as opposed to keeping them out?”, she asks, before suggesting that: “the border guards, the patrol boats, the detention and repression of immigrants that were pioneered in southern Europe for the first time in those years would become standard practice over the coming decades.

“The West, initially unprepared for the arrival of thousands of people wanting a different future, would soon perfect a system for excluding the most vulnerable and attracting the more skilled, all the while defending borders to ‘protect our way of life’.”

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.