It’s not an exaggeration to say that Belgrade is a very artsy city. Museums and galleries dot the map, all constantly displaying art new and old.

So, when a friend told me about a new street exhibit taking place on the evening of March 6, I expected little out of the ordinary.

But, as we were waiting, in the bitter cold, with a group of people in a little alley behind the towering Dom Sindikata concert hall, it was clear this event was anything but ordinary.

In fact, it was an exhibit organised by Art Brut Serbia Association (ABSA) to showcase pieces made in their Art Brut Studio VMA, a unique collaboration between the art world and the psychiatric health system.

The exhibit kicked off with a performance by the Choir of Persons with Laryngectomy of the famous Serbian patriotic song Tamo Daleko. This set the tone for the rest of the evening. A little off kilter, but humanising and centering those who are often unseen as well as unheard.

Art Brut is a French term, denoting outsider and marginalised art and artists. It was first brought into mainstream discourse by artist Jean Dubuffet in 1945. Nearly three decades later the English equivalent “outsider art” began to be used. Regardless of the terminology, this type of art is mostly created by people with no formal training and outside of the fine art establishment.

The Art Brut Studio VMA started in 2015 at the Military Medical Academy (VMA) where twice a week the group psychotherapy space is transformed into an atelier in which day hospital patients and members of the “Healed Psychosis Club” use a technique called “deep drawing” to create stunning works of art.

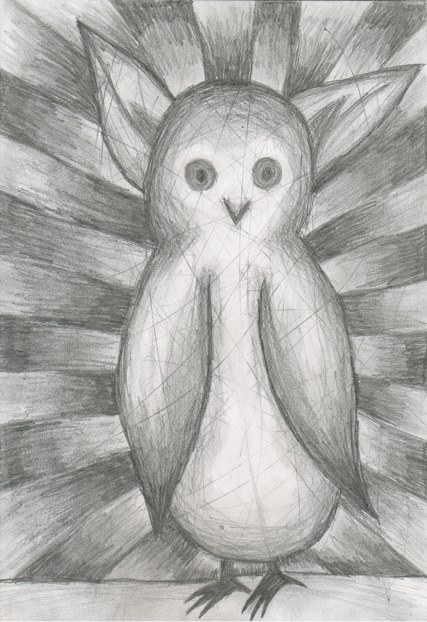

Art therapy has long been a staple of mental institutions across the world. But what was exhibited that night and for the following two weeks were not the kitschy arts and crafts you might expect.

Instead, there was a unique glimpse into the psyche and creative potential of people who are often overlooked and marginalised in wider society. The art is bold and deeply personal and openly discusses the issues that the mentally ill face both within and without.

Patients of mental hospitals still must contend with a strong stigma in Serbian society. Most still consider mental illnesses shameful and a sign of weakness.

Some weeks later, I caught up with Goran Stojčetović, the founder and president of ABSA, to learn more about the unique way in which art can help make marginalised people feel more connected and valued.

Mr Stojčetović is a classically trained artist with a degree in painting from the Faculty of Arts in Prishtina. He works at the National Theatre in the same city as a set designer.

“The idea to establish Art Brut Serbia Association came from a sense of valuing the creativity of people outside the system in a time of a destabilised psychological condition of both individuals and society,” Mr Stojčetović says.

“The association seeks to reexamine the concept of normality and show how important this kind of creativity is. Additionally, the association works to discover new, ‘invisible’ artists and include them into the social, artistic, and cultural spheres of life,” he continues.

The work of ABSA often includes stigmatised and invisible people. In addition to mental patients, the association has worked with children and youths with intellectual disabilities, refugees, and convicts. And also anyone else who feels, as Mr Stojčetović puts it, fed up with official culture and art.

Mr Stojčetović points out how valuable and transformative these art workshops can truly be.

“Often after our creative workshops, repressed creative personalities are awakened that help people to experience life more flexibly. Creativity is the psychological base that gives the individual a harmonious way to solve problems. Also, their social communication skills and senses of belonging and being valued are strengthened,” he explains.

The project that ABSA has maintained with the VMA for the last five years is the only one of its kind not just in Serbia, but in the Balkans.

And it’s producing significant and quality art, too.

“Out of the several hundreds who went through the studio in the last five years, dozens have left pure masterpieces of artistic expression. The authors, and the drawings themselves, are then included into the activities of ABSA where they can continue developing their creativity outside of the hospital with a clear direction toward resocialisation and destigmatisation,” Mr Stojčetović tells Emerging Europe.

But, it seems that VMA is for now alone in showing real and concrete interest in this kind of work. Mr Stojčetović believes that the government and institutions could do more.

“It’s a general problem of this society because the government does not finance long-term scientific and artistic projects and experiments,” he says.

Regardless of the lack of financing, the work of Art Brut Studio VMA continues, with patients discovering their creative potential as a possible way toward healing and overcoming their problems.

—

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.

Add Comment