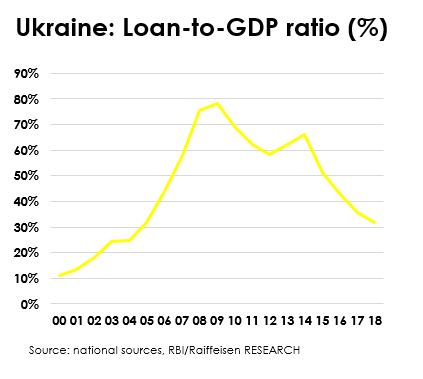

The Ukrainian banking market is probably the most dramatic boom-bust story in the CEE region. From 2000 onwards, the ratio of loans to GDP rose from around 10 per cent to almost 80 per cent (2008-09). During this time, many foreign and western banks tried to get involved in the local credit boom. The development was neither sustainable nor was it feasible to refinance such a boom locally. This assumption also confirms the fact that the loan-to-deposit ratio rose to almost 200 per cent by 2008-09.

With the deep economic crisis of 2008-09, the boom ended abruptly, and the unsustainable expansion then manifested itself in a non-performing loan (NPL) ratio of 30-50 per cent (depending on the calculation method). After 2008-09, there were drastic changes in the Ukrainian banking sector. For the first time, the debt load was urgently reduced, and the loan-to-GDP ratio began to fall. From 2010 onwards, many western foreign banks turned their backs on the difficult market or the mass market business (among them notable players like Home Credit Bank, Renaissance Capital, SEB, Swedbank and Erste Bank). Foreign banks slashed their cross-border exposure towards Ukraine from some 53 billion US dollars (September 2008) to around 30 billion US dollars in 2012. Currently, this figure stands below 10 billion US dollars. The loan-to-GDP ratio currently stands at a lowish 30 per cent (roughly the same level as 2003-04).

The deep and conflict-induced economic crisis of 2014-15 further accelerated the necessary restructuring and reorientation of the Ukrainian banking sector. Moreover, since then, the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU), which, with the support of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), is an anchor point for far-reaching institutional reforms, has been pushing in the direction of decisive structural changes in the banking sector. This can be seen from the rapidly declining number of banks operating on the market (down from close to 200 a few years ago to 76 as of June 2019).

More important than the mere reduction in the number of banks was the associated closure of so-called “circuit banks” or “pocket banks”. The existence of such market players may lead to distorted market prices and may favour the execution of dubious or illicit transactions. The clean-up activities culminated in the emergency nationalisation of Privatbank in late 2016. The biggest Ukrainian bank (with a market share above 20 per cent of total assets) was recognised as insolvent and heavily involved in related-party lending. In summary, Ukraine is a sad record holder in terms of the number of banking sector crises in CEE and even among emerging markets globally. In Ukraine, at least three or four severe banking crises have taken place since the 1990s (in some cases accompanied by currency and sovereign debt crises). In this respect, it can be said that the country was hit by a severe banking crisis every seven years on average.

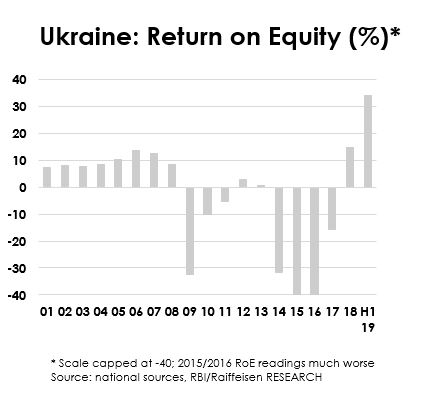

Since 2017, or 2018 at the latest, however, the tough restructuring has borne fruit. Aggregated, the Ukrainian banking sector was profitable again in 2018 for the first time since 2013. In 2018 the sector was printing an average Return on Equity (RoE) close to 15 per cent, being one of the most profitable markets in the CEE region. In H1 2019 the Return on Assets was around 4.2 per cent, while the RoE averaged 34.3 per cent. Moreover, all banks have now disclosed their ownership structure, completed recapitalisation programmes and reduced their exposure to related party risks. IFRS and Basel III standards are implemented and risks to financial stability are at their lowest level in history according to the NBU. It should be noted, however, that the banking sector would have to write profits at current levels for at least six-eight years to compensate only for the losses of the crisis years. In the past, such a long period of stability was hardly imaginable in Ukraine.

However, the chances of more than seven years without a financial crisis are better this time than ever before in view of the institutional reforms in banking sector oversight and regulation as well as the restructuring and debt relief of recent years. But there is still a lot to be done. To achieve a similar degree of consolidation as some other banking sectors in the region, only 35 to 50 larger and/or nationwide banks operating in the country would probably be needed. In this respect, there are possibly still a few bank closures or mergers pending on a consolidating market.

The key question will be which market participants could be among the driving forces here. Besides the largest western foreign banks (Raiffeisen and BNP, with market shares of three-five per cent) some other foreign players are still in the market (such as OTP, ING, Citi, Credit Agricole). That said, on aggregate western banks still hold a market share of 15-20 per cent. Russian banks close to the state will certainly not want to expose themselves or will probably not be allowed to expand drastically. However, Alfa Bank (one of the largest private commercial banks in Russia) seems to feel good in Ukraine with a market share of close to four per cent. And the attractiveness of the market is not to be underestimated. There is considerable scope for sustainable growth in Ukraine. Loans to households are at extremely low levels or around five per cent of GDP. In many comparable CEE countries this ratio is at least 10 to 15 per cent of GDP. And should the NBU also succeed in sustainably lowering inflation and thus lending rates, there would be scope for double-digit credit growth rates in the case of sustainably rising levels of prosperity.

So, the crucial question is how sustainable the deep institutional reforms in the country and the banking sector really are. If a new start is made after the numerous crisis years, a development like that in some CE/SEE countries is conceivable. Here, the 1990s were partly marked by severe banking crises (such as Bulgaria or the Czech Republic), while the 2000s were a success story in many previously hard hit countries – also for foreign banks, which have ventured into these markets across the board, especially since the beginning of the 2000s. Western foreign banks currently have market shares of 60-80 per cent in many CE/SEE markets (including the Czech Republic and Bulgaria), while the market share of western foreign banks in Ukraine remains a fraction of that. And in the CE/SEE countries, western banks have ultimately also speculated on and profited from a comprehensive institutional process of deep reform and transformation – even though one never knows exactly whether such a process can succeed.

Detailed figures and information on the Ukrainian banking sector can be found in the recently published CEE Banking Sector Report. You can find Raiffeisen Research’s CEE Banking Sector Report on the research portal.

(Please note that – in order to fulfil the legal and regulatory requirements – you must register to access the portal.)

This article – which was first published at Discover CEE – was co-authored by Mykhailo Rebryk, PhD, chief macroeconomic analyst at Raiffeisen Bank Aval in Ukraine, who closely monitoring the local banking market.

Add Comment