Belarus first held a presidential election 26 years ago. Since then, an entire generation of Belarusians has grown up knowing just one president, reading schoolbooks which carry the portrait of just one person: Alexander Lukashenko. But are there other important political figures in Belarusian history except Lukashenko? How do teenagers find out about elections? What information is not found in the country’s schoolbooks? With the country’s next presidential election – set for August 9 – fast approaching, we take a look.

Schoolbooks for Belarusian 11th graders describing the independent period of Belarus start with the Belovezha accords and the adoption of the Constitution in March 1994. There then follows a major biographical reference about Alexander Lukashenko, including his portrait. Students are told that the country’s first democratic elections were held in 1994, and that Lukashenko won in the second round, with the support of 80.3 per cent of voters.

Information about the other candidates in these elections, what Lukashenko’s electoral programme was and why there was a second round is omitted. They are questions left without answers.

Teens are told about referendums which took place in 1995 and 1996. According to the book’s authors, the first was held because many Belarusians had expressed their dissatisfaction with the country’s symbolism, “which was used with the agreement of an enemy power on the territory of Belarus occupied by Nazi troops during the Great Patriotic War”. That’s why we currently have the red and green flag and Soviet-inspired coat of arms as opposed to the white-red-white flag and Pahonia coat of arms.

The second referendum ended the confrontation between the executive and legislature, whose imbalance could have provoked a political crisis. Moreover, an unknown group of MPs (there is no specification in the book) had begun to restrict the president’s credentials. No attempt is made to hide the fact that “there was a significant personification of power in the president”, but this is presented as being exclusively positive.

There is also information about elections in 2001. Students can read that there was as an alternative because there were three candidates (who they were, with the exception of Lukashenko, is not mentioned).

Finally, 2004 – and one more important happening. As a result of a vote, the statement that the same person cannot be elected to more than two presidential terms was excluded from the Constitution. It became “an evidence of the strengthening of the interior political situation of the Republic of Belarus, the unity of its people at the turn of the 20th century”.

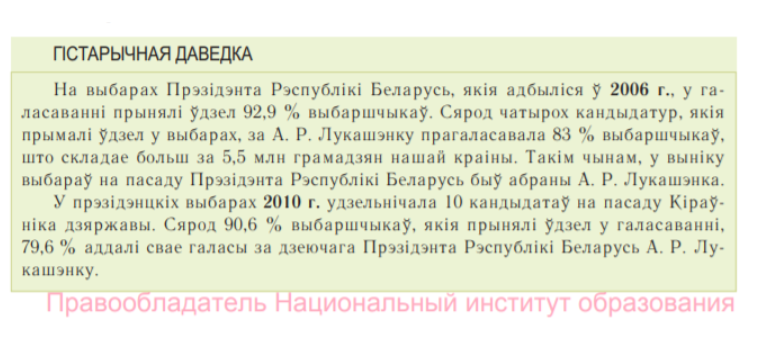

Information about subsequent presidential elections is included in the short reference box shown below. Once again, other candidates are not named.

Why Belarus has had the same president for such a long time is explained to students. Lukashenko changed country’s destiny substantially after being an initiator of several referendums which rewrote the Constitution. It seems that everything is clear. But if you are a good student there should be questions which remain unanswered. It is worth parents showing that paragraph to kids and asking themselves: do you remember history in detail?

If we believe the schoolbooks, the elections were perfect. Was that really so?

The elections of 1994 were the first and, until today, the last which were declared as free and fair by the European Union and the US. Lukashenko bypassed his second round competitor – the then prime minister Viachaslau Kebich – with big advantage.

The following elections were held seven years later, although according to the Constitution the president of Belarus is elected every five years. The point is that with the help of the referendum of 1996 Lukashenko reset his presidential term. Counting began anew.

That year also Lidia Ermoshina appointed as head of the Central Election Committee (CEC). This year she will be counting the votes of Belarusian people for the fifth time.

The previous head of CEC, Viktar Hanchar, who did not approve of the changes made by the referendum, was removed from his position. He then went missing in action in 1999. Yes, people were disappearing during the 1990s in Belarus – and it should be written in schoolbooks.

But let’s go back to elections. All of them, starting from 2001, have seen irregularities. There have being searches of the candidates’ headquarters, pickets, and voters have actively been summoned to take part in early voting. Independent observers have been unable to watch the procedure of vote counting. Here is a curious case for you: a dead man was invited to vote. What candidate do you think he would sympathise with the most?

Election experts also noted that most observers were acting on behalf of public associations and political parties that don’t oppose the current authorities. Do you really think that they are interested in checking how fair the elections are?

As complaints often were left without any answer, people expressed their anger through protest. That is how “Ploshcha” appeared – it is the national name for mass action which traditionally happens at Kastrychnickaya Square in Minsk (usually on election day).

Students should know that from 9,000 to 30,000 people (according to different estimates) took to the streets of Minsk before the final results were announced. Many Belarusians were sure that the elections would be falsified to ensure the desired outcome. After a while protesters put up tents in Kastrychnickaya Square. The camp lasted for three days before it was brutally dispersed by riot police

On election day in 2010 one of the candidates for president, Uladzimir Niakliaeu, was unable to reach the site of that year’s protest, being beaten by “people in black”. He had to be driven to hospital. The protest was put down by special forces who cleared the streets of people in just a couple of minutes. Hundreds of Belarusians were detained in prison, including other presidential candidates. Uladzimir Niakliaeu was taken in to pre-trial detention straight from hospital.

There were no such mass protests in 2015. Two factors influences it: revolution in Ukraine which calmed down the protest mood in Belarus, both by its proximity and the amount of blood spilt, plus the disappointing end to the two previous Ploshchas. Voting irregularities still took place.

That’s how it happens: the authorities declare democratic elections but international observers have a lot questions about them every time. It has also become usual for Belarus to come under sanctions from the EU and the US. Some of the sanction apply to officials, such as bans on entry to several countries, but some restrict the economy of the whole country, and the lives of ordinary Belarusians.

Will the elections of 2020 follow the same scenario? Or will they differ?

The main difference in the upcoming elections is that people who have never before taken part in politics have become involved in the presidential campaign. Ex-banker Viktor Babaryka, one of the founders of the Belarus Hi-Tech Park Valery Tsepkala, and YouTube blogger Siarhey Tikhanovsky (who was later replaced as a candidate by his wife, Sviatlana Tikhanovskaya) made a statement about their political ambitions. These people don’t belong to the traditional opposition.

Also, these elections stand out because a number of potential candidates ended up in jail even before they became official candidates. For example, Siarhey Tikhanovsky ended up in prison on May 29, Viktar Babaryka and his son were arrested on June 18 and on June 29 Valery Tsepkala was accused of illegal activity (though it didn’t lead to his detention). This has never happened before – even in the years of the mass protests, candidates ended up in jail only later.

One more difference: in past elections the main strategy of the opposition has been to organise protests after the results are announced. This time another strategy was chosen – to fight for free and fair elections.

Viktar Babaryka’s team actively collected signatures of Belarusians who wanted to become a part of their precinct election commissions in order to be able to count the votes personally. The initiative was named “Honest People”.

More than 2,000 Belarusians applied – a record number – but only 12 were elected to precinct commissions. Five to polling stations in Belarus, and seven to embassies abroad.

This is only a small part of what is going on. We should mention a mass brawl with riot police in the centre of Minsk (for the first time since 1996), people being arrested for just passing by, TV hosts being dismissed for declaring their position on social networks, and the signatures which have to be collected by candidates being declared ineligible, meaning that they cannot stand.

In addition, the election campaign is being conducted with women at the forefront for the first time, although Lukashenko recently said that our Constitution is not made for women. Now Sviatlana Tikhanovskaya is a candidate for president instead of her arrested husband, Maria Kalesnikava – the head of Viktor Babaryka’s team – became his frontwoman, and Veranika Tsepkala suddenly stepped forward in place of her husband. When it became clear that only one of the women could be a candidate, they united behind Tikhanovskaya. This is important because never before have opposition candidates united behind a common goal.

This presidential campaign will definitely deserve a dedicated paragraph in future schoolbooks, if they will be written by honest authors.

—

This article was co-written by Sviatlana Belaus, editor of Rebenok.by. It was first published at Rebenok.by and is reproduced here with permission.

—

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.

Add Comment