Vuk Stefanović Karadžić, the Serbian linguist and philologist, credited with standardising the Serbian language was no stranger to controversy. For including swear words in his dictionary, he received an anathema from the head of the Serbian Orthodox Church. But it’s a collection of erotic folk poems, not published during Karadžić’s time, that would prove his most controversial contribution to Serbian literature.

Standardising the Serbian language was no easy feat in the latter half of the 18th and early 19th century.

Written Serbian at that time had no firmly agreed-upon rules and borrowed much from Serbian and Russian Church Slavonic, creating a divide between the clergy and nobles on one side, and the common people on the other.

- Who owns Nikola Tesla?

- Serbian World — a dangerous idea?

- Hunyadi epic Rise of the Raven will be Hungary’s most expensive TV show

Vuk Stefanović Karadžić’s radical (for the time) idea was to distance the Serbian language from the church and standardise it based on how ordinary people spoke.

But his commitment to folk culture and creativity went far beyond his language work.

Like other linguists and philologists of the time, Karadžić also collected the stories, fables, and poems that were previously part of oral tradition and passed on through song and storytelling.

Thanks to these efforts, the epic poems that now form the backbone of Serbian culture and literature were saved from oblivion and took their rightful place as objects of serious literary analysis.

At the same time that he was collecting epic poems about the Battle of Kosovo, however, Karadžić was also chronicling a much more risqué kind of poem that he called “special”.

What was so special about them? The fact they are totally explicit in a way that contemporary audiences may not expect folk songs from around two hundred years ago to be.

The Monk and Mara

Among the hundred or so songs gathered, subjects as premarital sex, adultery, and even voyeurism are broached with surprising frankness and humour.

Consider The Monk and Mara, which describes a forbidden tryst between the two titular characters, or a poem about girl sweeping the street while exposing her “pride”.

Literary audiences had to a wait a long time to actually read these works, however. The manuscripts were discovered after Karadžić’s death in 1864 in the archives of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts (SANU) and were not published until 1974. Even then only a small selection were published, and only 500 copies of the volume printed.

It bore a disclaimer saying that it should only to be used for “scientific purposes”.

Five years later, the publishing house Prosveta finally brought all of the poems and songs to the public, in a volume titled Crven Ban (the title of one of the poems and an allusion to a phallus which the book’s cover made plainly obvious). Prosveta did not ask the SANU for permission before publication.

All in all, it took more than one hundred years for this special type of folk wisdom to be finally shared in print.

Why Karadžić decided not to publish them during his lifetime remains a mystery, but if including a few swear words in a dictionary was enough for an anathema from the Serbian Orthodox Church, one can only imagine what a full volume of erotic poetry could have triggered.

Historical importance

A broader question remains, however. Are these explicit poems valuable in any other way than just humour and shock value?

Serbia’s online tabloids seem to rediscover Crven Ban every few years with renewed awe and excitement over the fact that people living 150 years ago knew what sex was (and, furthermore, enjoyed it).

Just like the epic poems of the Kosovo Cycle reveal a lot about Serbian history, culture, and the Kosovo myth itself, so the poems collected in Crven Ban offer a rare glimpse into the lives of ordinary people.

As such, it’s an invaluable record of social history, a history that goes beyond leaders, conquests, and battles to reveal what life actually looked liked in the past.

Crven Ban reveals a much more relaxed attitude to sex, especially female sexuality, than one would think based on the records maintained by the church and the nobility.

Historically, Crven Ban also drives home the differences between the ruling classes of the time and ordinary people. It wasn’t just the dialect of the language that was different, but their worldview and culture too.

Like the rest of Karadžić’s work, collecting erotic poems was another way to amplify the voices of common people and prove that culture doesn’t just happen at monasteries and within the intelligentsia: is something that belongs to everyone.

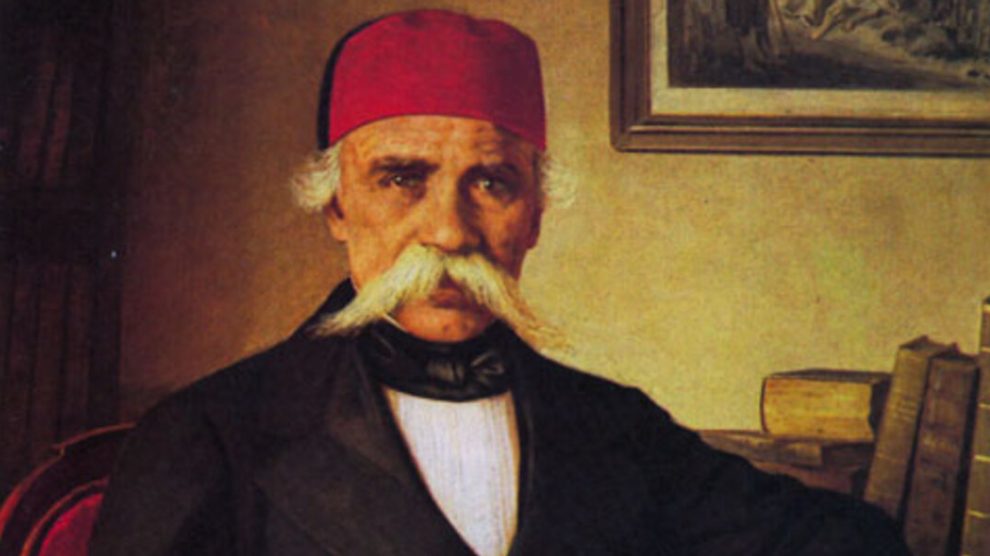

Photo: Vuk Karadžić (Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain).

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.