What will emerging Europe look like in 2100? This question has tentatively captured the imaginations of politicians, economists, and social scientists alike for some time now, and all point to an overwhelming trend – a much more sparsely populated region.

While the decrease in size of some nations in the region – particularly Bulgaria – has been no secret for some time now, a new study from the medical journal The Lancet reveals that the threat of depopulation is far more pronounced than it appears, and must be met with thorough and foresightful governance.

The study forecasts population scenarios for 195 countries from 2017-2100 by anticipating age structures, resources, health care needs, and environmental and economic landscapes. Factors such as net migration, deaths from war, natural disasters, and the state of the economy were all taken into account. However, researchers found that the most influential variables stemmed from female emancipation: the rate of female education, and access to reproductive health services.

As with any forecasting, the study acknowledges that with the incorporation of these factors, there is lots of room for deviation, and uncertainty intervals (UI). Trends are merely tentative, and some factors will remain unknown and unseen. Furthermore, the data of the study is only as good as the qualities of previous data.

Nevertheless, according to the authors of the study, this allowance for various factors makes the results a lot more reliable than those of the United Nations Population Division (UNPD), which relied on non-causal time series models that do not include any covariates. Rather, The Lancet study’s data evolved with the changes in variables. Interestingly, this resulted in a much lower forecast of the global population.

According to the study, the global population is expected to peak as early as 2064, at 9.73 billion, and decline to as low as 8.79 billion by 2100 – 2.41 billion lower and 36 years earlier than previous forecasts.

So what does this mean for emerging Europe?

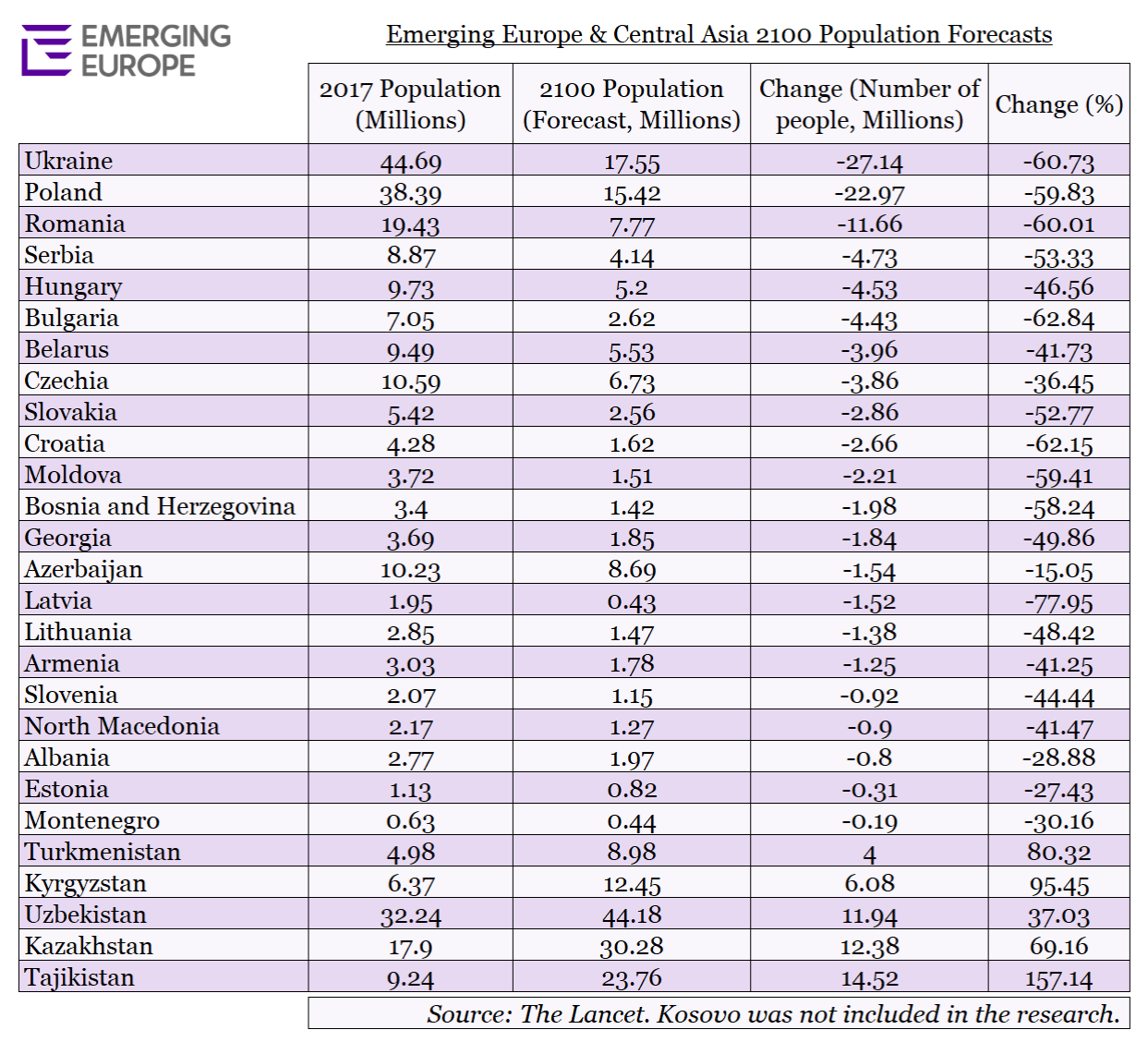

Emerging Europe’s analysis of the data reveals a massive 55 per cent decrease in the population of the region by 2100, from 185.35 million people to just 83.25 million. This extreme drop is somewhat anomalous with the global trend, for while the population of Europe as a whole is also expected to decrease, it is forecast do so by a much smaller 26 per cent.

This decrease will be felt most by the region’s largest countries. Ukraine is forecast to experience a 60 per cent decrease (more than 27 million people) to 17 million, Romania will also see a 60 per cent drop to just 7.77 million, while Poland will see its population reduced 59 per cent to 15 million.

Bulgaria’s population, which now stands at seven million (down from from 8.9 million in 1988), will drop even further to just 2.62 million, a 62 per cent decrease. In terms of percentage of population lost, Latvia will be the hardest hit in the region however, with a 77 per cent decrease that will see its 2.6 million people whittled down to just 430,000.

The trend is much the same across the region. Montenegro, Estonia and Albania will experience the smallest decrease, 27 per cent, still slightly higher however than the European average.

—

These changes in population will drastically impact demographics. The global age structure is forecast to shift to an ageing population, where 2.37 billion will be older than 65 and just 1.7 billion will be younger than 20. This trend is partially accentuated in regions that will experience the heftiest declines, such as emerging Europe.

This has been confirmed by another recent study, this time from, Eurostat on the ‘old age dependency ratio’ which compares the number of people over 65 to those of working age, 15-64. This dependency is expected to double by 2100 to 57 per cent, meaning that there will be fewer than two persons of working age for every person aged 65 and over. This will be highest in Poland at 63 per cent, yet generally, there is no a clear divide between the emerging Europe region and Europe as whole.

So what is causing this seismic change? The study explains that the main drivers are generally an increase in female education and access to reproductive health services. Yet other factors also play a part, such as immigration and mortality.

For the region, however, no one factor can be singled out as the main driver, underscored by a multiplicity of impacts.

An older, smaller population has huge ramifications throughout the social, political, and economic structures of society, and as The Lancet’s editor-in-chief Dr Richard Horton warns, it “charts a future we need to be planning for urgently.”

Labour forces will ultimately weaken, and economic growth is expected to decline, particularly as extra strain will be placed upon pensions, healthcare, and social support systems. According to the study’s authors, this will ultimately lead to higher taxation and further reduce economic growth and investment.

This shift in age structure is also expected to reduce innovation. However, not all hope is lost, as the study does mention that robotics are a promising wildcard for a sustainable low-cost labour supply that could change the trajectory of economic growth in high-income countries.

Moreover, the intrinsic relation between population makeup and economic health ultimately influences geopolitical power. This has substantial implications, where the European grip on geopolitical power is expected to weaken. The study also sees China becoming the top economic power by 2035, yet the title will return to the US in 2094. Nigeria is forecast to have the most significant rise in power, with its economy growing from 23rd largest in the world to ninth largest, as it will be the only economy in the world to actually see its working-age population grow.

This shift in global power will mean a lot for a region that frequently looks to the US and EU for geopolitical support.

“The 21st century will see a revolution in the story of our human civilisation. Africa and the Arab world will shape our future, while Europe and Asia will recede in their influence,” explains Dr Horton. “By the end of the century, the world will be multi-polar, with India, Nigeria, China, and the US the dominant powers. This will truly be a new world, one we should be preparing for today.”

With an ageing population, politics will also change at a more micro level. Broadly accepted trends of the elderly voting more conservative can further disenfranchise a more liberal youth, leading to a larger polarisation in political viewpoints – a trend that is partly already taking hold in nations like Poland, where the recent presidential election split age groups.

The study certainly paints a grim future for emerging Europe, and is likely to become a dominant policy concern. However, as Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation Professor Stein Emil Vollset, the first author of the study, warns, nations “must not compromise efforts to enhance women’s reproductive health or progress on women’s rights.”

Instead, researchers aim to highlight the importance of women’s sexual health, reproductive rights, and career support. The research rather aims to encourage a broader approach to population that is not purely determined by fertility. While having some impact, the reductionist solution of encouraging more women to have children is not only a problematic and patriarchal assumption of women’s role in society, but it is also scientifically misplaced as the best fix.

International Monetary Fund economist Alisdair Scott explains that “financial incentives in other countries don’t seem to have had much effect on birth rates. But even if they could, immediately, it would be two decades before a difference were seen in the working-age population – whereas the demographic pressures are here and now.”

Yet many of emerging Europe’s nations do not seem to heed this advice. Already aware of the problem, countries like Poland and Hungary seem to be applying the less-effective solution. Poland’s ruling party’s 500+ policy that offers financial incentives for women to have two or more children instead reinforces the outdated notion that the role of women is to be mothers.

Dr Christopher Murray, who led the research, warns that some countries may go so far as to restrict women’s access to reproductive services and contraception, which would have devastating consequences. “It is imperative that women’s freedom and rights are at the top of every government’s development agenda,” he explains.

Instead, the solution lies in a liberal immigration policy.

Professor Ibrahim Abubakar of University College London, and chair of Lancet Migration, explains that, “migration can be a potential solution to the predicted shortage of working-age populations,” continuing that this needs to rest on a fundamental rethink of global politics.

“Greater multilateralism and a new global leadership should enable both migrant-sending and migrant-receiving countries to benefit, while protecting the rights of individuals. Nations would need to cooperate at levels that have eluded us to date to strategically support and fund the development of excess skilled human capital in countries that are a source of migrants. An equitable change in the global migration policy will need the voice of rich and poor countries. The projected changes in the sizes of national economies and the consequent change in military power might force these discussions,” he says.

This solution entails a huge change of heart for many governments in emerging Europe, where nations like Hungary operate some of the strictest immigration policies in the world, and racial minority issues often propel the conservative end of politics. However, for experts, a liberal and globally coordinated approach is the answer.

“Ultimately, if Murray and colleagues’ predictions are even half accurate, migration will become a necessity for all nations and not an option. The positive impacts of migration on health and economies are known globally. The choice that we face is whether we improve health and wealth by allowing planned population movement or if we end up with an underclass of imported labour and unstable societies,” Professor Abubakar continues.

This liberalised approach to immigration will be crucial in the coming years for emerging Europe, if it wants to have any hopes of counteracting the negative socio-economic impacts of aging and decreasing populations.

This is particularly pertinent for a region that has of late experienced an exodus of people heading for Western Europe. Instead, a strengthening of institutions and an overall improvement of the economic and investment climate needs to play a role in offering reasons for people to stay, and others to come.

Depopulation will also bring positive developments, however. A smaller population means a lesser strain on the environment, as food production and carbon emissions will be far lower than previous forecasts – where the world population in 2100 was placed at 11.2 billion.

Moreover, while Emerging Europe’s data analysis reveals huge depopulation trends for the CEE region, the opposite was true of Central Asia. Instead, the region is forecast to undergo huge population growth, a 50 per cent increase, from 87.7 million to 131.97 million. This is primarily seen in Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Turkmenistan, which are all forecast to experience sizable increases, with Tajikistan’s population set to jump by as much as 157 per cent to 23.8 million.

With this shift in demographics comes greater geopolitical influence, an aspect that will be significant for a group of nations placed between Russia, China, Europe, and the Middle East.

And just like Europe’s depopulation trends, population growth will also require smart policy foresight, planning, and ultimately seismic geopolitical, economic, and social shifts.

—

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.