Slovenia takes over the EU presidency at a crucial time, with the bloc facing significant problems including Covid-19 and a stalled enlargement process that risks leaving the Western Balkans states out in the cold.

Slovenia replaces Portugal at the helm of the Council of European Union on July 1, and the country’s foreign affairs minister, Anže Logar, has been outlining the priorities and objectives of the Slovenian presidency.

“The presidency is an opportunity to strengthen integration within the EU and within its institutions, and to steer development towards an innovative and creative community based on sustainable development,” says Logar.

- Imitating Russia, Hungary bans ‘gay’ content – and that includes rainbow flags

- Fudan Budapest is not the answer to Hungary’s higher education needs

- Five inspiring Roma figures from emerging Europe

According to Logar, the Slovenian presidency will focus on four priorities — Covid-19 recovery and resilience, the future of Europe, strengthening the rule of law, and increasing security and stability in the European neighbourhood.

The presidency’s programme wants to build a European health union and support establishment of a health emergency preparedness and response authority, which aims to improve Europe’s capacity and readiness to respond to cross border health threats and emergencies such as Covid-19.

With so much public life and work having moved online in the wake of the pandemic, the presidency will also focus efforts on upping European cyber resilience, while the implementation of the Next Generation EU recovery plan and the accompanying Recovery and Resilience Facility will be priorities for the presidency in order to accelerate the green and digital transition in the European Union.

Slovenia’s presidency also coincides with the Conference on the Future of Europe, a citizen-led series of debates and discussions that will enable people from across Europe to share their ideas and help shape future policy. As EU Council president, Slovenia will be co-chairing the conference.

“We will invest our efforts in promoting debate on the kind of Europe we want to live in,” says Logar.

Restarting the Western Balkans accession process

Covid-19 aside, the issue that looms largest in the Slovenian presidency’s inbox is the stalled accession process of the Western Balkans states.

One of the key events of the presidency will be the next EU-Western Balkans Summit, scheduled for the autumn.

The process of enlarging the EU in the Western Balkans has ground to halt over the past 18 months, most notably in the case of North Macedonia, with Bulgaria continuing to veto the beginning of accession talks with the country because of a dispute over mainly cultural issues, including the Macedonian language, which Bulgaria wants recognised as a dialect of Bulgarian and not a language in its own right.

With North Macedonia’s EU accession coupled with that of Albania, Bulgaria has effectively been blocking both countries from beginning talks. Slovenia will be keen to end the stand-off without having to decouple Albania from North Macedonia, something which most analysts believe would be counterproductive, as it could increase antipathy to the EU throughout the region.

Serbia’s EU accession also needs to be given a kick start. Once the region’s frontrunner, the country did not manage to open a single new negotiation chapter in 2020.

“The European future of the Western Balkan countries and the continuation of the enlargement process must become the Union’s strategic interest,” says Logar.

“Our roadmap is focused on socio-economic recovery and the integration of the Western Balkans into different European policy areas, ranging from infrastructure, transport and energy connectivity to research and innovation, decarbonisation, digitalisation and cyber resilience.”

Marshall Twito

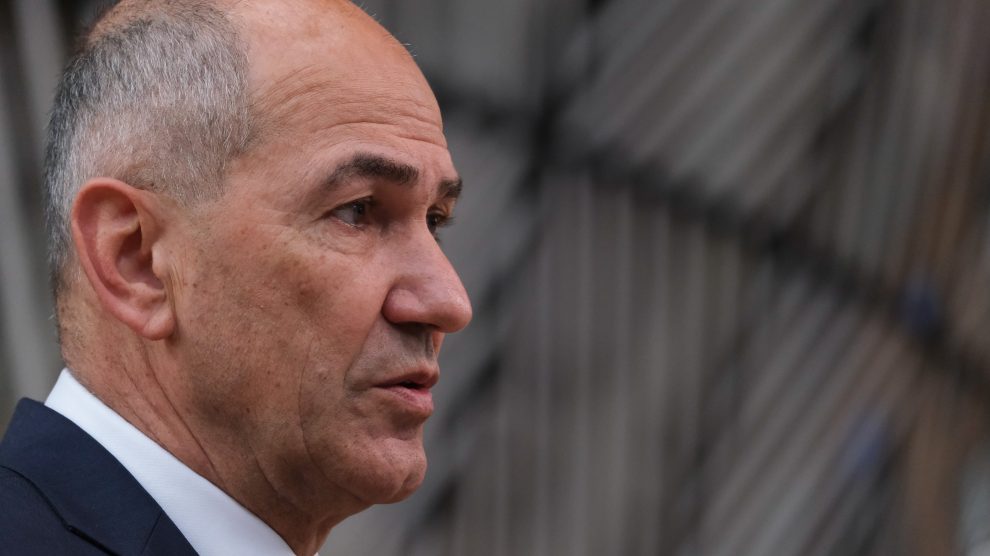

Slovenia will take over the presidency under the leadership of Prime Minister Janez Janša, a right wing politician and close friend of Hungary’s Viktor Orbán. Slovenia’s Hungary-like turn in recent months has seen increased pressure on media casts doubts on the country’s credibility as a European leader.

In May, Janša survived an impeachment motion filed by four opposition parties, accusing him of mismanaging the Covid-19 pandemic, failing to order enough vaccines, and attacking the media, most notably the state-funded news agency STA.

In February, the the Slovenian government’s communication office suspended payment to STA, which many in the country have seen as an attack on the editorial independence of the agency.

Janša has earnt himself the nickname ‘Marshall Twito’ for the way in which he makes use of the social media platform Twitter to attack opponents and make baseless claims.

Last month, Janša used Twitter accused the STA’s director, Bojan Veselinovič, of collaborating in the “murder” of a former STA editor-in-chief, Borut Meško. Meško died of cancer in 2010.

According to the New York Times, with Donald Trump now banned from Twitter, Jansa has taken his place, albeit with far fewer followers, in setting the benchmark for intemperate social media messaging by a national leader.

Europe could be in for a lively six months.

Photo: Janez Janša (Council of the European Union).

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.