If Belarus is to maintain its sovereignty, then dismantling the Lukashenko dictatorship is critical.

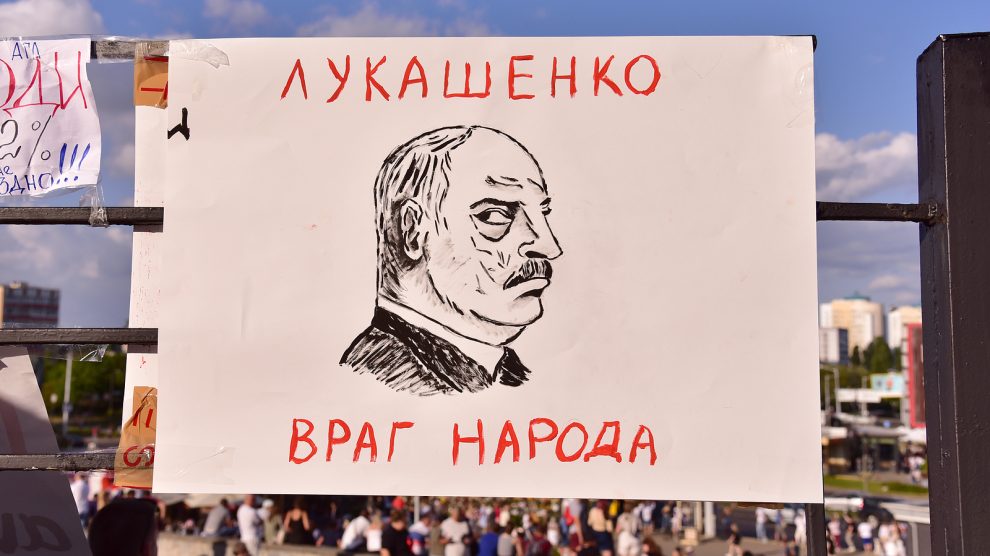

Among Eastern European states, none have remained under Russia’s influence the way Belarus has. Its president, Alexander Lukashenko, a self-described dictator, has ruled the country with an iron fist since taking office in 1994. As such, it comes as a surprise to many that after one year of war, the Belarusian military has yet to join Russia’s war on Ukraine.

- The sports community should not reward Russia

- On human rights, emerging Europe remains a divided region

- For most of Central and Eastern Europe, 2023 will likely see a slowdown in growth

Ever since Lukashenko’s illegitimate re-election in 2020 and the massive anti-government protests that followed, his hold on power has been tenuous. While Russian intervention was able to quell the protests, the regime lost much of its credibility.

No favour goes unpaid, however, as the protests were an opportune moment for the Kremlin to further assert itself in Belarus’ internal affairs. According to a leak in February 2023, Russia seeks to gradually dismantle Belarus’ statehood throughout the course of the next decade.

Belarusian civil society – both within and outside the country – has mounted pressure on the regime to remain neutral. Now, with discontent still brewing at home, Lukashenko finds himself walking a tightrope as he struggles to ensure his regime’s stability while being beholden to Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Homegrown opposition

The tumultuous elections in 2020 were a turning point for Belarusian society. Up until that point, the Lukashenko regime may have held some semblance of legitimacy. The blatant disregard for democratic norms, however, as well as the work done by opposition leader Svetlana Tikhanovskaya dispelled any illusions that may have remained.

While Lukashenko remained in power, the elections are widely considered to be illegitimate and Tikhanovskaya continues to lead the Belarusian opposition in exile. In August 2020, she and other opposition figures founded the Coordination Council which has been seeking the democratisation of the country. This has naturally created a problem for Lukashenko as the Coordination Council has emerged as a viable alternative to his rule – a major development in the past 30 years.

Instability within the country continues as well. Belarus serves as a staging ground for Russian operations in Ukraine. From the very start of the war, Belarusian activists have been actively involved in logistical sabotage while volunteers fight for the Ukrainian military.

Belarusian railways, which formed part of Russia’s logistical network, have been a key target. According to Oleksiy Arestovich, strategic communications adviser to the office of the president of Ukraine, its sabotage “made life difficult for the Russian troops”. In late February 2023, Belarusian partisans managed to use drones to damage a Russian surveillance aircraft stationed near Minsk.

In order to control the situation, Lukashenko has turned to increasingly authoritarian measures. In early March 2023, Nobel Peace Prize winner Ales Bialiatski was sentenced to 10 years in prison. This was followed by a 15-year court sentence for Tikhanovskaya in absentia and the extension of the death penalty to include acts of high treason. Tikhanovskaya described the move as Lukashenko “trying his usual tactics of intimidation”.

The possibility of direct military involvement remains low, however. A survey by Chatham House concluded that 93 per cent of Belarusians are against military engagement. Lukashenko needs the army’s protection to maintain power in Minsk. Deploying them to Ukraine would turn the country against him. With an approval rating below 30 per cent and a preoccupied Russia, this is not a risk Lukashenko can afford to take.

Independence on the line

Lukashenko has made numerous diplomatic moves to ensure his political viability. In January, he stated Belarus would not attack unless provoked, sparking a Ukrainian proposal of a non-aggression pact. In February, Lukashenko visited Beijing where he reiterated the country’s commitment to “efforts to restore regional peace and order” with Chinese President Xi Jinping – another strenuous Putin ally. In March, Belarus also vowed together with Iran to increase cooperation with Russia.

The delicate balancing act is not without risk. Russia has long sought to incorporate Belarus through the Union State. As was revealed in a leaked document in February, the Kremlin intends to increase this dependence in the coming years.

Hanna Liubakova, a non-resident fellow at the Atlantic Council says that the document has exposed Russia’s strategy to occupy and colonise Belarus.

“I’d argue that many of the steps in that document have already been implemented, such as the complete control of political life, the economy, and media in Belarus. This is a hybrid occupation and it has been taking place for years,” she tells Emerging Europe.

“Since 2020, integration processes intensified. Currently, we can state that Belarus lost its sovereignty in the military, economic, foreign policy and information spheres. Lukashenko is not left with many options and tools to refuse if Putin would demand further concessions, for example, the deployment of Belarusian troops to Ukraine,” she adds.

Nevertheless, Liubakova stresses that “Belarusians firmly oppose the war and this participation has not been discussed and/or approved by people.”

“Despite propaganda and censorship, people increasingly understand that Belarus must leave the so-called ‘Union State with Russia’ and the Collective Security Treaty Organisation as soon as possible. These organisations keep Belarus in the Russian orbit, they also threaten Belarusian independence and would only be slowing down any reform process unless abandoned.”

Little of this is likely as long as Lukashenko remains in office. According to Liubakova, if Belarus is to maintain its sovereignty, then “dismantling the dictatorship of Lukashenko’s regime is critical”.

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.

Add Comment