The amount of forested areas in Poland has been rising steadily over the past few decades. So why are forestry experts sounding the alarm?

Nearly 30 per cent of Poland, around 9.1 million hectares, is now covered with forests, up from 21 per cent in 1945. The vast majority of that area is managed by State Forests, a governmental organisation which comes under regular fire from scientists and pro-nature activists.

- Report urges Poland to embrace renewables, not gas

- Poland and Czechia strike deal over Turów coal mine, leaving locals unhappy

- Fit for 55: Poland’s stalling casts dark cloud over EU’s climate goals

Critics accuse State Forests of ill-advised logging of old-growth forests, most recently in the Białowieża Forest on the border between Poland and Belarus.

One of the largest remaining parts of the primeval forest which once stretched across the European plain, the Białowieża Forest last year suddenly found itself on the receiving end of Europe’s most recent migrant crisis.

When thousands of people from the Middle East and Africa tried to enter the European Union via Belarus last summer, the Polish authorities decided to stem the tide by building a 186 kilometre wall along the border.

The 2.7 kilometre section which will cut through the strict reserve of the Białowieża Forest may not seem as much at first glance, but scientists say it will have a disastrous effect on local wildlife.

While it is disputable whether the barrier will have any real bearing on the migrant crisis, which has since abated, it will certainly disrupt migration patterns of local bison, wolves, lynxes and other endangered species, putting the genetic health of these populations in even greater jeopardy.

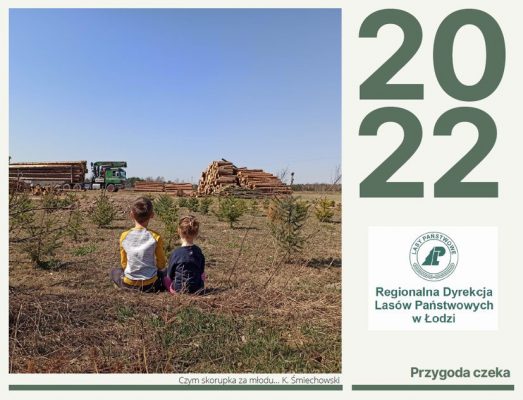

In another head-scratching moment, the Regional Directorate of State Forests in Łódź recently published a calendar, the cover of which clearly defeats the very purpose of the institution. In the photo, two children are seen looking at freshly-cut trees, while the caption beneath reads: What youth is used to, age remembers.

Tree plantations

According to official data, Poland produces around 40 million cubic metres of timber every year, which typically requires the felling of around 40 million trees.

While these figures have more than doubled since 1990, the total area of forests in the country has been growing over the years nonetheless. As many as 500 million saplings are planted each year, or an impressive average of 1,000 trees every minute.

And yet, according to Michał Żmihorski, head of the Mammal Research Institute of the Polish Academy of Sciences, maths alone does not come close to explaining the true nature of the ongoing change.

“What we need to remember here is the difference between a forest and a plantation,” Żmihorski tells Emerging Europe. “In my opinion, a large proportion of forests planted in Poland these days are indeed nothing else than tree plantations, and I also know that many biologists and foresters agree with me on this.”

“There’s an empty field somewhere, a tractor arrives and ploughs the field. Saplings are planted in rows and sprayed with pesticides, and oftentimes such places are even fenced. That’s a classic example of a plantation,” Żmihorski adds.

Krzysztof Cibor, biodiversity expert at Greenpeace Poland, says that State Forests are clearly focused on timber sales figures rather than on any greater good.

“It’s high time authorities understood the need for a major shift in how Polish forests are managed,” Cibor tells us. “The way we treat nature and produce timber ought to change drastically. Sure, we do need timber, but we have to log trees in a much smarter, selective way.”

“Logging needs to move away from large areas such as the Białowieża Forest or the Noteć Forest. At least 15 per cent of Polish forests should permanently be excluded from our long-term logging strategies,” Cibor continues.

Can’t see the wood for the trees

According to Rafał Szefler, head of the Polish Economic Chamber of Wood Industry, the core of the problem is that there is no long-term thinking.

“State Forests say they do have a strategy, but then they also change it very often,” Szefler says.

“I once came across a wonderful publication which detailed how Polish forests could be restructured within the next 50 years. For instance, it showed how we could decrease the dominance of pine trees in our forests,” Szefler says. “Sadly, such ideas somehow always end up being shelved.”

Michał Żmihorski of the Mammal Research Institute of the Polish Academy of Sciences says that at the end of the day it’s all about setting the right priorities.

“The question we need to answer is what primary function we would like our forests to serve. Is it timber production, nature conservation, or tourism? If a given forest is located close to a big city, then surely the recreational value of such a forest is much greater than production of boards,” Żmihorski says.

“We might as well take [Kraków’s] Wawel Royal Castle to pieces and use the bricks to build something else. And yet, somehow we all agree that the reason we maintain the castle in a good shape is altogether quite different,” Żmihorski concludes.

State Forests has been approached several times for comment about its long-term strategy but the organisation has not responded.

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.