Consumer electronics were rarely a top priority for most of the countries of Eastern Europe before 1989. Bulgaria’s Pravetz 82, a pioneering home computer, was an exception.

Bulgaria’s economy at the end of the 1970s was in a sorry state, facing many of the same challenges that plagued all of the planned economies of Eastern Europe at the time.

Not the least of these was attempting to deal with the fallout from massive and yet poorly managed investment in heavy industry during the early 1950s. This investment had left the country with machinery that was already out of date but far too expensive to upgrade or replace, making much of its heavy industry uncompetitive.

- History and tax incentives: Why Bulgaria and Romania lead the way on ICT gender equality

- Why Ukraine currently leads the race to develop a digital currency

- Christo’s ‘L’Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped’ and his complicated relationship with Bulgaria

And yet there was one small sector of the Bulgarian economy that was (at least relatively) in good shape: its technology sector. Bulgarian factories were already producing various computer components and peripherals such as hard drives by the end of the decade.

Rosen Plevneliev, a former Bulgarian president and honorary chairman of the Tech Emerging Europe Advocates (TEEA) advisory board, witnessed the development of the country’s tech sector.

“Bulgaria specialised in computer science and software, and at the beginning of the 1980s, the country was among the world’s top five exporters of computer components,” he tells Emerging Europe.

The IMKO-1

Bulgaria’s communist government increasingly looked to computers to revitalise the wider economy, believing that they could usher in a new era for communism, one where mundane tasks could be automated and workers truly liberated.

To its credit, communist Bulgaria got a lot right. It started educating a new generation of young people to work with computers, and as the 1980s began and the global computer industry pivoted towards personal computers, Bulgaria followed suit.

“More than 60 science and technology institutes, universities, and factories were created as a part of the national IT ecosystem,” says Plevneliev. “As a result, the first 8-bit, 16-bit, and 32-bit computers, graphic stations, memory storage facilities were all designed and created just months after the equivalent western products.”

The development of the first Bulgarian personal computer, dubbed IMKO-1 (from individual microcomputer), began in 1979 at the Institute for Technical Cybernetics and Robotics.

Around 50 units were produced for testing purposes. Technically, the IMKO-1 was a reverse engineered clone of the Apple II Plus personal computer, with some changes such as the ability to display Cyrillic fonts.

IMKO-1 boasted a one megahertz CPU, a whole 48 kilobytes of memory and a cassette player port intended for storage.

The computer beat out its western counterparts in one key area — it could control of a robotic arm, ROBKO-1.

At the time, robotic parts were usually controlled with larger and more expensive minicomputers rather than a microcomputer such as the IMKO-1.

The Pravetz 82

Essentially, the IMKO-1 was a prototype of what would become the Pravetz 82.

Starting life as the IMKO-2, the name was changed to reflect its origins — a new computer factory in the western Bulgarian town of Pravetz, also the hometown of longtime Bulgarian Communist party leader Todor Zhivkov.

Zhivkov was himself was a strong supporter of Bulgaria’s plans to become a computer production powerhouse: he once said that the country should become “the Japan of the Balkans”.

Introduced in 1982, the Pravetz 82 featured several improvements over is predecessor, including the addition of an optional 5.25 inch floppy disk drive for storage.

But even through the Pravetz 82 was nominally a personal computer, few in Bulgaria could actually afford one for their own personal use.

Instead, most made their first forays into computing in schools, which the government supplied with thousands of Pravetz 82 units.

Soon, computer clubs started sprouting up across the country, where young people tinkered with various programmes and robotics parts.

At the same time as the UK hobbyist video game scene was heating up (on home computers such as the ZX Spectrum and the Commodore 64), in Bulgaria young people were increasingly assisting institutions with homegrown computer programmes doing everything from graphic design to managing the booking of hotel rooms.

Big in COMECON

The Pravetz 82 also made its mark abroad. At the peak of the Bulgarian computer hardware industry towards the end of the 1980s, it was supplying around 40 per cent of all computers found in COMECON countries.

Ultimately, the techno-utopia that Zhivkov and the rest of the Communist party envisaged did not come to pass.

Once Bulgaria abandoned communism and central planning, and opened its markets, it could no longer manufacture and sell its computers that were often based on the outright pilfering of western designs.

But it would be wrong to say that it was all for naught. Once the economy was liberalised, some of the first private companies in the country were computer firms, owned and operated by those very same kids who tinkered with Pravets units at school.

A number of them left for Silicon Valley, bringing with them STEM expertise and the spirit of techno-utopianism, albeit in a new fiercely individual and liberal form.

And as Bulgaria found its footing in the new globalised economy, it again emerged as a regional leader in the ICT sector with a start-up ecosystem that is continually advancing and developing.

“It is logical that in recent years Bulgaria has managed to further develop its strong potential from the past by creating a thriving and broad IT ecosystem spreading from the gaming industry, through big data, AI, and all aspects of software engineering,” adds Plevneliev.

Is it all thanks to the Pravetz 82?

No. But the availability of the computer and the introduction to programming it offered created a generation of Bulgarians familiar with computers, keen to build their own version of Japan in the Balkans.

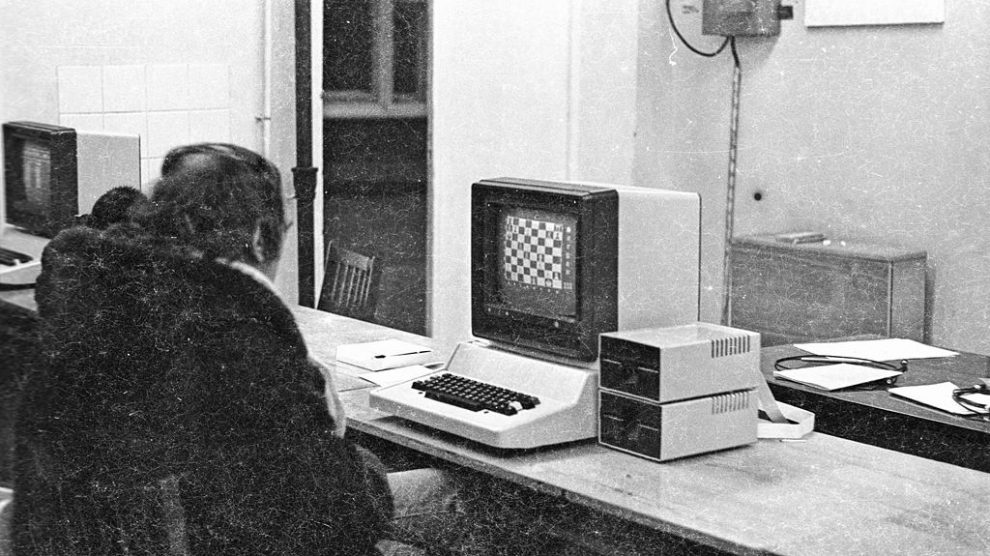

Photo: Chess on a Pravetz 82. Pereslavl Week/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.

Add Comment