The frustratingly slow process of integration with the European Union has Ukraine looking for alternative partners.

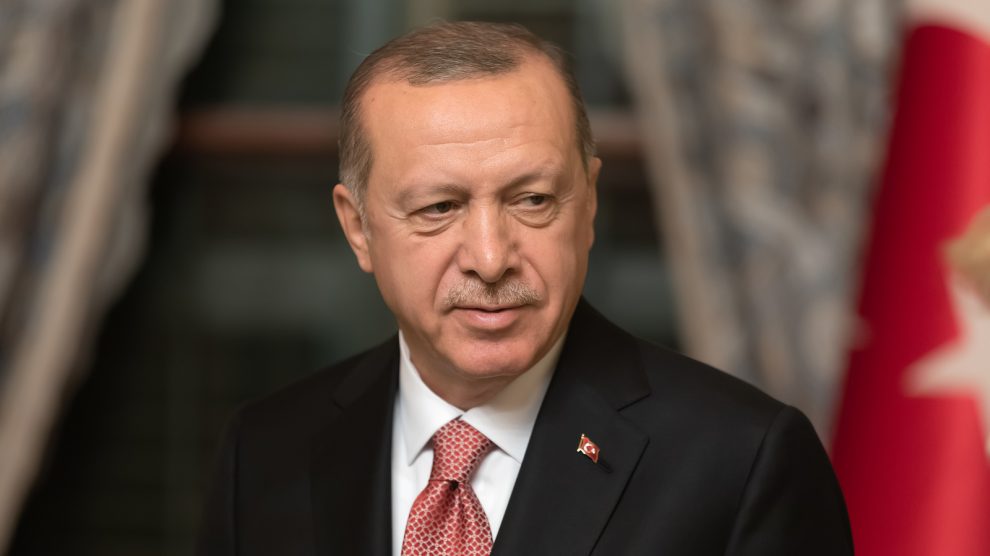

In April, at the height of the border standoff between Russia and Ukraine, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky met with his Turkish counterpart Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

- What next for the EU’s Eastern Partnership?

- New hope for Ukraine’s iconic aircraft manufacturer Antonov

- New EU-Ukraine raw materials partnership puts ESG front and centre

Erdogan was unusually outspoken: he reiterated Turkey’s support for Ukraine’s territorial integrity, reaffirmed his country’s backing of Ukraine’s NATO membership bid, and promised to enhance military and economic cooperation.

Prior to 2014, Ukraine and Turkey had few relations beyond trade and tourism. However, the Russian annexation of Crimea created a new problem for Turkey: all of a sudden, the balance of power in the Black Sea shifted. Russia significantly expanded its territorial waters on the Black Sea. It subsequently cancelled agreements with Ukraine which limited the size of the Black Sea Fleet and began rearming the Sevastopol-based fleet.

For Kyiv, the benefits of a tighter relationship with Turkey are obvious. Turkey is a geopolitical rival of Russia – the two have found themselves supporting opposite sides in Syria, Libya and the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh. Turkey has NATO’s second largest and arguably second most powerful military, with a burgeoning domestic military industrial complex.

Furthermore, Ukrainians are growing increasingly frustrated by the lack of progress made on integration with the European Union. Some commentators complain that Ukraine is treated as a nuisance rather than a partner and prospective member. Multiple times, Ukraine’s western allies – the United States in particular – have (successfully or otherwise) tried to strong arm Ukraine into doing their bidding. The prospect of membership today seems to be as distant (or even more so) than it was in 2014.

This pushes Ukraine into the arms of Turkey, another (former) EU aspirant that was regularly given the cold shoulder by Brussels.

Defence co-operation

Ukraine and Turkey’s growing partnership is most evident in the defence industry.

Since 2014, the two countries have signed three different agreements cementing their military cooperation. In 2018, Ukraine acquired six Bayraktar TB2 drones – the crown jewel of Turkey’s defence industry, with plans made to acquire up to 48 more. The Akinci drone, deliveries of which to the Turkish military began this year, uses a Ukrainian-made engine.

Discussions have also been held about jointly producing corvettes and the AN-178 military transport aircraft. Turkey’s brand-new Atmaca anti-ship cruise missile, with a 200-kilometre range, also uses a Ukrainian-built engine, and the Ukrainian Navy has already made plans to acquire them.

Cooperation also extends beyond the military sphere. Roughly 1.6 million Ukrainians visit Turkey every year, making it one of the country’s favourite tourist destinations. Turkish investments in Ukraine currently exceed 500 million US dollars, a 30 per cent increase compared to 2014. Bilateral trade between the countries is valued at five billion US dollars – at April’s Ankara summit, Ukraine and Turkey’s ministers of trade set a goal of doubling this value.

However, Turkey’s inconsistent relationship with the Kremlin has to be kept in mind – despite being on opposing sides in many issues, the two countries still cooperate, as evidenced by Russia’s sale of its advanced S400 missile system.

Despite this, Turkey has undoubtedly done more for Ukraine (at least in the military field) than any other single NATO member – the links that the two countries have built in their defence industries will significantly bolster the effectiveness of the Ukrainian military and have long-term benefits, in a way small shipments of American-made Javelin anti-tank missiles won’t.

With both countries having clear, complementary advantages in cooperation, we may yet see them become more intertwined in the coming years.

Ukraine’s plight since 2014 has also seen it extend its arms to countries even further away, like China, particularly since Zelensky’s election. This has been significantly more controversial with Ukraine’s western allies (particularly the United States), worried about China’s increasing influence on the world stage.

This was typified earlier this year in the fracas around Motor Sich, a Zaporizhia-based producer of engines for airplanes, helicopters and missiles. Ukrainian authorities, apparently under pressure from the United States, blocked the takeover of the company by Chinese state-owned aviation firm Skyrizon.

It was speculated that the Americans were concerned about China getting access to sensitive jet manufacturing technology to support its relatively underdeveloped aviation industry. The Ukrainian government subsequently sanctioned four Chinese enterprises and three Chinese individuals involved in the attempted deal.

Beijing’s reaction was moderate, however – China simply applied for international arbitration. This implies that Beijing is relatively relaxed about its prospects within Ukraine – and for good reason.

Stepping into the vacuum

The outbreak of war in Ukraine in 2014 and the occupation of Crimea severely damaged trade with Russia, then Ukraine’s biggest trading partner. Association agreements with the European Union could not sufficiently make up the deficit – so China stepped into the vacuum. Between 2019 and 2020 alone, Ukrainian exports to China grew by a whopping 98 per cent, to 7.1 billion US dollars – this is largely driven by iron ore, grain, and iron and steel. The same year, imports from China totalled 8.3 billion US dollars.

Rather than allowing the controversy around Motor Sich to jeopardise its ties with Kyiv, China has pressed ahead with its charm offensive. On June 25, Ukraine withdrew its signature from a joint statement of mostly western nations condemning China’s actions in its Xinjiang province.

Less than a week later, on June 30, Ukraine and China signed an agreement strengthening cooperation in the infrastructure sector. According to the agreement, Ukraine can receive Chinese loans at preferential rates for the construction of large-scale infrastructure projects – if implemented, this would be a long-overdue and much-needed initiative.

On July 1, to much domestic controversy from pro-western politicians, Volodymyr Zelensky congratulated the Chinese Communist party (CCP) on the 100 year anniversary of its founding. Ukrainian parliamentarian and Zelensky affiliate Davyd Arakhmaia subsequently gave an interview with Chinese state media praising the CCP for its accomplishments and stressing the similarities in economic strategies between the two parties.

With Ukraine frustrated at the lack of support it has received from the western allies it has been courting, it is now looking for alternatives. The completion of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline – likely later this year – will make the European Union even more dependent on Russia, further compromising Ukraine’s security – and the United States still yet to offer a fraction of the military support Turkey has.

This may be an indication that Ukraine is no longer trying to “put all its eggs in one basket”.

Ukraine’s independent history is replete with governments validating a false binary between being “pro-Russian” and “pro-European”, each time alienating one or the other.

Pursuing a more independent policy – which both leverages Ukraine’s strategic geographic position between Russia and the EU, and simultaneously counterbalances these powerful influences with more distant, objective powers – can have the most long-lasting benefits for Ukraine.

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.

Add Comment