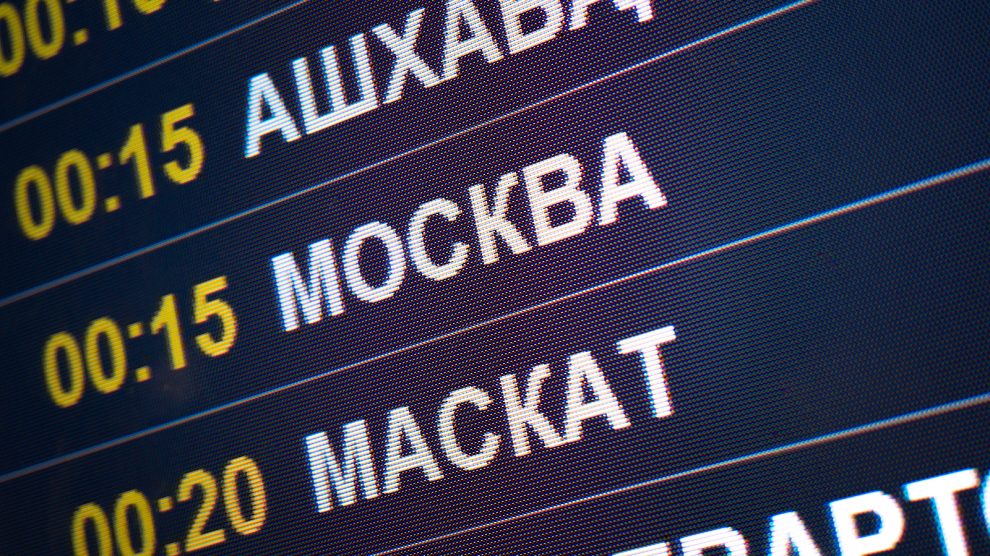

Russia’s economy has long relied on workers from Central Asia, but Covid-19 restrictions have halted seasonal migration, while millions of labourers already in Russia have been forced to return home.

For decades, large-scale migration from Central Asia to Russia has been a mutually beneficial arrangement: Russia reinforces its declining labour force while the the migrants’ home countries receive sizeable sums in remittances.

However, the Covid-19 pandemic and restrictions on travel have brought a halt to cross-border migrations, creating several knock-on effects in both Russia and Central Asia.

- As Turkmenistan’s economy sinks, its capital becomes world’s most expensive place to live

- Continuing to build ‘Fortress Europe’ would be a mistake: it’s time to manage migration, says new study

- To reduce urban-rural divide, Central Asia must embrace freedom of movement

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russia has consistently had one of the world’s largest immigrant populations, according to statistics from the International Migration Organisation.

In 2019, shortly before the pandemic struck, Russia had over 10 million migrants – both legal and unregistered – living within its borders, the vast majority from the former Soviet republics of Central Asia. For the better part of the 21st century, around 10 per cent of Tajikistan’s entire population has been living in Russia.

On the surface, this arrangement has benefits for both Russia and for the countries the migrants come from. Russia’s population has been steadily declining or remaining stagnant for three decades, while every country in Central Asia has seen its population grow. This is particularly true for Uzbekistan, the most populous country in the region, which also has the highest rate of population growth.

With the Central Asian economies struggling to keep pace with their population growth, migration is seen as a viable release valve. It reduces the number of unemployed, and provides substantial income in the form of remittances, as wages are substantially higher in Russia. In 2019, over 30 per cent of Tajikistan’s GDP was composed of remittances, largely sent from Russia.

Dwindling numbers

However, according to recently-released figures from the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration, by April 2021, the number of migrants has dwindled to about 5.5 million – 42 per cent lower than the previous year. This follows border closures and expulsions of foreigners conducted by the Russian government in response to the Covid-19 pandemic – for much of 2020, the country was essentially paralysed and many migrant workers, unable to work and unable to pay their bills, returned to their home countries.

Russia has been one of the worst affected countries by the pandemic, with over 130,000 deaths recorded so far.

This has wreaked havoc on several Russian industries, particularly construction and agriculture, which rely on seasonal migrant labourers. According to Marat Khusnullin, Russia’s deputy prime minister for construction, the labour shortage in construction alone is estimated to be between 1.5 and two million people.

Employers have had to hike wages by as much as 50 per cent to attract more Russian workers. However, this has not been enough to fill the breach caused by the exodus of migrants.

This has come at a terrible time for Russia in particular. The country’s population has been in steady decline and last year was one of the costliest yet: the population shrank by 700,000, the biggest single-year fall since 2005.

The pace of Russia’s recovery from the Covid-19 induced recession will be limited as long as the labour shortage persists. Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov acknowledged this situation in April.

“We’re very, very short of these migrants to implement our ambitious plans. We have to build more than we are building now, but we need working hands to do it,” Peskov told state news agency TASS.

Economic strain

This is a particularly pressing issue in the face of Russia’s 400 billion US dollars national projects development package. The project, an ambitious public works programme, has already been pushed back to 2030 from an initial completion date of 2024, due to the pandemic. The labour shortages will cause further delays to the sweeping initiative. In April, the Russian government floated the idea of using convict labour.

The labour shortage has also badly affected many of the Central Asian countries. According to the World Bank, 2020 saw Central Asia’s first recession since the mid-1990s and Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have already appealed to international financial institutions for loans to mitigate the worst effects of the pandemic.

The region’s vaccination roll-out is slow, further hampering economic recovery.

The return of millions of working age people to their home countries has also put additional strain on the economies of Central Asia. With Russia still maintaining strict border controls, some workers are even starting to move to Kazakhstan. Kazakhstan has the region’s largest economy and offers higher wages than in the rest of Central Asia, albeit still lower than in Russia.

According to statistics from the respective governments, as of March 2021, there were over 400,000 citizens of Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan living in Kazakhstan, many of them workers who left Russia at the height of the pandemic.

With both Russia and the Central Asian states suffering economically, the current situation looks untenable.

Eventually, Russia will have to relax its border controls and welcome back the millions of workers it has lost over the past 18 months. It remains to be seen how many of those workers will be willing to return.

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.

Add Comment